SHOW STOPPER — Global

Via Monocle

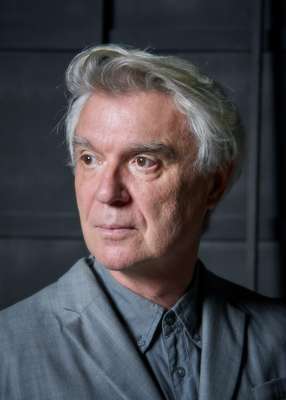

Photo: James Mollison

By Holly Fisher

On a stage framed by a chainmail curtain, David Byrne strums the familiar introduction to one of his biggest hits. His 11-strong Kenzo-suited team of dancers and musicians (in this performance, everyone is both) have their backs to the crowd until the drums kick in. That’s when the band spins around and the former frontman of Talking Heads roars the opening line of “Burning Down the House”. Everybody in the theatre stands on their feet.

Each stop of his extraordinary American Utopia tour, which has touched down from Buffalo to Belo Horizonte and Bilbao, has dazzled its audience. Byrne believes this is the most ambitious performance he has staged since Talking Heads’ 1984 Speaking in Tongues tour. A writer, actor and filmmaker as well as a musician, Scottish-born, New York-based Byrne has long been thinking of ways to innovate live gigs. In his book How Music Works he talks of how any performance must achieve something interesting. Some of his early ventures on stage included shaving his beard live: a memorable idea but not for the squeamish (you try handling a razor without a mirror).

Now, at the age of 66, he has settled for something more structured, combining his creative vision with technological trickery – think ingenious lighting and wireless instruments. The result sits somewhere between a concert, an art performance, a musical and a carnival; overall an energetic masterpiece that has seen critics praising him for reinventing the gig.

Choreographed by Byrne’s long-term collaborator Annie-B Parson, the musicians roam the stage freely with their instruments attached to their bodies. Light tricks devised by Rob Sinclair add an element of spectacle – and leave most wondering why nobody has put on a show like this before. The answer is that, probably, nobody thinks about performance quite like David Byrne.

Monocle: When did you have the initial vision for this show?

David Byrne: It was as some of the songwriting was taking shape, which was about a year or so ago. It sounded like some of it had a fair amount of percussion and drum rhythm, so I started thinking about samba schools and marching band drumlines. I thought it’d be so much fun if we could do the whole thing mobile.

M: Have music and movement always come hand in hand for you?

DB: Probably since the early ’80s. Before that there was almost no movement. I didn’t know what to do but I knew I wanted to be very careful and not just do, by default, what rock’n’roll bands do. I didn’t want to adopt poses that I’d seen and assume that’s what you do if you’re in a band. We had to find a way that had meaning for us, that fit our music and what we were about. In the early ’80s I started experimenting with a bit of movement and then added more and more as years went by; it was a cumulative process. Other than Chris and Tendayi [backing vocalists and dancers], the rest of us [in this show] are not trained dancers so we do the best we can. It’s a little sloppy and loose – it’s not super-precise, there’s a bit of each person’s own expression in it.

M: Each show closes with a Janelle Monáe protest song that’s called ‘Hell you Talmbout’. You have also had a charity called HeadCount at your concerts in the US to encourage people to register and vote. Is there a political side to your gigs?

DB: [Monáe’s] song is the best political song I’ve heard in a long time. When it came to doing a set in the present climate, I thought I would love to do something that implies if not activism, at least an awareness and engagement. We’re moving through a lot. I believe there are some countries where a larger percentage of people vote than in the US, but there are still a lot of places where the turnout is as pathetic as it is there. The upheavals, tensions and splits that have been happening in the US are happening everywhere. People really need to have their voices heard.

M: Is that why you’ve started doing your Reasons to be Cheerful talks, where you discuss positive stories from around the world?

DB: That started a couple of years ago. Probably like a lot of people, I’d wake up, read the morning paper over breakfast and be in a foul mood for a couple of hours. I didn’t want to stop reading the paper but I needed something so I wouldn’t end up a mean, angry cynic. So I started collecting things that seemed somewhat hopeful to me. I started doing talks to show what I’d found – and it worked. A lot of these things are either from smaller countries or they’re the initiatives that come out of a city. Only occasionally it’s a nation. It’s a fair amount of work: I don’t want it to be just me linking to articles I’ve seen; I want to be a little bit more thoughtful, fact-check any claims and make sure that these initiatives have actually been successful.

M: In your book you discuss the hierarchy of a band on stage. Is that something that you have always been interested in trying to break down?

DB: Yes, in many cases I feel that part of the enjoyment for the audience is seeing how a group of disparate individuals can come together as a community and create something. You’re not going to get that if you just have the frontman or woman and a faceless bunch of musicians in the back. If you can get a sense of each of them as an individual, that gives an extraordinary feeling to the audience. It’s something that happens so rarely in life – and yet you’re seeing it in a show like this. It makes you realise it’s possible for people to work together and get along.

M: How did you pick your band? You have musicians and dancers but sometimes the line blurs between who is what.

DB: Exactly. At some point in my previous tour I realised that some of the dancers played instruments so I started asking them to play as well. As much as I could, I also wanted to blur the lines of race and gender. The band says it is like a little United Nations up here. I’ve learned from some of the theatre I’ve done that having this kind of diversity on stage makes an unspoken statement which the audience gets.

Behind the curtain:

It might look simple but pulling off choreography and lighting for a 12-member fully wireless band is a huge undertaking. “I didn’t realise quite how revolutionary [it was] until the show opened,” says lighting designer Rob Sinclair. “I spent most of my life with a drummer in the middle of the stage. All of those rock concert tropes were taken away, which made us think about everything we did.”

Choreographer Annie-B Parson is also keen to avoid those tropes. She and Byrne have collaborated for more than a decade. “When he said he was interested in me choreographing, my first response was, ‘Wait! You’re my favourite choreographer, I don’t think you need me!’” she says, laughing.

The production elements of the show were put together in Lititz, a small town in Amish country. Sinclair and Byrne spent two days there “playing with shadows and mucking about”. Eventually they decided to adopt some new technology for the show: sensors are sewn into every band member’s suit shoulders so that Sinclair can track and light them. The stage is lit up in bold colours that change from song to song. Musicians disappear in and out of the infinite entrances and exits to the stage that the chain curtains provide; the characters move and interact with the ease of a close-knit group. By the time the show’s over, each of them has had their moment in the spotlight – a testament to Byrne’s non-hierarchical band management.