True Stories

Via Slant Magazine

BY JAKE COLE

True Stories

NOVEMBER 29, 2018

As the frontman for the Talking Heads, David Byrne constructed a persona of nervous anxiety—a mercurial blend of ironic kitsch and earnest sentiment—pitted against the baffling ways of a rapidly modernizing world. Inspired by local tabloid stories and personal sketches he made while touring, 1986’s True Stories is clearly the product of this artistic mindset.

The film’s opening, in which Byrne narrates the history of the fictional Texas town of Virgil from the Precambrian era to the present in a flat yet amiable voice atop what sounds like a parody of Philip Glass’s Koyaanisqatsi score, is suffused with Byrne’s idiosyncratic sense of humor. The film’s attempt at an all-encompassing history of Texas mingles everything from depictions of territorial wars with tribes to accounts of semiconductor innovations, and the narrator’s dry recitation positions Byrne’s unnamed figure as a warped tour guide, spouting off facts that become increasingly esoteric.

Byrne’s narration prefigures a film that lacks any particular through line. Using Texas’s sesquicentennial celebration as an anchor, True Stories drifts through largely narrative-free vignettes featuring oddball characters. John Goodman plays the closest the film has to a protagonist in Louis Fyne, a lonely heart who searches for a bride who will accept him for his portly self. As he says with world-weary defiance in a video recorded for a dating service, “I’m six-three and maintain a very consistent panda-bear shape.”

Elsewhere, an extremely wealthy woman (Swoosie Kurtz) is seen as something of the economic flipside to the grandparents in Charlie and the Chocolate Factory, spending her entire life in bed in an exaggerated display of idle wealth. Her only pleasures consist of sitting up and watching television, not unlike David Bowie’s detached alien in Nicolas Roeg’s The Man Who Fell to Earth. In one of the funniest and most satirically pointed subplots, a couple (Spalding Gray and Annie McEnroe) enjoy a long-lasting, comfortable marriage predicated on never speaking to each other, resorting to using their children as proxy interlocutors at the dinner table. Everyone has a cartoonish personality quirk, but the actors portray these characters with an unpretentious openness that renders them unexpectedly relatable.

Likewise, the film’s depiction of Americana at the onset of globalizing capitalism presents a Tati-esque vision of cultural homogenization that nonetheless feels like an honest tribute to the drab surroundings of much of the country’s small towns. Shopping malls, box-like office buildings, and metal warehouses conspicuously dot an otherwise gorgeous landscape, but these edifices are as crucial to the identity of Virgil as the surrounding widescreen vistas. As shot by Ed Lachman, True Stories balances worn, realistic looking neighborhoods with vivid splashes of color that deepen the off-kilter nature of the film’s setting and people, stressing that both sprang out of Byrne’s head and reflect his skewed perception of the world.

With no overriding structure to make sense of Byrne’s rambling, impressionistic view of Virgil, True Stories moves in unpredictable patterns, jutting from gorgeous neo-western landscapes to non-sequitur gags on the fly. Often, the two combine, as in a lovely shot of a couple walking off into the sunset as purple clouds hang low over the frame, leaving only a sliver of fading sunlight in the vanishing point. As the pair continues to recede from the camera, the woman suddenly asks, “Did you fart?”

In one scene, Gray’s businessman abruptly launches into a monologue about how semiconductor design is a microcosm for shifting human attitudes toward work—his rapturous libertarian vision of a world where “there’s no concept of weekends anymore” eerily prophesying the tech industry’s impact on labor. The delicate tonal balance that Byrne achieves between irony, eccentricity, and tenderness presages the lightest moments of Twin Peaks, a wild but nonetheless keenly observant work of comic anthropology.

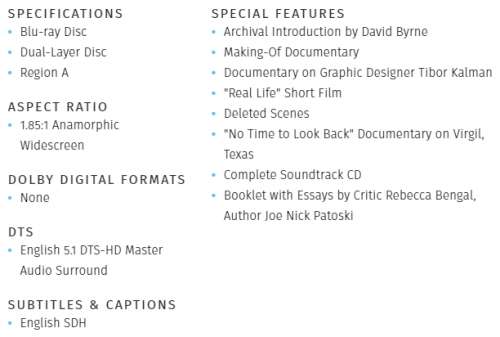

Image/Sound

True Stories looks resplendent on Criterion's restored transfer, which emphasizes the heavy color saturation of Ed Lachman's cinematography. The hyperreal blues of the rear-projected skies and primary-color tints of the musical scenes pop with intensity and depth, and facial textures are so clear that they add to the film's artificial vibe. And yet, the image retains a healthy layer of grain throughout, indicating a lack of over-aggressive digital cleanup. The audio track is faultless, with all dialogue clear in the front channel and effects evenly distributed in the surrounding speakers. Talking Heads fans can rejoice in the careful surround mixing of the soundtrack, which cleanly separates the elements of the band's funk-country new wave songs to make it easier to pore over the nuances of the group's compositions.

Extras

A 30-second archival introduction by David Byrne does a surprisingly good job of setting up a musical frame of reference for viewing the film, but a new, hour-long making-of documentary truly dives deep into Byrne's inspiration for the film and the way his collaborators helped him to adapt it for the screen. An older documentary made during the film's production covers some of the same material but offers a more immediate sense of the filmmakers grasping the idiosyncratic contours of the project without the benefit of hindsight.

A brief documentary covers the work of late graphic designer Tibor Kalman on the Talking Heads's videos as well as True Stories, while a retrospective faux-doc titled "No Time to Look Back" returns to the film's shooting locations to imagine how Virgil has changed over the years. There's also a bunch of deleted scenes that are easy to imagine effortlessly slipping into True Stories, given the film's loose and dreamy structure.

But the biggest draw of this release may be the CD of the film's complete soundtrack, which marks the first time it will be released as it appears in True Stories. Finally, the disc's accompanying booklet contains a host of essays, including a general review by critic Rebecca Bengal, a piece by Texan author Joe Nick Patoski on the True Stories's depiction of Texas, reflections on some of the film's recurring motifs, and an archival piece by Spalding Gray that details how he came to collaborate with Byrne.

Overall

David Byrne's affectionate comedy of funhouse Americana is one of the most ahead-of-its-time films of the 1980s. Its unique beauty is perfectly preserved on the Criterion Collection's new release, which comes with the excellent bonus of a CD containing the film's complete soundtrack.