Interview: David Byrne

Via Film Comment

By Margaret Barton-Fumo

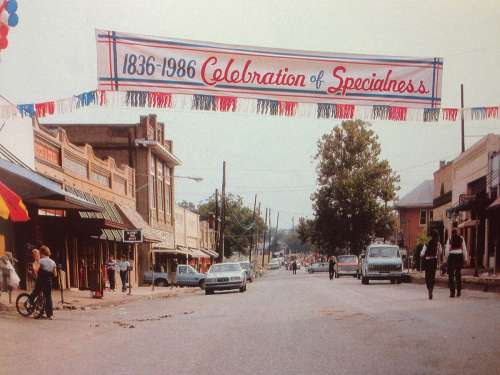

“I think it looks real in a new kind of romantic way,” David Byrne told Film Comment in 1986 on the release of True Stories. The movie’s tuneful chronicle of Virgil, Texas, and its preparations for a “Celebration of Specialness” anniversary parade is now available in a full-fledged Criterion Collection edition, as is the complete soundtrack from Nonesuch. For Film Comment, Margaret Barton-Fumo met with Byrne (who spent much of the year touring for his American Utopia album) to talk about the making of True Stories.

This may seem a little out of left field, but speaking of true stories: could you tell me a little about the Church of the SubGenius? It’s something I’d never heard of before I researched this film.

Really? And did you fall down a rabbit hole?

Just a little bit.

Church of the SubGenius is like a parody, ironic organization. I think a lot of their adherents are based out of Texas. [Laughs] Of course. A lot of their iconography is a guy named Bob Dobbs, this very ’50s businessman with a pipe sticking out of his mouth. It’s a very Devo thing, we’re gonna worship this guy with a pipe. They love a crazy conspiracy theory. So I took a little bit of inspiration from that when I was doing the scene with the preacher, who uses a preaching style and gospel kind of music, but he’s really talking about all these worldwide coincidences that he claims are all conspiracies. Gee, we have a lot of that these days! [Laughs]

Texas is also home to a lot of megachurches. I’d never seen churches with ginormous projection screens and all this tech stuff and room for thousands of people—like an auditorium, like a show almost.

Like a concert.

I’d never seen that before. I thought, wow, this is not like the little church in town.

So before True Stories, in 1981, you did the music video for “Once in a Lifetime.” Was that your first experience with directing?

I worked with Toni Basil, the choreographer, on that, but I’m not sure exactly how the credits read. We worked very closely. It might’ve been that I got the choreography credits and she got the directing credits, or the other way around. But around that period, yes, working on that and some other early videos, I learnt the rudimentary basics of editing—at least, music video editing. Different from film editing, but there are some similarities, which meant little by little, step by step, I could start to engage with TV or film as a medium. The early stuff was filmed on video, so it’s kind of funky-looking, but I graduated eventually to 16mm, and then to 35mm.

Are there any filmmakers that influenced you in your directing style?

Oh, yeah. Lots of people, lots of expected points of reference. The way Hitchcock would storyboard things out, that was just huge, and the imagery of Fellini and a lot of other European directors was amazing. The kind of narrative that didn’t seem to be a narrative in a lot of Altman movies. I was a big fan of experimental cinema: Bruce Conner, those psychedelic films, and things which rethought what you could do with a film, what the medium could be about. All these things were really wonderful.

Is it true that Errol Morris’s Vernon, Florida was a partial inspiration for True Stories?

Yes, I remember seeing that. I might’ve shown that to the writers. I remember showing the Chris Marker movie, Sans Soleil, to the writers I was working with, Stephen Tobolowsky and Beth Henley, which might seem like a bit of a stretch. I mean, I love the movie, but one of the things I thought might be inspirational to them was how he was taking all of these images that he liked and then he wove a story into it using this framework of letters that were being exchanged, and you would hear the letters being read over these images. It just made me think: there’s lots of ways to make a thread that goes through something, that helps engage us, and it doesn’t have to follow the same rules all the time.

I read that Jonathan Demme encouraged you to direct after your experience doing Stop Making Sense.

Jonathan Demme was very much a cheerleader. He was very helpful. His producer at the time, Gary Goetzman, was super supportive during the developing process. And Jonathan would look at what I was doing, and it was kind of outside of his wheelhouse, the things that I was doing, but he could offer really good advice. One of the things I remember he said was, “You need a clock.” [Laughs] He didn’t mean a clock on the wall, he meant something like a chronological thing that was coming in the future. In this film, it became the celebration of specialness in the talent show, so people at the beginning of the film people could say, “And in two weeks there’s gonna be a talent show.” Then you’d see somebody and they’re going, “We’re getting ready for the talent show!” So there’s this thing ticking and ticking, and it pulls you through a little bit—you know you’re heading toward something.

I loved the stage setup for the big showcase, the centennial celebration, that has that glowing frame around it.

Oh, that was Barbara Ling. That was her idea. Really wonderful.

Was she the art director?

She was the production designer, she’d done a film with Diane Keaton called Heaven. I really liked the way that looked, and I met with her. There were lots of picture books and architecture books and all kinds of things that we shared in interest, and I thought, yeah, we have some sensibilities in common. And for that [setup], she proposed using this material called zylon, which is this corrugated fiberglass. People use it for their back porches. The sun can’t quite go through, but it creates this kind of greenish glow. I thought, oh, that’s pretty cool, and it’s this cheap, get-it-off-the-shelf, hardware store kind of stuff. I don’t know what her next project was, but shortly after that, she was the production designer on Batman [Forever]. Whoa! Now you’re really getting to build some stuff.

I love that set for the showcase. It’s almost like they’re performing on a television set. It’s suspended above the audience.

It was really important that it be in the middle of a field and you don’t see all this other paraphernalia around it. It’s just like this kind of box in the middle of a field.

The Criterion release also has a feature about Tibor Kalman and his influence.

Criterion did a lot of great stuff. They did a shorter piece about Tibor Kalman, the graphic designer who I worked with on that film. He came in later and helped creatively with the slideshow in the beginning—the history lesson—with the titles, and that sort of stuff.

There’s also fantastic cinematography by Ed Lachman. How did you come across him?

I’d seen films that Ed had shot, like Wim Wenders’ films.

I think recently he’d done Desperately Seeking Susan, too. That was kind of the biggest one.

It might’ve been the biggest one, but I think it was the slightly artier ones that really drew me towards him. Like Barbara Ling, when we met we both had lots of picture books to share with each other. In this case it was the work of a lot of what were called the New Color Photographers: Bill Eggleston, Joel Sternfeld, Joel Meyerowitz—a bunch of people who were getting seen at that point and being appreciated, despite the fact that there was some resistance to people taking color photography seriously. But we would look at their framing and the color and all that kind of thing, and go, “That would be a great way to approach Texas.”

The colors are very vibrant, it’s beautiful. And you also drew from tabloid stories to come up with True Stories.

Yeah. The fat boy stories came later. First there was the wall full of images and storyboards, and then there was some more stuff—maybe clippings from the Weekly World News, and some people who live in their own way. Maybe, I thought, looking at one of these articles, here’s a character looking for a wife, and he can appear here and there throughout, and he has to get a song… And then gradually, some of those stories got attached to certain characters.

I found it interesting that in your recent lecture series, “Reasons to Be Cheerful,” you went back to the newspapers again and found more actually true stories. The story about the Texas politician who—

That’s a good story!

I felt like he could have existed in the town of Virgil.

He could have, it’s about that size. I’m still doing that stuff. I had a new one that I worked on this morning about various places that are divesting from fossil fuels.

Going back to True Stories, I have a note: “John Goodman.”

John Goodman. John Goodman. John Goodman was incredible.

Did you cast him?

I think it was Vickie Thomas, our casting director, who brought him to our attention. He is wonderful. He was in something on Broadway at the time, a musical called Big River. He took off pretty quickly after that. And I remember, I was pushing for somebody else to play my part. One of the people I liked was a radio announcer guy who had a very peculiar delivery. He would insert pauses into his delivery in really odd ways. One of his catchphrases was: “And now for… the rest… of the story.” [Laughs] I adopted some of those!

I like how you said “special…ness.”

This guy had some eccentric vocal things that he did with his readings, and I wanted him. But I got persuaded to do it myself. I had no ambitions to be an actor, although it was fun. The directing part was the joy, not the acting part, for me.

And you never directed a feature again?

I did a documentary in Brazil [Ilé Aiyé: House of Life]—a very different experience to doing something that’s scripted. But I, again, enjoyed it immensely.

For the Criterion release, I think they’re releasing the music again but this time with the actor’s vocals, which you didn’t do the first time around.

Which I felt was unfortunate, but… commercial pressures. This time there’s a CD that contains all the music in the film, in the order that it’s in the film. So occasionally there’s a Talking Heads song, and then there’s a song where it’s Talking Heads playing but it’s one of the actors singing, and there’ll be various bits of score and instrumental or whatever in between that, and it plays pretty well.

I love the kids’ song as well.

Oh, thank you. [Laughs]