David Byrne, Hammersmith Apollo, London — planned to perfection

Via Financial Times

Photo: Getty

By David Cheal

In his 2012 book How Music Works, David Byrne writes about how his experiences of performance and ritual in an Indonesian village transformed his way of staging live music. “I quickly absorbed that it was all right to make a show that didn’t pretend to be ‘natural’,” he writes. “The western . . . cult of spontaneity as a kind of authenticity was only one way of doing things on stage.” Out of this came an approach that put the emphasis on rehearsal, choreographed moves and repeated actions which he put into practice on his band Talking Heads’ Remain in Light tour in 1980. Far from being “unnatural”, Byrne writes, “ . . . each time it’s as real as it was the first time.”

Byrne’s American Utopia tour, which reached London this week, is the apotheosis of these ideas. It is choreographed (by Annie-B Parson of New York’s Big Dance Theater) to within an inch of its life. It is rehearsed, drilled, timed to the second. Every night the setlist is almost exactly the same (unlike those “spontaneous” rockers Pearl Jam, who have taken a repertoire of 50 songs on the road so that they can mix it up with each show). The lighting, the action, the music, the singing, the dancing, the movement: from start to finish, everything is planned. And from start to finish, it is joyous, life-affirming, pulsating, moving, thrilling, exhilarating.

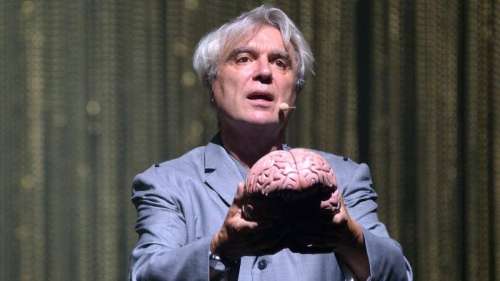

It began with Byrne sitting at a desk on an otherwise empty stage, surrounded on three sides by a giant beaded silver curtain. Holding a model of a human brain, he sang “Here”, from this year’s American Utopia album, and pointed to different sections of the brain: “Here is a region of abundant details . . . ” This is a familiar theme for Byrne, for whom music has always been as much physical as cerebral (hence the title of Jonathan Demme’s Talking Heads live film, Stop Making Sense).

As the show progressed through solo material and Talking Heads songs (“Lazy” came next, followed by “I Zimbra”), his band appeared on stage, all dressed in grey suits (Byrne was similarly attired, although his suit had extra pockets) delivering an experience that engaged both brain and body. Six (six!) percussionists, bass, guitar, keyboard, two singer-dancers; all instruments were strapped around their players’ necks. They marched, processed, retreated, circled, spiralled, in much the same way as the brass ensemble who played on Byrne and St Vincent’s tour in 2013 — but bigger, brighter, tighter, and rattling and clattering with percussive glee, the rhythmic patterns shifting from African (“Blind” featured a talking drum solo) to Latin. There are surely few finer sights than that of Byrne and his 11-strong ensemble advancing in synchronised steps towards the audience, playing a crackling, religious-ecstatic “Burning Down the House”.

There were pauses for a couple of public service announcements, in one of which Byrne nervously encouraged people to vote in local and regional elections, but otherwise this was a nonstop show, dipping between the distant past — “Once in a Lifetime” — to the present, with the exuberant “Everybody’s Coming to My House”.

The time-honoured ritual of the band disappearing and being called back for an “encore” was observed, giving the audience the chance to cheer more loudly than I think I can remember. Janelle Monáe’s protest song “Hell You Talmbout” ended the show — a chanted litany of victims of racial violence and law enforcement killings. This would have been the umpteenth time Byrne and his band had performed it, but their anger and indignation were absolutely real.

★★★★★