Whether it’s a Desert Island or elsewhere, the best radio puts you in the picture

Via The Telegraph

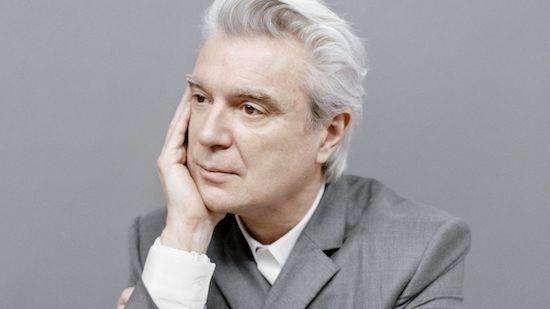

Photo by Jody Rogac

By Jemima Lewis

If I had to choose one radio programme to take with me to a desert island it would, of course, be Desert Island Discs (Radio 4, Sunday). Even on a bad week, it’s good. Worst-case scenario, the guest is a prickly, humourless bore – in which case, how fascinating! Or their music choices are hopelessly naff – in which case, how fascinating!

But the programme is enjoying a golden streak at the moment. Last week’s interview with the philosopher John Gray (still available on iPlayer) felt like a blast of cool intellectual air, much needed in the current fetid political atmosphere. This week’s episode was even more enjoyable, and not just because it featured one of my all-time pop heroes.

David Byrne is the former frontman, and driving force, of Talking Heads – the post-punk, new wave band evocatively described by Kirsty Young as “ambiguous and twitching”. Like so many of the best pop groups, Talking Heads was formed by a group of art-school friends. They were self-consciously avant-garde, even by the standards of Seventies New York. Chuckling at his own bravado, Byrne told Young how the band “set out to reinvent everything from scratch”. They banned themselves from striking “rock and roll poses” or indulging in “long, noodly guitar solos”, and – perhaps most rebellious of all – resolved to “dress like normal people”.

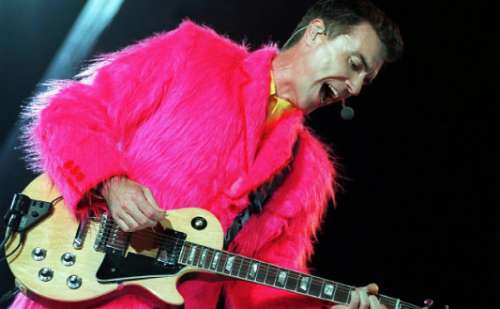

But Byrne couldn’t look like a normal person if he tried – and he never really did. The “everyman suit” he most famously chose to wear on stage was gigantic and almost perfectly square, so that his lanky neck protruded from it like a worm wriggling out of a box. He didn’t so much dance as convulse rhythmically, wibbling his arms and legs around, juddering on the spot, staggering about the stage as if he’d been shot, and sometimes lying on the floor, spasming gently.

“Do you believe, I wonder,” asked Young with delicious tact, “in such a thing as pretentiousness?” “Yes,” replied Byrne cheerfully. “It gets a bad rap… The best part of pretentiousness is just feeling free to try something else.” Byrne’s music choices reflected this freedom, ranging from a Scottish folk song (a tribute to his Glaswegian parents) to a Brazilian art house track featuring power tools and the clacking of typewriter keys.

The only duff moment was when Young tried to coax Byrne into voicing a platitude. Asking what he considered his greatest achievement, she hinted heavily, “I’m thinking about your role as a parent.” “Yeah, that’s what everybody would say though,” he groaned, quite rightly. “That’s such a clichéd thing.” In the same spirit of anti-schmaltz, I loved his confession – complete with the sound effects of reluctance – that he found the child-rearing years a struggle. “I did it. But at the same time – nnnnnn! – it was like – nngrrrrrr! – grit your teeth and push the pram.”

The dreaded pram in the hall also loomed large in Perfect Husband, Pitiable Artist (Radio 4, Tuesday), in which the pianist Lucy Parham considered the difficulties of combining artistic freedom with domesticity. As evidence for the prosecution, she presented the wicked life of the French composer Claude Debussy.

A funny-looking cove with a flat head and bulging brow – imagine the actor Toby Jones, if someone had dropped a large weight on him – Debussy nonetheless had an electrifying effect on the ladies. At 18, he began an affair with a 32-year-old married woman. After that, he cantered from one lover to the next, strewing broken hearts behind him. Debussy’s first wife, Lilly, was so devastated when he abandoned her that she shot herself in the chest with a revolver. She survived, but the bullet lodged permanently in her spine. It was, she later told friends, all she had left of her marriage.

It’s a terrific story – but, alas, not told well. Parham’s narrative was constantly interrupted by the musings of two other contributors (the novelist Sebastian Faulks and the singer-songwriter Laetitia Sadier), making it unnecessarily confusing. Neither did the programme prove, or disprove, its central premise. Does being a perfect husband make you a pitiable artist, as Debussy suggested? Or is this old trope just an excuse for bad behaviour?

Altogether more skilfully done was The Expressing Room (Radio 4, Monday), Fi Glover’s moving dispatch from the Evelina London Children’s Hospital. An expressing room is where mothers go to pump breast milk for their very sick babies. Glover perfectly captured its strange atmosphere: the continual whirr of the pumps; the mothers lined up, as one observed, like cows in a milking parlour; the weight of sorrow in the air. “Very few people ever come to a place like this,” Glover observed – but the best radio, like this, puts you right in the room.