AN UNEXPECTED HISTORY LESSON AT THE RIJKSMUSEUM

| October 27, 2014

The Rijksmuseum museum in Amsterdam has recently reopened after about 10 years of renovation. It’s a giant palace-like structure at one end of a park: the Museum Square as this park is known as, is also bordered by the Stedelijk Museum of contemporary art, the Van Gogh Museum and the Concertgebouw symphony hall. The Rijksmuseum in its present Amsterdam location was purposely built as a museum in 1885, but was commissioned in 1798 at an earlier site in The Hague, where the paintings were hung salon-style. The design was inspired by the Louvre, a former palace repurposed as a cultural monument to French-ness. Here there are stained glass windows celebrating classic artists and philosophers. It’s a big building for Amsterdam—and with its size, location and contents it makes a big statement.

Even centuries ago, the good people of Amsterdam were known throughout Europe for hanging pictures all over their houses. Of course the wealthy celebrated themselves and their endeavors in the work they hung and commissioned, but even middle class folks bought prints and cheaper paintings to hang. Pictures were a thing for Dutch citizens to have and cherish. Art was a way to enrich one’s life here—in ways it didn’t become for the non-elite in many other parts of the world until much later.

I had a morning off before a public discussion about music finances in the digital economy, so I biked over to see the collection and the renovated museum. I decided to start with the floor that covers the 1600’s, as that’s where they have their famous Rembrandts and Frans Hals paintings. Things are not arranged absolutely chronologically or by medium— some rooms of paintings were interrupted by a room of drinking vessels, for example. (The Dutch were also renowned as big boozers.) But there’s a rough chronology and thematic unity.

Early on in my walk-through, I saw a painting of a distant factory and a plantation in Olinda, Brazil. (Olinda is a charming colonial town next to Recife.) I didn’t even know that the Dutch had colonial business in Brazil, but they had muscled their way into areas all around the globe. The ruins of a previous colonialist’s building are prominent in the foreground of the painting.

Moving on, I saw a lot more paintings of Dutch settlements, plantations and trading outposts around the world. The reach of this now fairly modest nation—currently known for their quality of life, liberal views and open mindedness—was very impressive.

Here, painted in 1651 is the Dutch ambassador on his way to Isfahan, in present-day Iran (then known as Persia) making sure the two nations had acceptable trade agreements. The ships that would carry the goods to Holland are in the background.

Other than for the man with the turban, you wouldn’t know this painting was set in the Middle East. What would the contemporary equivalent of this celebration of a trade agreement be? A painting of Bill Clinton signing the NAFTA agreement with the Mexican president…with a row of recently built maquiladora factories in the background? Just saying. Trying to imagine contemporary equivalents—if any exist—often helps me understand what’s going on in a work like this one.

Here is a painting from 1661 of a fortress the Dutch built in Batavia (which is what the Dutch originally called Jakarta). This was where a lot of the business of the Dutch East India Company took place. In the bustling open-air market in the foreground, there are Chinese, Indonesians and others all engaged in the business of buying and selling. A mixed-race couple saunters in the foreground, while a servant fans them. Again I’m trying to imagine the equivalent: maybe a painting of the farmers market in Tribeca with the towers of Wall Street finance in the background. If any artist did that now it would be immediately viewed as an ironic commentary—this older painting is not ironic at all, as far as I can tell.

The Dutch business enterprise spanned the globe. Here is a trading post in Bengal (dated 1665). It looks like a fort, and maybe the similarity between a military and a trade endeavor is not accidental.

Closer to home, the prosperous Dutch had to invest heavily in protecting their many trading interests. For a long time they were at war with Spain—another vast colonial and trade power—that lasted for decades. In the galleries, the paintings of far-flung outposts that extracted goods from exotic lands were now interspersed with giant paintings of naval battles as Holland defended and extended its Mediterranean trade interests.

Here is a Spanish warship being blown to pieces—its crew flying into the air—near Gibraltar, painted in 1621. Gibraltar, being the narrow gateway to the Mediterranean, was a strategic prize. (The British control it now.)

In 1648, the Dutch and the Spanish signed a (temporary) peace treaty in Münster. (Isn’t that in Germany? Why was it signed there?) The momentous event that would facilitate renewed trade deserved to be celebrated.

The Dutch were busy. They were engaged in another trade war with the English. Here’s a painting of sea battle from the Anglo-Dutch war from around 1660.

The battles with the English ranged all over the Mediterranean. Here’s a 1660 painting of a battle near Livorno, a port in Italy. In British museums there are similar paintings, but in those the English are defeating the Dutch and burning their cities.

Securing ports and trade routes was critical to maintaining an empire’s power, particularly an empire that, being based in a relatively small country, was dependent on trade and sucking resources from far-flung outposts. Holland, like England and Spain, wasn’t a giant country with near “limitless” resources like China or India (or North America). To increase its wealth, it had to expand and dominate. It was becoming quickly obvious to me that these galleries of paintings were a celebration of that effort and the glorious home life it facilitated.

Here is a painting from 1669 of the local merchants who were getting rich off the goods manufactured from this trade. They had to be celebrated, too.

And the famous painting (1599) of the Drapers’ Guild with their mysterious gangsta hand signals:

The wardens of the drapers’ guild were the gatekeepers of the Dutch fabric industry: they approved the quality and types of wool and dyeing. A very powerful position, I would imagine.

I have to say that although the wall labels might have alerted us to the skills of these painters, it was the subjects of the paintings that were grabbing my attention. Rembrandt, for example, could paint in a myriad of styles, so he and his assistants could get—for a while—plenty of commissions for portraits, commemorative group portraits, religious works and landscapes. His skills as a painter were noted. There is also the stuff he seemed to do for himself: self-portraits and other work. Many of these are in a big new exhibition in London of late works. However, despite his skills, Rembrandt went broke: he was a compulsive buyer of art, antiques and props for his paintings and purchased a grand home shortly before a massive economic depression in Amsterdam, which meant creditors came calling. And tastes in paintings changed.

Back to the historical narrative. Needless to say, with all this trading and amassing of wealth, someone had to be assigned to guard it all. There were unsurprisingly a lot of paintings of militia groups—voluntary groups of (often wealthy) men whose job was to serve and protect the citizens of a district in case of attack, revolt or fire. This one from 1643 is a massive wall size panorama.

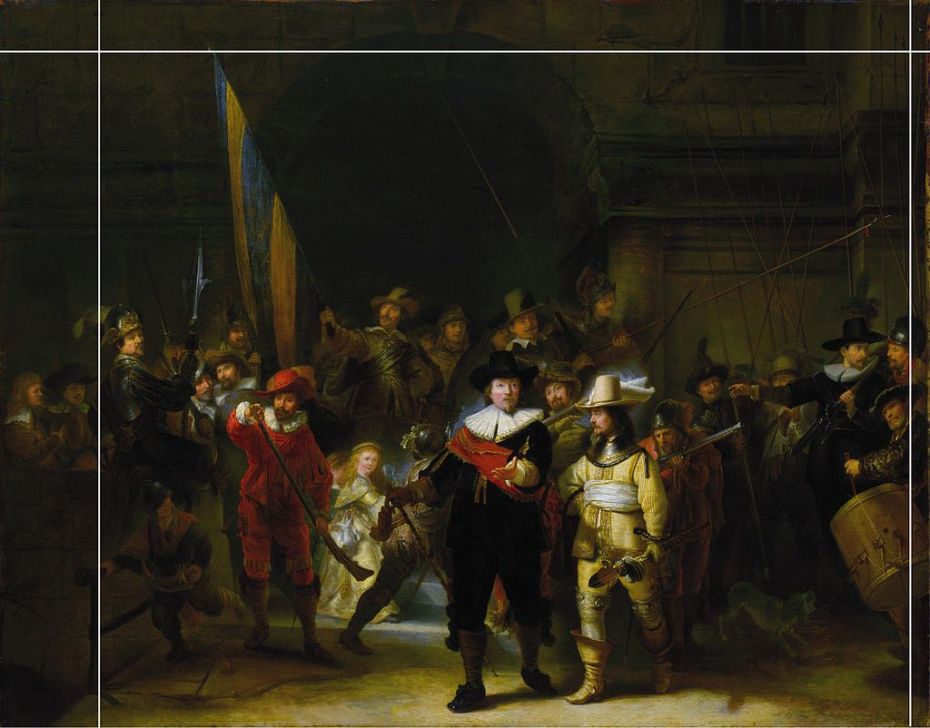

Rembrandt’s painting known as the Night Watch (1642) was originally called The Shooting Company of Captain Frans Banning Cocq and Lieutenant Willem van Ruytenburch preparing to march out. Commissioned by the militia group itself, it is now one of the most famous paintings in the world.

It was commissioned to hang in the musketeers’ meeting hall. One interpretation claims that it celebrates the uniting of the Dutch Catholics and Protestants in fighting off the Spaniards. (Usually the Catholics and Protestants were at odds. One amazing painting showed them on opposite sides of a river, fighting over the souls of the drowning.)

Despite its fame, what we see of Rembrandt’s painting now is not the original composition—or, one could argue, even the original painting. From Wikipedia:

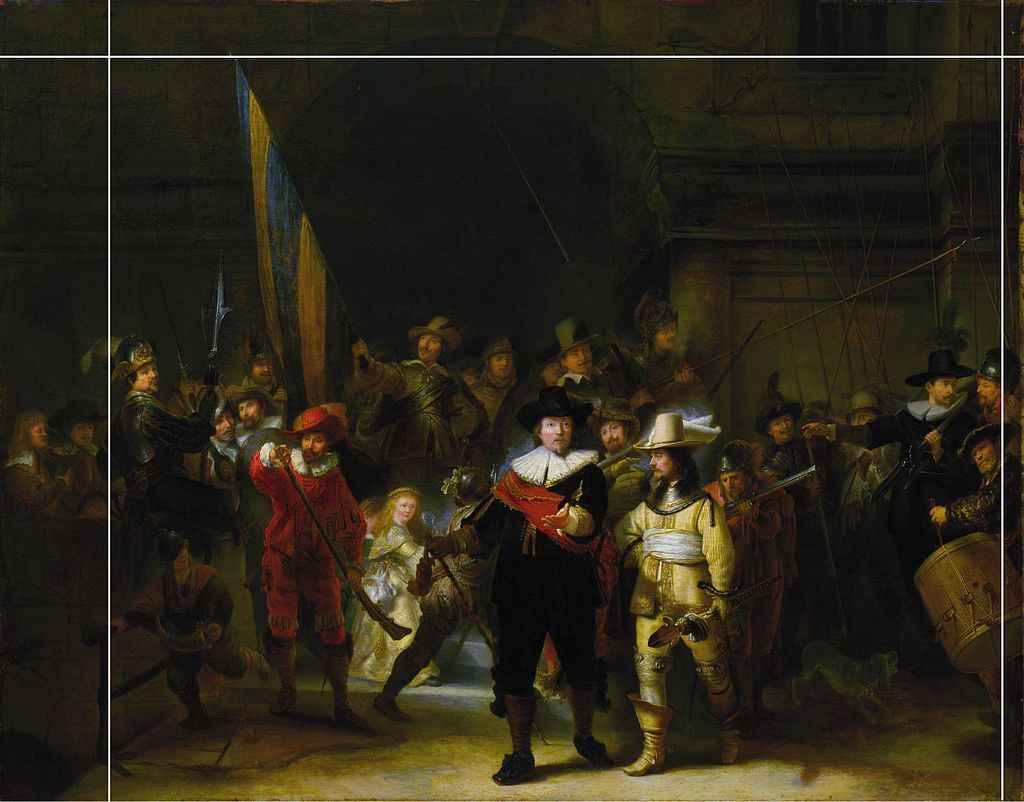

In 1715, upon its removal from the Kloveniersdoelen to the Amsterdam Town Hall, the painting was trimmed on all four sides. This was done, presumably, to fit the painting between two columns and was a common practice before the 19th century. This alteration resulted in the loss of two characters on the left side of the painting, the top of the arch, the balustrade, and the edge of the step. This balustrade and step were key visual tools used by Rembrandt to give the painting a forward motion.

The image above is of a copy made about 60 years after the original, by a different painter. This copy reveals that the trimming of Rembrandt’s original painting also managed to center the foreground figures—creating a more symmetrical composition than Rembrandt had intended.

Further on in the museum, in galleries focusing on later centuries, the visual legacy of colonialism and world trade continues. In one room, I saw a model of the Dutch settlement on a tiny Japanese island—essentially like the Bengal trading fort in the earlier painting, but this one was surrounded by water.

The Japanese were happy to enforce their cultural isolation, except that for two centuries they allowed this tiny island to exist as a trade port—and be their sole link to the larger world. A small bridge links the island to Nagasaki.

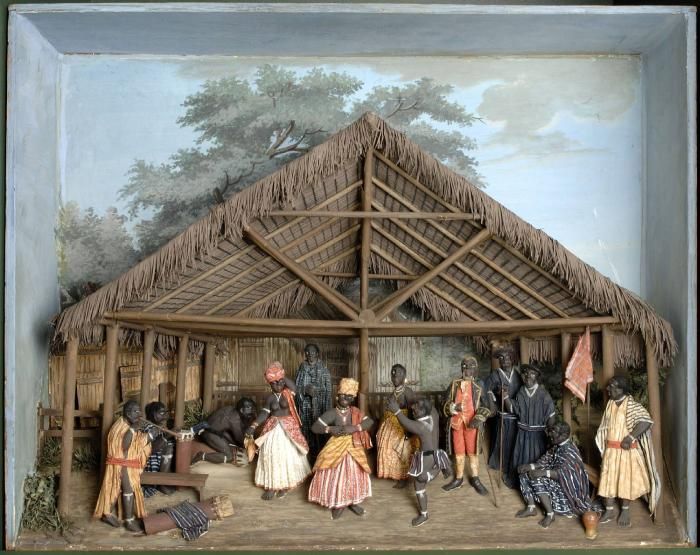

Nearby are some dioramas of dancing slaves in the Dutch plantations of Suriname. (Though Suriname is in South America, the workers were slaves imported from Africa.)

These dioramas were made by Gerrit Schouten, a government clerk, around 1820, and were to be sold as souvenir items.

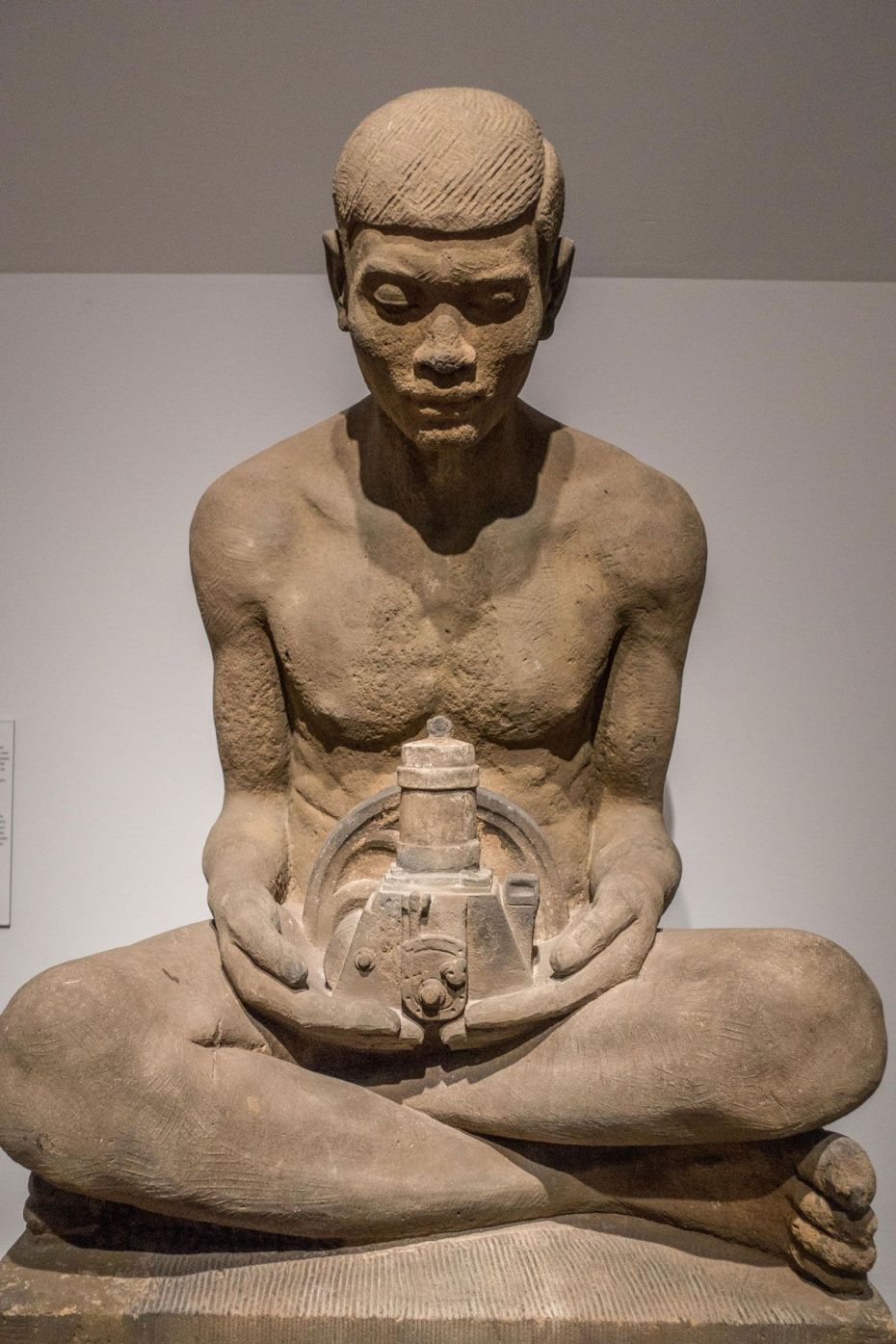

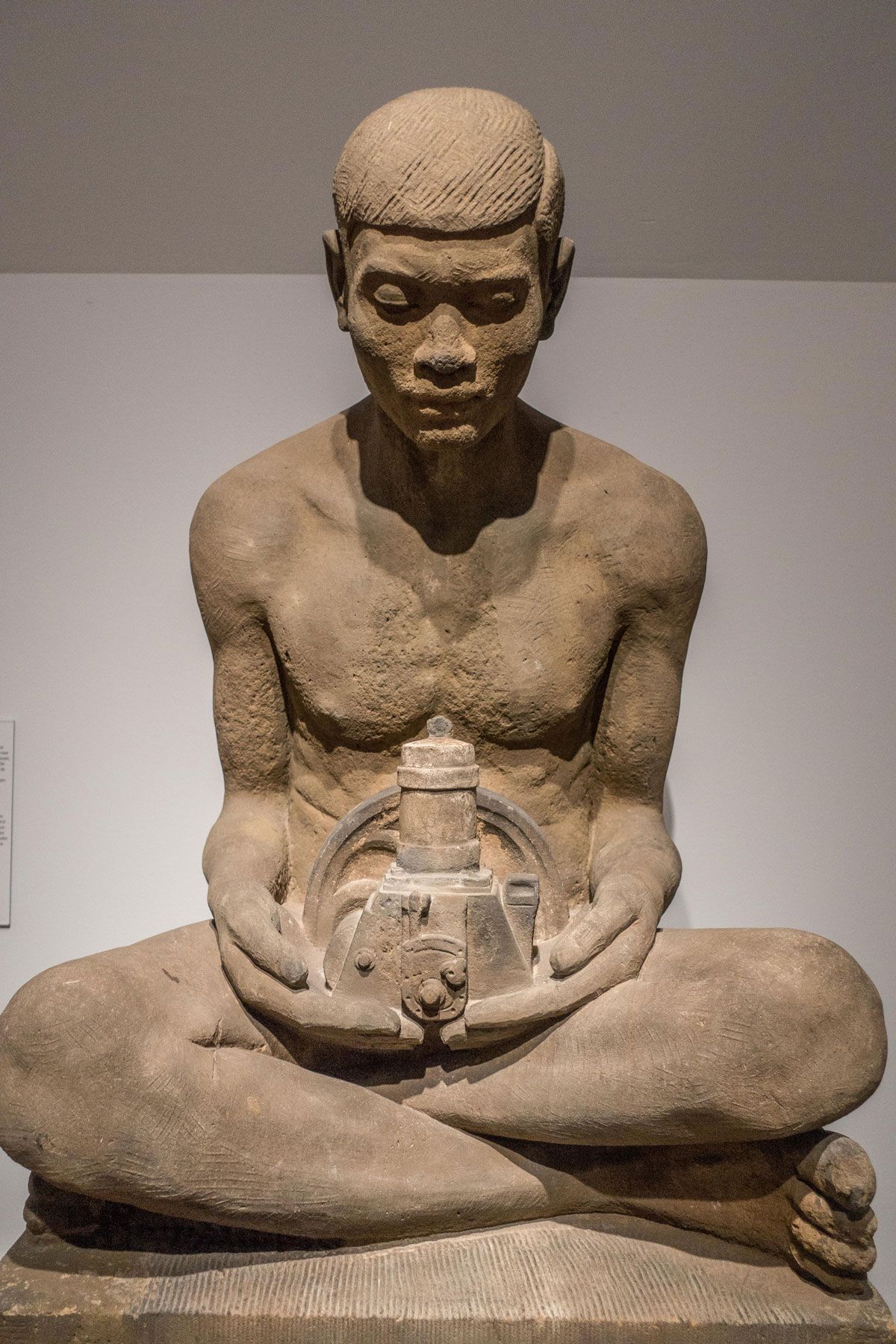

Here is a later item: a statue called Man and Machine from 1913 of an Indonesian man holding a miniature model of a large machine to be displayed by the factory office. The legacy of the Dutch East India Company was that the Dutch had Indonesia as a colony and a source of resources and manufacturing for centuries.

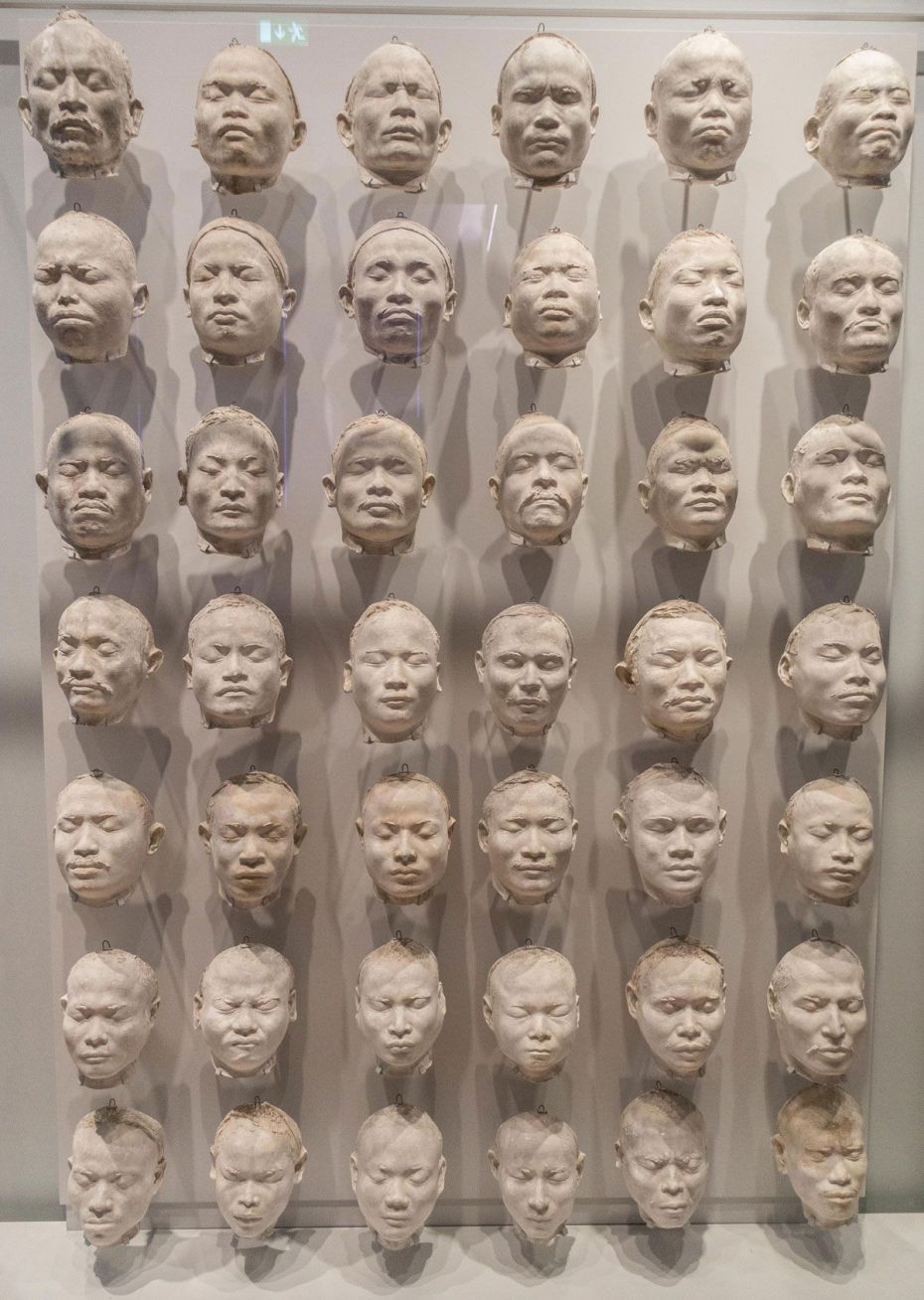

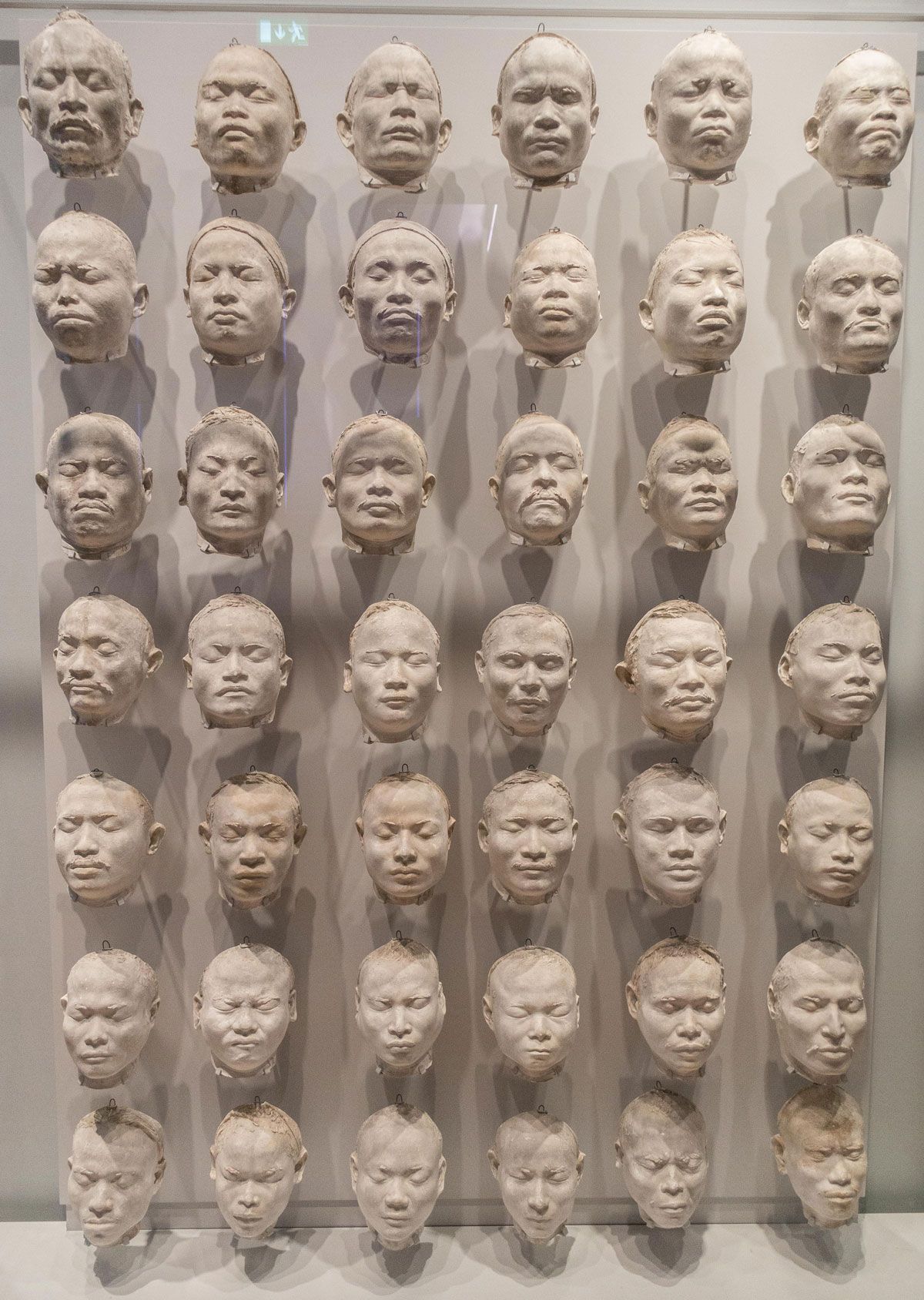

Anthropologists followed where industry led. Is knowledge thus gained via science a form of cultural capture—a form of ownership? Here is a wall of casts of the faces of Nias islanders from 1910. A beautiful, imposing and politically weighty visual. (Nias is a group of relatively small islands off the west coast of Sumatra, a part of Indonesia. The islanders have a unique culture as they have always been active traders but remained somewhat isolated on their island.

Anyway, my tour of the museum led me to view it as repository for incredible art and artifacts, but also as a giant monument and celebration of Holland’s Golden Age and its legacy: the colonial and trading settlements, the wars to maintain trade routes and hegemony and the businessmen and the militias who protected their interests. A celebration of an early version of globalization, with most of the glory going to the wealthy Dutch. As the Louvre is a celebration of French reach and culture, so is this a celebration of Dutch-ness.

Nothing wrong with a museum showing its nation’s history through the artwork of various epochs, but as often happens, the history and economics tends to get sidetracked, and safer discussions of the brushwork and the artists’ lives is given precedence. This seems a little disingenuous. Imagine an exhibit that included the imaginary NAFTA agreement painting described above, with a wall label that mentions the nimbus around Bill Clintons’ hair or the subtle positioning of his hand—and nothing about the actual complexities and consequences of the agreement.

The contemporary Dutch population reflects their colonial history, as happens everywhere. There are a lot of Indonesians in Holland…and honey-skinned folks who have clearly intermarried. These are the “new” Dutch. There are a lot of Muslims here as well, and Amsterdam has taken some unique steps to integrate and accommodate their immigrants, but there have been incidents. (The wonderful book Murder In Amsterdam gets into that situation.) Here is the window of a house in North Amsterdam—a former industrial and working class area that saw waves of immigration. (These are Javanese dancing dolls in the window, displayed to the street in front of European lace curtains.)

How do these immigrant folks who visit the museum react to seeing room after room of the triumphant Dutch dominating their former homelands…and the Dutch wealth that resulted? I suspect the school groups who visit might get more lessons about the artists than about the history. Maybe history and art appreciation would be separate classes in school.

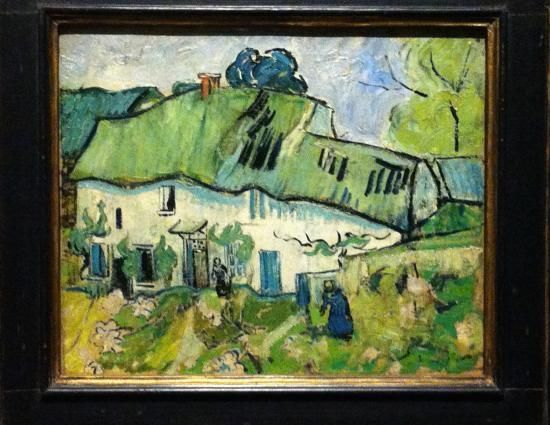

A little later comes what seems to be a break with this whole colonial time line—I entered galleries containing some Van Gogh’s, early Mondrians and paintings by some others who tended to paint mundane scenes, farm houses, and ordinary people as their subjects. Who would buy these? No one; not at the time.