David Byrne’s Joyful and Uncomfortable Reinvention of the Rock Concert

Via The Atlantic

Photo: PAUL R. GIUNTA / REUTERS

By Spencer Kornhaber

What once led David Byrne to don a comically enormous business suit while on tour with the Talking Heads, a choice made iconic by Jonathan Demme’s 1984 concert documentary, Stop Making Sense? Some answers are clear: He was sending up the era’s corporate culture, drawing from Japanese theater, and making a conceptually meta statement. “I wanted my head to appear smaller and the easiest way to do that was to make my body bigger,” the singer explained in an interview with himself. “Because music is very physical, and often the body understands it before the head.”

But still more important may have been the sensation evoked: joyful discomfort. Byrne looked like he was drowning in fabric, which seemed to retroactively explain why he always danced as if encased in gel. Yet the awkwardness was charming, like a kid trying on her dad’s jacket.

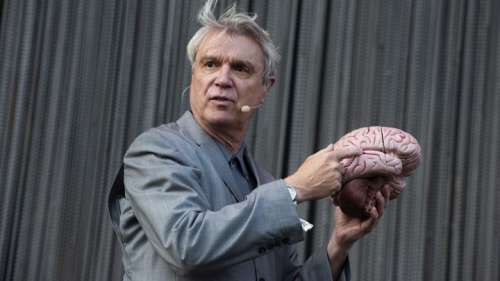

The captivatingly bizarre “American Utopia” tour that Byrne has undertaken for 2018 refines and extends the idea of the big suit. He and a dozen performers wear blazers and button-downs that are gray like the ones he wore three decades ago, though they’re of a saner fit. Visual disproportion instead comes from the staging: Byrne starts off alone, holding an oversized brain, dwarfed on three sides by tall walls of beads. When I saw him in Boston on Wednesday, the rest of the show neatly fit the description the critic Pauline Kael gave of Stop Making Sense more than three decades ago: It’s like “going to an austere orgy—which turns out to be just what you wanted.”

Byrne, at long last, has scrapped the essential trappings of a rock show. There’s no drum kit centering the eye. No amps stand like boulders. Rather, the musicians serve as the only furniture—and they move. Most play marching-band style, strapping their bodies with keyboards or a museum’s variety of percussion instruments (most concertgoers will struggle to identify the devices being thwacked and scraped). Each performer is also a performance artist, moving their feet and sticks in preplanned patterns. Joining them are two dancers, one of whom resembles Veep’s Matt Walsh in cabaret makeup.

Would it surprise anyone familiar with the Talking Heads to learn that the choreography is all stiff funk, graphical poses racked by jitters, people facing opposite directions or at perpendicular angles, and the robotic reinterpretation of wedding-party moves? The first chorus of Byrne’s recent American Utopia goes, “I dance like this / Because it feels so damn good,” and in concert this looks like a ritualistic hitchhike. Across the stage, the ensemble variously clusters and reassembles, sometimes receding behind the beaded curtains, sometimes peeking out from them, sometimes treating Byrne as leader, and sometimes ignoring him. Everyone is ebullient, but none more than the dancers Chris Giarmo and Tendayi Kuumba, who come off like aircraft marshals on ecstasy: sweaty, grinning, speaking with their arms.

Photo: Mario Anzuoni / Reuters

The happy hamminess of the disco maneuvers are certainly part of Byrne’s career-long fascination with the dorky middlebrow. But as with the big suit, the real power here is visceral: body over head. After all, the impulse to move, the reality of constraint, and the beauty of the two meeting each serve as eternal inspirations for Byrne. You can glean them in the Talking Heads’ catalogue and in his solo work, whether seen in his foray into color guard or heard on the surreal musings of the bustling American Utopia. “A dog cannot imagine what it is to drive a car,” he peals. “And we, in turn, are limited by what it is we are.”

The most potently jarring moment, at least in Boston, came when his love for that which does not quite fit was used for political ends. In the show-closing second encore, the ensemble covered Janelle Monáe’s “Hell You Talmbout,” a sternum-rattling chant memorializing black people killed by racist violence or state force (or both). The troupe became a protest line, standing shoulder to shoulder, shouting out names like Walter Scott and Trayvon Martin, and implicitly asking the audience to do the same.

Yet that audience—largely white, largely middle-aged—didn’t, as far as I could tell from where I was standing, shout back the names with any great unity or intensity. Maybe they didn’t understand the point of the song, or maybe they didn’t feel at ease participating. By the end, the divide between the thunderous energy from the stage and the meek rejoinder from the pit almost felt like the point. It highlighted why the song needs to be sung in the first place: to demand not only remembrance for the slain, but also reflection on the difficult question—especially for those caught off guard by the chant—of what to do about them. And it was a reminder that discomfort charged by passion is not only the emotional mix preferred by Byrne, but also, perhaps, the only kind that ever leads to change.