David Byrne Shares True Stories From 1986’s True Stories

By Cap Blackard

It’s 1986, and the American Dream has born strange fruits. Out in the vast expanse of the Midwest, prosperity is ubiquitous. Everything is good, or good enough. Leisure time has earned Middle America a hitherto unknown freedom of expression — and with it, tabloid-ready eccentricities.

This is the world of True Stories, David Byrne’s 1986 feature film and directorial debut “about a bunch of people in Virgil, Texas.” It’s part zany, slice-of-life comedy, part anthropological study — processed through the music of Talking Heads and projected through a loving, art house lens. It’s the most earnest portrait of ’80s America ever committed to screen, set against shopping malls, prefab warehouses, freeway cloverleafs, faceless tech buildings, fading small-town kitsch, and endless green acres of possibilities.

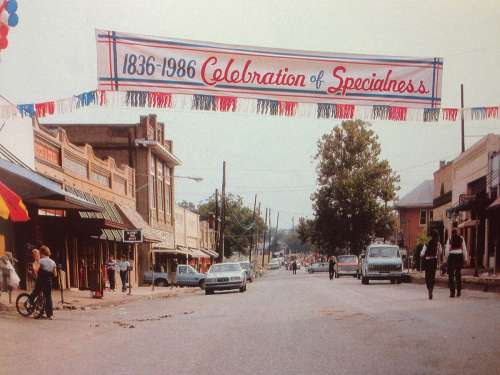

Disassociated vignettes and testimonials weave together as the town prepares for the Celebration of Specialness, their local commemoration of Texas’ sesquicentennial. At the center of it all is Byrne himself, a cowboy hat-wearing self-parody, who wanders into Virgil as a narrator figure. Alongside is Luis Fine, John Goodman in his film debut, a marriage-obsessed man who “maintains a very consistent panda bear shape” and writes sad songs that make you wanna lie on the floor.

Fine’s quest for “matrimony with a capital M” and Byrne’s inquisitive stroll through town play off an impeccable cast of characters, including Spalding Gray and Annie McEnroe (the couple who never speak to each other), Swoosie Kurtz (the woman so rich she doesn’t have to get out of bed), Tito Larriva (who hears radio signals in his head), and many more.

Altogether, these characters form a pageant of mundane modern wonder, celebrating the unassuming suburban grace of a plastic bag in the wind — long before American Beauty— and doing it in a rollicking style that could only come from one of the world’s greatest art rock outfits.

Byrne originally conceived of the story through saved tabloid clippings and photo references, which he turned into a feature-length screenplay alongside Beth Henley and Stephen Tobolowsky. However, the picture truly coalesced after Byrne received some key advice from his Stop Making Sense collaborator, the late Jonathan Demme.

“He pointed out the value of having something he referred to as a ‘clock,'” says Byrne. “He meant that you know something’s coming, and that as the film moves on, you know you’re going to get closer to it. You’re bouncing around, visiting all these different characters, but you have a sense that you’re headed somewhere. That helped cement the idea of the talent show at the end, and the parade and all that kind of stuff. And all you had to do was have people mention it every once in a while.”

Byrne describes the film as a “grab bag,” collecting not just wacky character portraits, but musings on architecture and inclusion of talent from all across the state, including different regional musical styles and the strange performances that made up the Celebration of Specialness.

“Some of it was based on actual acts that we could get in Texas that existed there,” he says. “The parade was an existing parade. We just inserted our stuff into it and said, ‘Well, we have a whole group of moms with their infants in baby carriages that we would like to be a part of this. And we have a marching accordion band, they would like to be part of it.’ And everybody in the town [where we filmed] said, ‘Sure. Yeah!’”

The portrait that True Stories paints of America may be a time capsule of its decade, but the gaze it casts is relevant as the nation struggles with its identity in the 21st century — asking the ever-present question best delivered in Byrne’s punchy “Once in a Lifetime” cadence: “Well, how did we get here?”

In the introduction to Byrne’s book on True Stories, originally released alongside the film, he writes: “Empires in retreat get into some pretty weird stuff — Egypt, Rome, England, Japan, Spain, and now the United States. They get this intense pride and nostalgia for what they imagine they are, and what they imagine they were, because they can see it slipping away.”

Of the above quote, Byrne was surprised at the stunning modern relevance and could only offer that perhaps it came from, “looking whatever was happening right in the eye.” True Stories may be a surreal slice-of-life comedy, but at its heart are penetrating insights into the heart of America.

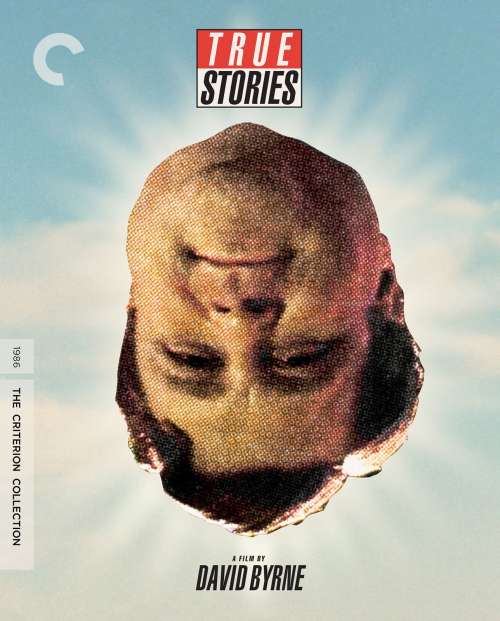

Over the years, the film has languished in one of the most cut-rate, bare-bones home video presentations ever known to humankind, and the score and cast recordings of Talking Heads songs have either long been out of print or never saw release at all. That gross injustice ends now as this unsung masterpiece of modern Americana and its complete soundtrack have been given a long overdue remastering and special-edition treatment at the hands of the Criterion Collection.

Pick up a copy of the Criterion release here. Listen to the full interview with Byrne here as he discusses the film and its evolution from tabloid clippings to cult classic with Consequence Podcast Network Director Cap Blackard.