David Byrne: ‘How real do you need to be?’

Via Financial Times

© Jody Rogac

By Ludovic Hunter-Tilney

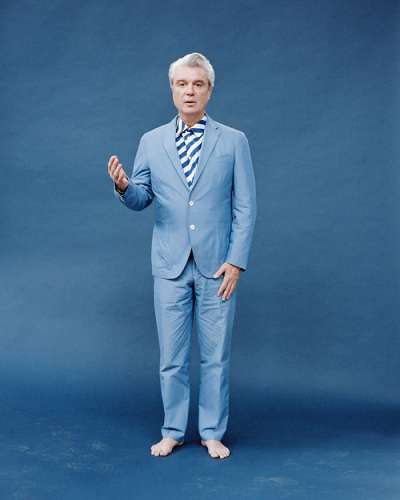

David Byrne has spent much of this hot summer sweating profusely in a grey suit. The outfit, designed by the fashion label Kenzo, features in the former Talking Heads frontman’s current tour. The dozen backing musicians and singers who join him wear identical suits. All are sodden by the end of most shows.

“I’m used to it from Talking Heads, getting soaked and stuff,” he laughs, a veteran of fetid East Village dives from New York’s 1970s punk rock scene. Our meeting takes place in a rather more upscale location.

We are in his dressing room at the Philharmonie de Paris, an extravagantly curvilinear Jean Nouvel-designed concert hall in the French capital. Copies of Byrne’s book How Music Works are piled on a table, waiting to be signed with rapid left-handed strokes of a pen. Tufts of white hair lie on the floor, residue of a pre-gig trim. The fold-up bicycle with which he always travels stands propped up near the door. Earlier he had cycled to the other side of Paris to see an exhibition about Japanese architecture.

Byrne was described in a 1985 New York Times profile as the “thinking man’s rock star”. By that point in their career Talking Heads were acclaimed as among rock’s most inventive bands, at once cerebral and danceable, conceptual and emotive. Now 66, Byrne has followed a quixotic path since his old band folded in 1991. There have been dance solo albums, collaborations, books and unclassifiable endeavours such as his multimedia “Reasons to Be Cheerful” project, which seeks nuggets of good news amid the vertiginous sense of looming disaster that increasingly grips the western liberal imagination. He is currently touring his first solo album in 14 years, American Utopia. The record had a mixed reception on its release in March. But the live staging has won unanimous praise during its travels.

He is currently touring his first solo album in 14 years, American Utopia. The record had a mixed reception on its release in March. But the live staging has won unanimous praise during its travels.

In the beginning with Talking Heads the idea was, let’s go back to ground zero, let’s strip away everything accumulated in pop music

Ingeniously conceived and choreographed, the production features Byrne and his troupe of musicians in an empty space bounded by three metal chain walls, playing wireless, portable instruments, each person with sensors that trigger their own lighting. A year in the planning, it is in fact the fruition of decades of thinking about live performance.

“In the very beginning with Talking Heads the idea was, let’s go back to ground zero,” he says. “Let’s strip away everything that’s been accumulated in pop music as far as how you are meant to move and what you are supposed to wear, how you’re supposed to be on stage.”

In How Music Works Byrne diagnoses himself as having suffered a mild version of Asperger syndrome in his younger days. Early in Talking Heads’ career he would stand rooted to the spot at the microphone stand, an introspective, intense figure, a kind of anti-performer. In contrast, his current show presents him as a liberated figure, moving freely with his backing musicians.

“For a while I was an incredibly shy person and the stage was the kind of compensation I had, that was the only way I could address people, by getting on stage and blurting out whatever. Now I’m very much less like that, so I’m more comfortable,” he says.

A turning point came after a Talking Heads tour to Japan in 1981. “I was constantly asking myself: ‘How spontaneous, authentic, improvisational does one need to be on stage? How real do you need to be?’ ” he says.

The discovery of stylised Japanese theatrical traditions such as Noh, and also a trip to Bali, where he saw staged religious rituals, provided an answer. Artificiality and exaggeration could be as real on stage as the most naturalistic mode of performance. “I started thinking that this idea of us just being ourselves on stage is useless. Then I began thinking about costumes and choreography.”

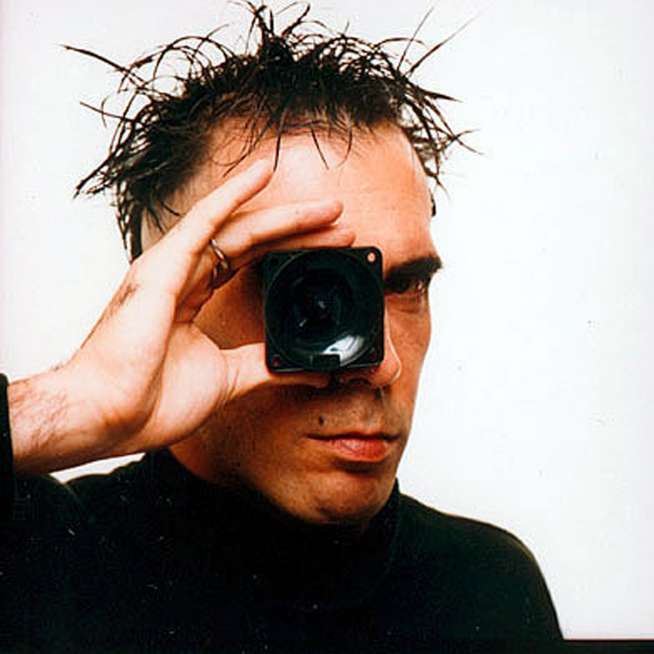

© Anthony Pidgeon/Getty Images

His thinking led to a landmark piece of rock theatre, Talking Heads’ 1984 concert film Stop Making Sense, made over the course of three gigs in Los Angeles. Byrne’s stage moves were a surreal masterclass of silent-movie slapstick and aerobics-style routines. He wore a grey suit for that performance too, which got more and more outsized as the gig progressed, a satirical take on 1980s power-dressing.

The Kenzo suit hanging on a rack in the dressing room appears to be a better-fitting descendant of the iconic Stop Making Sense outfit. But the association is unintended, Byrne insists. He professes disdain for nostalgia.

“I thought a long time about whether we should wear something more fantastic, something more colourful. Then I came back to thinking: ‘Let’s wear suits.’ By wearing very conventional clothes, we can allow that stuff to exist and it just doesn’t look like a lot of foolishness or wackiness. It has a little more gravity if you come out in suits.”

Six percussionists give new and old tracks in the set list a fresh energy. “It’s like a samba school or a second line in New Orleans,” Byrne says. “It has that feeling when it’s a mass of people playing, as opposed to one.”

Dance routines were devised with a regular collaborator, the choreographer Annie-B Parson of New York’s Big Dance Theater, who sees in his stage manner a legacy of British music hall traditions. Byrne was born in Scotland before moving as a child to Canada and then Maryland in the US. He did not take US citizenship until 2012.

© Sire Records/Michael Ochs Archives

Contrasting themes of estrangement and homeliness recur in his work. One of the songs in the set is Talking Heads’ “This Must Be the Place”, in which he sings: “Home is where I want to be/ But I guess I’m already there.”

“I’m probably using ‘home’ in the broader sense of: where does one belong? Where are you situated inside yourself, inside the family, inside the larger community, inside culture?” he says.

After making American Utopia, Byrne found himself on the wrong side of cultural movements, or at least the wrong side for a progressive-minded New Yorker. There were complaints the album included 25 male collaborators but not a single woman. The “thinking man’s rock star” issued an apology.

“I’m very aware of diversity being represented as best as can be in the band, in my office, in all the different kinds of work that I do,” he says. “It’s not just some kind of #MeToo pressure. You start to look at things in a different way. We have talks on the buses, or after the shows, everyone just talking about whatever is going on in the world. And you just go: this would be a different conversation if it was just a bunch of guys, or just a bunch of white guys. It would be a very different conversation. This is good.”

He would like to have “a giant bar” after shows, where the audience could mingle, discussing what they have seen, “if that could be the ending, not the last encore”. A central theme is music as a communal activity, a force for good in a violently divided world — in short, a reason to be cheerful.

“As one band member says: ‘We’re a little United Nations out here,’ ” Byrne says. “That in itself makes a statement but you never have to say it. The audience feel it and so do we. It’s how music affected me when I was young. It tells you that being odd or different might be OK and might even be fun. You’ve heard it from a million kids.

“Music tells them they’re not alone, there are other people out there who are like them or as odd as they feel themselves to be.”

Details of the continuing ‘American Utopia’ tour at davidbyrne.com