How did he get here? David Byrne’s American journey

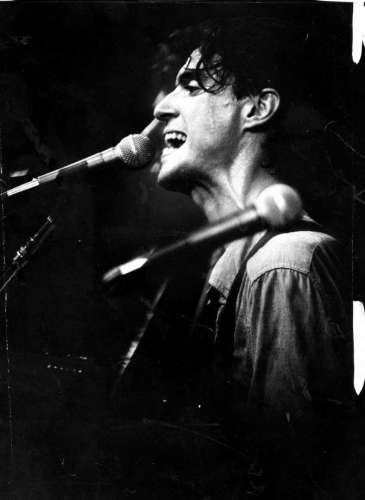

Photo: John Storey, Staff / San Francisco Chronicle

By Andrew Dansby

Let’s start at the end, shall we?

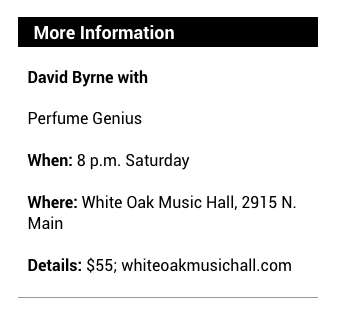

When David Byrne takes the stage at White Oak Music Hall Saturday, he’ll be holding a brain and playing the last song on his latest album. Fittingly, for those who have followed Byrne since his days in Talking Heads, the song is called “Here.”

“I got the brain at a medical supply place,” Byrne says. “And on stage, I say, ‘Here is this region,’ or ‘here is a section that does this.’ And I address different parts of the brain and ask the audience to look at it. And it all takes on a different meaning that sets the tone for the evening. It’s like I’m saying, ‘Here, look at who we are?’”

He’s done this before, years ago, iconically but to very different effect: “How did I get here?”

Byrne’s interest in how we got here has remained constant. But between 1977 and the present, his manner of processing that information has changed noticeably. With Talking Heads, Byrne conveyed a jittery distrust and paranoia for the world in which he floated around isolated as though he were in amniotic fluid. The oversize suit he famously wore in the ’80s wasn’t a prop, it was a metaphor.

What people loved and hated about Talking Heads had a lot to do with how Byrne — a guy born in Scotland, raised in Maryland and who cut his teeth in New York — viewed America as an insider/outsider. The view wasn’t often romantic.

In “Big Country” he recognized some value or beauty in the country outside his womb: the school, the houses with kids, the baseball diamond, the farmlands, the restaurants, bars, factories and buildings.

His response: “I wouldn’t live there if you paid me. I wouldn’t live like that, no siree.”

Regionalism, tribalism, snobbery about regionalism and tribalism: Byrne was picking at these scabs years before they ruptured into the bloody cultural mess we find ourselves in.

So when the guy who wrote “Big Country” titles a new album “American Utopia,” well, grab a helmet. Only Byrne’s new album isn’t a condemnation of anything. It’s anxious and jittery at times. But it’s also strangely hopeful. “Hey!” goes one refrain. “It’s not dark up here!”

So when the guy who wrote “Big Country” titles a new album “American Utopia,” well, grab a helmet. Only Byrne’s new album isn’t a condemnation of anything. It’s anxious and jittery at times. But it’s also strangely hopeful. “Hey!” goes one refrain. “It’s not dark up here!”

“I was hoping that might come across,” Byrne says. “Obviously it could be interpreted as somebody going up to an attic and discovering the lights are on. But I like to see it as something else. This, ‘Aaaah. Maybe things aren’t as dire as we thought. Maybe there’s a little hope.’”

Again, how did we get here?

Not a pivot point

I think something started to change nearly 25 years ago. If Bob Dylan’s second act could be summarized by a song with the refrain “I used to care, but things have changed,” Byrne has kind of flipped that script, even if he didn’t boil that thought down to two lyrical lines. His unstated mantra is along the lines of “I didn’t care, but things have changed … a little.” Some will see “American Utopia” as the pivot point, but it wasn’t.

“David Byrne,” released in 1994, is an underappreciated masterpiece. Its black-and-white cover is evocative of a stripping down of thoughts to the most basic, along with photos of Byrne’s hands, feet, chest hair and dental x-rays.

“For me, that record was my attempt to open up and be honest and write songs from the heart instead of songs about ideas,” he says. “For me that was a slightly new thing. I know for a lot of singer-songwriters it’s a starting point. And I was more than 10 years down the line. But I wanted the barest music, which was keeping with the lyrical and emotional content.”

The first song included the verse: “It’s not the ending of the world. It’s only the closing of a discotheque. I used to go three times a week. But that was a long, long time ago.”

Failure to put that in context in the work of a guy who wrote the much-circulated refrain, “This ain’t no party, this ain’t no disco” is lazy. But we can be lazy, especially with music, which we too often treat as grass: It grows, it turns brown for winter, it grows back — a needlessly fussy way to say, when a musician leaves a well-known band, we often don’t receive the new music with the same fervor.

Byrne being unsentimental about the past — he’s come a long way to be sentimental about the present — he’s always kicked forward to the next thing. While I favor “David Byrne,” all of his post-Heads work is rich for discovery by those with unyielding band allegiance.

There are connections between present and past. “American Utopia” has a few references to a car and one to a word music nerds will always tie to Byrne: “automobile.”

Not surprisingly the words “car” and “automobile” would fascinate him, both the metaphorical implications of the vehicle itself and the disparity between the one-syllable shorthand and the four-syllable counterpart.

“I love using the old word for things,” Byrne says. If not nostalgic for items, he can be for words. “I like slightly archaic or old-fashioned words for something. It puts a weird little spin on it.

“Now, I don’t have a car. But I realize people spend a very large part of their lives in their cars. I didn’t think about that much. So much that some people decorate their cars, which is fascinating to me. Not decorating like your Art Car Parade, but just people driving to work.”

In our age of us/them-dom, Byrne has become only more interesting as a commentator.

“Yeah, I thought about this the other day, to Europeans I’m very American,” he says. “And it’s funny because a lot of Americans assume I live in England. ‘Here’ is sort of about that. What is referred to as ‘ourselves,’ what’s within us.”

New born optimist?

The early reception to “American Utopia” has framed Byrne as a new born optimist, but it’s not quite that simple. “Gasoline and Dirty Sheets” digs a little into our thorny political present and includes the line, “The situation drags me down.” Lines about financial anxiety and cash surface multiple times.

After wearing dystopic goggles for so long, Byrne hasn’t traded them for a rose-colored set. But sometimes the worst in times bring out the best in cynics. He appears to have found some comfort outside of his comfort zone.

“He’s probably the most curious subtly curious person I’ve ever met,” says Terry Allen, the Lubbock-born musician and artist, also Byrne’s friend. “It doesn’t matter where you are or what situation you’re in with him, he’ll see something going on that you never had a clue about. But he saw it. And then he’ll want to talk about it. He doesn’t do small talk. I think that’s part of a shyness he has. But when he gets excited talking about something, you get excited about it. It’s usually about work.”

As Byrne sings on “Here,” the end of the new album and the beginning of his show: “Here is a region of abundant detail. Here is a region that is seldom used. Here is a section that continues living. Even when the other sections are removed.”

The observation sounds cold and clinical — he’s singing about the brain, after all, though it has metaphorical value, too. The lines possess admiration in the absence of affinity. But think of where Byrne started in the big country. The water isn’t holding him down. It’s holding him up. At least for now.