Strange Overtones - David Byrne’s ‘American Utopia’ Tour

Via Scoop Media

Photo: Paul Wellman

By Howard Davis

"The mind is a soft-boiled potato" - David Byrne

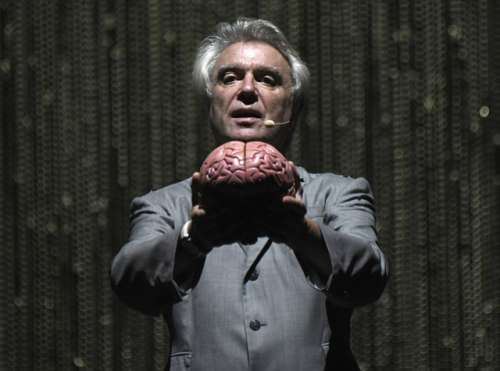

Scotch-born singer-songwriter David Byrne starts each show on his latest world tour stroking a pink brain as he sits alone at a table in a gray three-button suit singing a song called Here from his latest album American Utopia. It is the only splash of colour on an otherwise barren stage, encircled by shimmering beaded curtains. "Here is a region of abundant details," he intones. "Here is a region that is seldom used / Here is a region that continues living / Even when the other sections are removed." By the final verse, he is joined at the table by two backup singers, harmonizing with his vocals as he starts to pace back and forth at the front of the stage, using the model as a visual aid as though teaching a high school anatomy class. Such a cerebral approach is precisely what audiences have come to expect from Byrne, whose querulous, queasy, and querying approach appeals equally to adolescents and lateral thinkers. His previous expression of puzzled and anxious surprise as erstwhile bandleader of Talking Heads has mellowed into a more concentrated, quasi-academic demeanour which nevertheless retains much of its original quirkiness.

Like Peter Gabriel, who also quit a highly successful progressive rock band at the peak of its success, Byrne has been a champion of world music for decades, particularly the intoxicating pulse of Latin, Caribbean, and South American rhythms, with their adventitious use of percussive effects such as cowbells and congas. Byrne founded the world music record label Luka Bop in 1990, originally to release Latin American and Brazilian compilations. It has grown to include music from Cuba, Africa, the Far East and beyond, releasing the work of such artists as Cornershop, Os Mutantes, Los De Abajo, Jim White, Zap Mama, Tom Zé, Los Amigos Invisibles, and King Changó. In 2005, he started his own internet radio station, Radio David Byrne, on which he posts a monthly playlist of music he likes, linked by themes or genres, including African pop, country music, vox humana, classical opera, and Italian movie scores. The connective tissue between both Gabriel and Byrne is provided by the oblique strategies of producer Brain Eno, who first collaborated with Talking Heads on their 1980 album Remain In Light, before co-producing with Byrne the brilliantly coruscating My Life In The Bush of Ghosts (1981), which attracted critical acclaim for its pioneering use of analogue sampling and found sounds. It was re-released for its 25th anniversary in early 2006, with new bonus tracks; in keeping with the spirit of the original album, stems for two of the songs' component tracks were released under Creative Commons licenses and a remix contest site was launched. In addition to working with such idiosyncratic artists as David Bowie, Bono, Robert Frip, and John Cale, Eno has produced Gabriel's his most ambitious albums. All these musicians share a passion for exploring unorthodox and unexpected avenues of expression, as well as a fascination with propulsive rhythms that owe little to rock and roll.

Equally influenced by the experimental theater in New York that he absorbed as a Rhode Island School of Design student in the 1970s, the sixty-six year-old Byrne has always been interested in the the visual arts, drama, and dance, having dated Twyla Tharp, Tony Basil, and Cindy Sherman in the past. In 1981, Byrne partnered professionally with Tharp, scoring music that appeared on his album The Catherine Wheel for a ballet with the same name, which featured his trademark spikey rhythms and obscure lyrics. A stage production appeared on Broadway that same year. He invited Spalding Gray to act in True Stories and asked Meredith Monk to provide part of that film's soundtrack. In 1991, Byrne released The Forest, a classical instrumental album that included some of the tracks featured as a score for Robert Wilson's 1988 theatre piece of the same name. The Forest maxi-single contained dance and industrial remixes by Jack Dangers, Rudy Tambala, and Anthony Capel. He also wrote a Dirty Dozen Brass Band-inspired score for Wilson's opera The Knee Plays, from The Civil Wars: A Tree Is Best Measured When It Is Down, and produced a soundscape called In Spite of Wishing and Waiting for Belgian choreographer Wim Vandekeybus' dance company Ultima Vez. In late 2005, Byrne and Fatboy Slim worked together on Here Lies Love, a wonderfully weird disco/opera song cycle about the life of the disgraced First Lady of the Philippines, Imelda Marcos.

In addition, Byrne has been involved in many movie soundtracks, notably collaborating with Ryuichi Sakamoto and Cong Su on Bernardo Bertolucci's The Last Emperor, which won an Academy Award for Best Original Score. Byrne himself wrote, directed, and starred in True Stories, a musical collage of discordant Americana released in 1986, as well as producing most of the film's music. He directed the documentary Île Aiye and the concert film of his 1992 Latin-tinged tour titled Between the Teeth. Together with Celia Cruz, he supplied Loco de Amor for Jonathan Demme's 1986 film Something Wild. He scored JoAnne Akalaitis' film Dead End Kids, based on a Mabou Mines theatre production, and collaborated with Eno on the soundtrack for the film Wall Street: Money Never Sleeps. In 2004, Lead Us Not into Temptation included tracks and musical experiments from his score to Young Adam, and in 2008 he released Big Love: Hymnal, his soundtrack to season two of Big Love. These two albums constituted the first releases on his independent record label Todo Mundo.

Clearly a man of broad interests and equally great taste, Byrne's visual art has been exhibited in contemporary galleries and museums since the 1990s, represented by the prestigious Pace/MacGill Gallery in New York. In 2006, Byrne released Arboretum, a sketchbook facsimile of his Tree Drawings, and in 2010 his original artwork was in the exhibition The Record: Contemporary Art and Vinyl at Duke University's Nasher Museum of Art. In 2015, Byrne organized Contemporary Color, two arena concerts in Brooklyn and in Toronto, for which he brought in ten musical acts who teamed up with ten colour guard troupes. The concerts were also made into a documentary film, directed by Bill and Turner Ross, and produced by Byrne, in 2016.

As if he weren't been busy enough, Byrne is also known for his activism in support of increased cycling and for having used a bike as his main means of transport throughout his life. He began cycling while he was in high school and returned to it as an adult in the late 1970s, when it was the preserve of “loners, losers, maniacs and nerds,” preferring the freedom and exhilaration cycling provides. The other members of Talking Heads used to make fun of him, calling him Pee-wee Herman, after the dorky TV character. Although he drives a Citroen DS when in LA, he does not drive at all in New York. In 2008, he designed a series of parking racks in the form of image outlines corresponding to the areas in which they were located, such as a dollar sign for Wall St and an electric guitar in Williamsburg, Brooklyn. Byrne worked with a manufacturer that constructed the racks in exchange for the right to sell them later as art and they remained on the streets for about a year. He has written widely on the benefits of cycling (including a 2009 book, Bicycle Diaries), and in the same year auctioned his Montague folding bike to raise money for the London Cycling Campaign. Whenever Byrne arrives in a city, even if it is only for a few hours before a show, the sixty-six -year-old musician likes to see some culture, grab something interesting to eat, and ride his bike. For his current tour, he has subsidised a small fleet of fold-ups and many of his band join him on these excursions.

Byrne's first solo album after leaving Talking Heads, Rei Momo (1989), featured a plethora of Afro-Cuban, Afro-Hispanic, and Brazilian popular song styles including merengue, son cubano, samba, mambo, cumbia, cha-cha-cha, bomba, and charanga. His third solo album, Uh-Oh (1992), also employed a brass section and was driven by catchy tracks such as Girls on My Mind and The Cowboy Mambo (Hey Lookit Me Now), while his fourth, eponymously titled David Byrne (1994), went back to his rock roots, with Byrne playing most of the instruments and leaving only the percussion parts to experienced session musicians. Angels and Back in the Box were the two main singles released from the album. For his fifth studio effort, the overtly emotional Feelings (1997), Byrne returned to a brass orchestra. His sixth, Look into the Eyeball (2001), explored similar musical territory as Feelings, but with somewhat more upbeat tracks. Grown Backwards (2004) employed orchestral string arrangements, included two operatic arias, and a reworking of an X-Press 2 collaboration, Lazy. He also launched a North American and Australian tour with the Tosca Strings, ending with a New York show in August 2005. Byrne and Eno reunited for his eighth album, the entirely delightful Everything That Happens Will Happen Today (2008), for which he assembled a band to tour worldwide for six months on the Songs of David Byrne and Brian Eno Tour.

In 2012 Byrne released the collaborative EP Brass Tactics and an album with St Vincent called Love This Giant, which makes American Utopia officially his first solo album in 14 years. Released in March 2018 through Todo Mundo and Nonesuch Records, it included the single, Everybody's Coming to My House, co-written with Eno. Byrne was also assisted by London XL Recordings subsidiary Young Turks, a phalanx of electronic producers drafted in to create some entirely novel soundscapes. I Dance Like This is probably the most jarring track of the new album, with a chorus that tends towards the industrial and includes the classic lines “I dance like this because it feels so damn good/If I could dance better, well you know that I would." Performed live, it was one of the show’s highlights, more heavy metal than machine music. In 1990, I was fortunate enough to see Byrne perform songs from Rei Mambo at London's sweaty Brixton Academy with a twenty-piece band of superb Latin American musicians. Twenty years later, on a balmy evening in Los Angeles, I saw him playing Everything That Happens Will Happen Today, outdoors at the Hollywood Bowl. There can hardly be two more contrasting albums or venues - but in both cases the audience was up on its feet within a few minutes. New Zealand is at the tail end of an eighty gig global tour which showcases songs from American Utopia, alongside highlights from his Talking Heads and solo career. The NME described Byrne's it as perhaps "the most ... impressive live show of all time," blurring the lines "between gig and theatre, poetry and dance." It is certainly approaches the high-water mark set by Stop Making Sense, Jonathan Demme's extraordinary 1984 film of Talking Heads’ concept-heavy Speaking in Tongues tour, which few musical documentaries have managed to emulate.

Demme's movie is self-reflective riot of stylised dancing and constantly expanding suits that critic Pauline Kael compared to the work of Jean-Luc Godard and applauded as “close to perfection." Byrne explained his choice of the outsized suit as a device to make his head appear smaller - “Because music is very physical, and often the body understands it before the head.” At the end of last year, Byrne tweeted that his forthcoming world tour was “the most ambitious show I’ve done since the shows that were filmed for Stop Making Sense." The new songs, plus a few Talking Heads tracks he is not completely fed up with, are accompanied by a radical theatrical show. Byrne spends a lot of time trying to reimagine live performances, initially because he was awkward on stage, but these days because it keeps it more interesting for him. The result for this tour is an empty set in front of a shimmering curtain, with no amps, risers or stands, and Byrne leads his troupe of a dozen performers who are in constant motion. “I can’t imagine doing a show with amps now,” says Byrne. “If you take those away, it’s almost like you can float in the air.”

One of the secrets of Byrne’s continued success is his amaranthine focus on funk-fueled extemporizations and rhythmic thrust. His twelve piece band is in near-constant motion, with a heavy emphasis on percussion. At several points in the show, half a dozen musicians play bits of drum kits hanging off harnesses, a cross between the Kitchen Sink sketch from Stomp!, Brazilian batteria, and a high school marching band. Everyone is barefoot and stylishly attired in grey Kenzo suits. Sometimes Byrne gnomically rolls up his trouser leg to reveal an ankle, or his jacket sleeve to reveal an inner elbow, and he hitches up his pants comically at the end of several songs. By all accounts soft-spoken and unassuming in person, when performing he scampers around the stage like a man possessed. Both his and backing vocalist Chris Giarmo’s jackets were soaked in sweat by the end of the show. Although it is never made entirely clear what precisely motivates these frantic moves, contortions, and gyrations beyond their wistful entertainment value, they certainly contribute to the air of unworldly otherness that Byrne clearly enjoys cultivating.

Photo: Ralph Freso, Special for azcentral.com

Movement, rhythm, and dance fuse together seamlessly in front of a set that is sombre and minimal. Choreographed by Annie-B Parson, the band synchronizes into clumps or lines, posing, vogue-ing, and circling backwards (a compulsive movement previously evident in Contemporary Colors, which reinterpreted the flag-spinners who combine with marching bands for half-time performances in US sports arenas). The musicians play everything live without backing tracks, amplifiers, or drum risers, while the percussionists perform with their instruments hanging around their necks. Their every movement is highly stylized in a manner that sometimes seems eerily familiar. The old favourites are pure pleasure, spanning moods as diverse as I Zimbra, This Must Be the Place (Naive Melody), and magnificent versions of Born Under Punches and Once in a Lifetime. Byrne’s performance of the latter recapitulates the opening of Demme’s film, where he flung himself around the stage in a demented frenzy to the spastic beat of Psycho Killer. Previous Talking Heads songs and solo outings drawn from various periods, covers, and collaborations are all subtly re-scored to create a show heavy on bass dance grooves and dramatic changes of pace, all wound tighter than a coiled mainspring.

Such a theatrical approach is not without risks. A show in which even the way the backup singers stand between songs is rehearsed faces the danger of feeling over-orchestrated, and there are moments when the band resemble participants in a jukebox musical based on Byrne’s past oeuvre, like some kind of crazy samba band or column of deranged ice-cream vendors. Nor is Byrne blessed with a great vocal range or even an especially strong voice, often sliding up and down the scale in a tremulous glissando, but he compensates for these deficiencies by a great ear for catchy hooks and simple melodies. More often, this faux naif approach is disarmingly intriguing and strangely captivating. The staging of Blind (a dense, writhing track from Talking Heads’ final album, Naked) is both simple and powerful, the musicians all standing in a straight line, illuminated by a single keylight that casts vast, shivering shadows over the stage. The show works best when the precision of the staging grinds up against the visceral, urgent music and the setlist delves into Talking Heads’ back catalogue, reminding the audience just how wonderful such songs as Born Under Punches, Once in a Lifetime, and The Great Curve really are, how intelligently they blend disparate genres together, at once abstractly conceptual and full of funk.

Behind the battery of South American percussion, the songs from American Utopia sound closer to New York indie bands like The Magnetic Fields, albeit with their dolorous lyrical sarcasm replaced by more whimsical lines like - “The chicken thinks in mysterious ways.” The jarring musical shifts of I Dance Like This, during which strobe lights flare about and the dance routine continues unabated during a lengthy silence, are charming rather than infuriating. The show ends on a more sombre note, however. For their second encore, Byrne and his band discard the choreography and launch into Janelle Monáe’s 2015 anthem Hell You Talmbout, chanting out the names of young African Americans killed by police and vigilantes. It is a powerful response to anyone who finds American Utopia’s vision of the US too playfully twee, providing an austere finale to a mesmerizing and entrancing evening.

David Byrne & Kimbra played the TSB Arena, Wellington, on Tuesday, 13/11. Upcoming gigs are at the Horncastle Arena, Christchurch, on Thursday 15/11, and Spark Arena, Auckland, on Saturday 17/11.