Still Making Sense

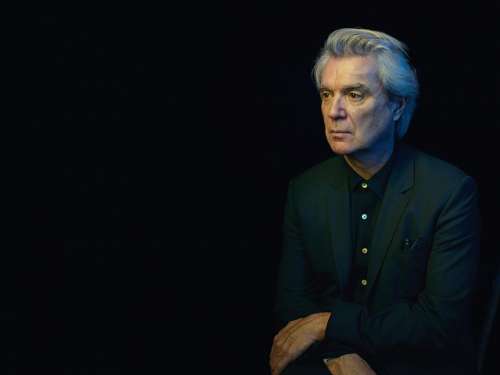

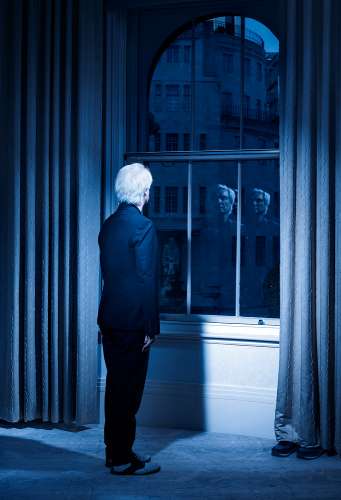

Photo by Nadav Kander

Written by Charlie McCann

David Byrne wears the mess kit of the music-industry musketry: black jacket, black shirt, black trousers. But the Scottish-born musician, whose distinctive voice and strikingly original fusion of genres marked out the American band Talking Heads as soon as it arrived on the scene in 1975, is anything but regular. He doesn’t shake my hand or look at me when introduced. He won’t cast an eye on the results of the photo shoot, saying it would make him feel “self-conscious”. In his bestselling 2012 book, “How Music Works”, Byrne said he had border-line Asperger’s syndrome, an autistic disorder often characterised by above-average intelligence and social awkwardness. He calls himself “an anthropologist from Mars”.

His subject is the ordinary. Now 65, Byrne has made a lifetime study of everyday people, places and objects. He likes to look at things clinically yet with irony, which helps make the commonplace seem strange. In “Stop Making Sense”, the 1984 film of a live Talking Heads concert directed by Jonathan Demme, Byrne performed in a massive, boxy suit, so his head looked as if it had shrunk. “I try to write about small things,” he said in the film. “Paper, animals, a house.” As he has grown older, Byrne’s ambition has become bigger. Grappling with the question of how pop should respond to politics, he has now released his first solo album for 14 years, “American Utopia”, and has just started a world tour.

The music that Byrne made in the early days of Talking Heads was radical, not for what it had to say about the wider world of politics but for what it had to say about rock. When the band landed their first gig in 1975, on the stage of a dirty little club in New York called CBGB, the punk vanguard was making raw, swaggering music that looked to an earlier era of rock’n’roll, which groups like the Ramones admired for being less pretentious and overblown than prog-rock. But Talking Heads wasn’t interested in the past. Its members began to meld their art-rock with funk and disco, genres often scorned by rock fans, and came up with something entirely new. On the intoxicating 1980 masterpiece, “Remain in Light”, lauded as “visionary” by Robert Christgau, a leading rock critic of the time, the band scrapped the rules governing how to structure a pop song: prioritising rhythm and texture over melody, they created a euphoric groove more reminiscent of African music than rock. It proved that pop could be both avant-garde and commercially successful. A multitude of later bands, from Vampire Weekend to Arcade Fire, were influenced and inspired by the group.

Even before Talking Heads broke up in 1991, Byrne was pursuing a dizzyingly productive solo career. He directed films, started his own world-music label and wrote books, musicals and scores for opera, ballet, film and theatre. He became more politically active, spearheading a prominent coalition of musicians campaigning against the Iraq war. In February 2016, just as he began working on “American Utopia”, he published an essay on his website that attempted to explain the rise of Donald Trump, bringing in Alexander Hamilton, as well as John Rawls, a political philosopher who died in 2002, and Cass Sunstein, a legal scholar. In it, he said that declining social mobility had contributed to a “feeling of impotence” among Americans crushed by “the end of the American dream”. Before the 2016 presidential election he went to North Carolina to encourage people to vote.

“American Utopia” is the product of that angst. Where once he cobbled together lyrics based on how the syllables sounded against the music, increasingly he began to write lyrics that said something. On the record, Byrne draws the listener’s attention to the country as he sees it (and not, as the title suggests, how he would prefer it to be). He shows us office blocks, houses, parks and the people who inhabit them: tired workers, a hung-over judge, revellers at a house party that got out of hand, a “credit-card mommy” and an “invisible dad”.

These are regular people with regular victories and defeats. “Every day is a miracle,” Byrne hollers joyfully. “Every day is an unpaid bill.” The music is deliciously sinuous – strands of bass, electric guitar and percussion are braided together, accented with horns, harpsichord and sitar – so much so that you almost don’t notice at first that somebody is declaring that “freedom costs too much”; that a man has been shot; that some people are being told to leave their homes, even though they have nowhere else to go. The shocking is made to seem routine.

Byrne hopes that the album will encourage listeners to take a long, hard look at America and ask whether they like what they see. But he doesn’t ultimately think his songs are going to change anyone’s mind about the country’s direction of travel. He wrote in “How Music Works” that he didn’t believe that protest music could be used to persuade. Though it may articulate what people already feel, it’s “maybe not the best way to change people’s minds”.

Photo by Nadav Kander

Now he says, almost shyly, that music may be capable of something both subtler and more powerful. With “American Utopia”, he is testing his hypothesis on stage. “This might be kind of a stretch,” he says, his face creasing into a wry smile, but sometimes “the performance of music can be a metaphor for a social attitude. In certain kinds of music, it takes everybody playing together to make it sound good.”

Byrne tells me that the concert for “American Utopia” will be as “ambitious” as “Stop Making Sense”, which is widely regarded as an exemplar of art-rock showmanship. Enthusiasm creeps into his voice. “I’ve realised that with contemporary technology, I can liberate all the musicians, even the drummer and keyboard player.” The musicians will strap their instruments to their bodies: there will be no stands, cables or amps. Freed from the rocker’s usual accoutrements (the stage will be completely empty, with no visuals), “everyone can be mobile” and their movements choreographed. There will be 12 musicians in the band, half of them drummers; the drum kit is being taken apart so that six people will play a set normally used by only one. “The fact that it will take 12 people to make the sound – there’ll be a visceral impact. Everything we do on stage will be about our connections, our working together, and our arrangement as human beings.”

Since Byrne started writing this album, Americans have grown used to the sight of Donald Trump peacocking on stage as he whips the crowds at his rallies into a frenzy. Byrne’s gathering will be different. He will wear the same clothes as the rest of the band and dance the same steps. Their music will bring together a community of people united, even if for just a few hours, by a common purpose. It will be a spectacle celebrating egalitarianism – Byrne’s very own American utopia.