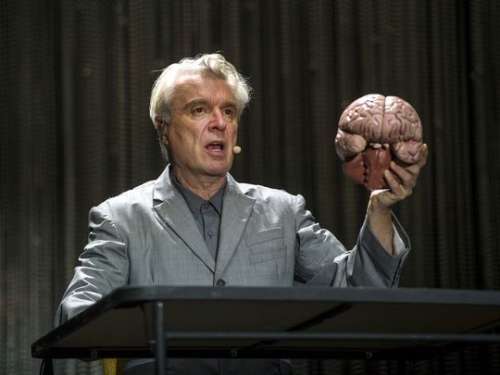

David Byrne brings a brain to the Beale Street Music Festival

By John Beifuss

Perhaps it’s appropriate that one of rock’s more cerebral performers would open his Beale Street Music Festival performance brandishing a human brain (or, to be precise, a prop facsimile of a human brain).

This “alas, poor Yorick” revamp, which adjusted the focus of contemplation from death to life, was not even the first sign that David Byrne’s 75-minute Saturday night set on the Bud Light Stage would be unlike anything festivalgoers had seen before.

The distinctiveness was evident even before the show began to anyone who noticed the stage had been transformed from a typical rock showcase into a stark box. Empty of amplifiers, wires, cables and even instruments (which would be introduced by the musicians, as needed), its three “sides” were constructed of metallic-seeming strings of beads that hung from the lights overhead to the floor below. The starkness was made to order for Byrne’s dramatic lighting effects, which – unlike those favored by most rock bands – were expressionistic, not pyrotechnic.

Photo: Brandon Dill / Special to The Commercial Appeal

On tour with a new album, “American Utopia,” but fated to be remembered by most as the erstwhile mastermind of the great rock band, Talking Heads, Byrne fulfilled the promise of the stage design, executing what was perhaps the most theatrical and certainly one of the more memorable shows ever seen in Tom Lee Park.

Dressed in a grayish suit a shade darker than his now silver hair (his bandmates were more or less identically attired), Byrne – making only his second Memphis appearance, after a 2008 show at the Orpheum – performed 16 numbers (seven of which were Talking Heads songs), backed by a precisely choreographed and entirely mobile ensemble of 11 musicians and vocalists, including six percussionists.

The mobility was a function of technology: The instruments were entirely wireless, allowing the players to remain untethered and fully a part of the choreography; this also eliminated “clutter” from the stage.

Secondarily, all instruments were portable; the keyboardist wore his electronic keyboard around his neck, while percussion was provided by a marching band-style drumline augmented by such rarely-seen-in-high-school noisemakers as an African talking drum; bongos; a shekere (a dried gourd covered in beads); and no fewer than three berimbau (a single-stringed instrument from Brazil).

Byrne, as usual, was a provocative, appealing ringmaster, his reedy voice suited to his unusual (for music) subject matter. Among other themes, the songs addressed technology – the very achievement that allowed Byrne's band its freedom – as a source of both hope and anxiety. The notion of community inspired similar caution: “Everybody’s coming to my house,” Byrne sang, as if in anticipation; then added, uneasily, “They’re never gonna go back home.”

Also as usual, Byrne’s rubbery physical presence provided a Chaplinesque commentary on the insecurity of life on this unstable planet. (For the Talking Heads classic “Once in a Lifetime,” he revived the electroshocked-puppet spasms of the famous Jonathan Demme concert film, “Stop Making Sense.”) Whether loose-limbed and goofy or regimented (at one point, the band formed a cross and rotated like a windmill), the choreography was always purposeful, even if Byrne sang: “If we could dance better/ You know that we would.” At one point, the musicians stumbled from one side of the stage to the other and back, like “Star Trek” TV actors when the camera tilts and the cast pretends to be tossed across the bridge of the Enterprise by an explosion.

Photo: Brandon Dill / Special to The Commercial Appeal

The set’s third song and first Talking Heads number was “I Zimbra,” composed of nonsense Dada lyrics; an hour later, the show all but concluded with the rousing Heads trifecta of “Blind,” “The Great Curve” and “Burning Down the House,” all ideally suited to the band’s percussion-heavy sound. However, the final song of the show was not a Byrne original but a cover.

Like the similarly dapper rock theorist, Tav Falco, who had inaugurated the same stage earlier Saturday, Byrne ended on a political note: He and the band, each with a percussion instrument, lined up side by side on the edge of the stage and faced the audience to perform Janell Monáe’s 2015 “Hell You Talmabout” (i.e., “What the hell are you talking about?”), which Byrne said had been updated, with Monáe’s blessing, because “sadly, it’s still as relevant now as it was then.” A protest of police violence, the song offers a tragic roll call of the names of the dead: Freddie Gray, Trayvon Martin, Sandra Bland, and on and on, until, finally, Emmett Till. It was a sobering, galvanizing conclusion to a transcendent evening.