A Society in Miniature

| February 9, 2017

I caught the big Robert Rauschenberg show at the Tate a couple of months ago. I knew Bob; as some may already know, he did a record cover for Talking Heads in the mid-'80s.

Here’s how that happened

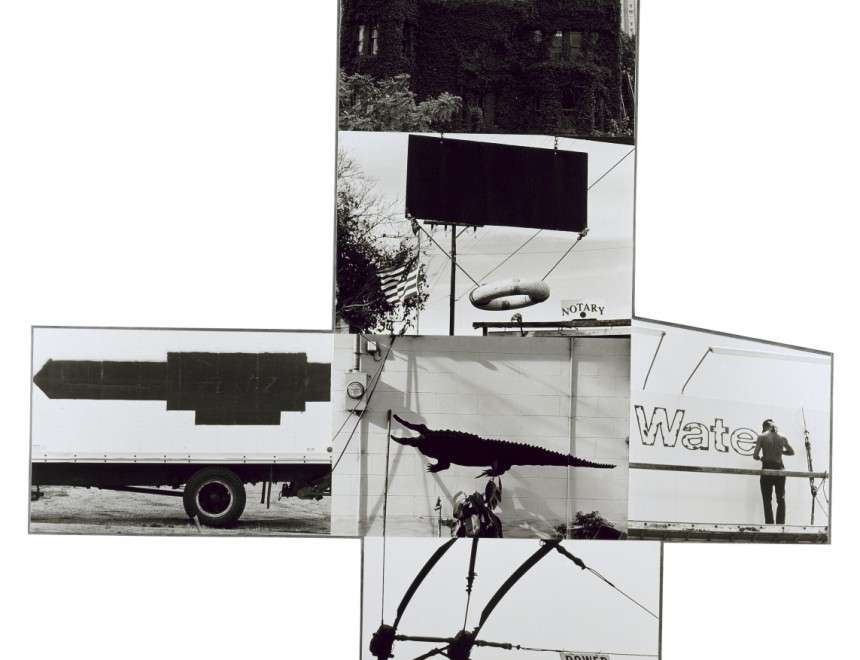

In the early '80s I’d seen a show of his B&W photos juxtaposed with one another at Castelli gallery in Soho. In these photo collages (he called them Photems) there were no drips, smears overlays or any other “painterly” techniques. I loved them. Although they were black and white, I thought they were pretty trippy—the ordinary objects he’d photographed looked strange and new.

Image: Photem 28

Maybe it was this strange and new quality that resonated for me; the interplay between the images seemed almost musical. Shapes seemed to echo and resonate with each other: a coiled garden hose and a rusted road sign, the parallel staves of a clothesline and a series of skid marks on a road. The images existed in a simultaneous place—all of them equal—like the sounds and voices in a piece of music or a recording.

It was also plain what was going on; there was no trickery. It was instantly apparent that this was a group of individual photos simply mounted alongside one another. There was no Photoshop or darkroom magic at work, and yet, the brain (mine anyway) still saw the photos intruding on one another. It was like a magician doing a trick and showing how it was done at the same time, and yet, despite knowing how it works, it continues to work on the audience. The Tim Noble and Sue Webster shadow pieces do the same thing.

I’d been a fan of RRs work for ages (I went to art school, after all), and I’d grown up in an era when artists often did amazing record covers for popular musicians, so I thought “Why not approach Bob about doing a cover for the next Talking Heads record?” Bob said “Yes”, but he wanted to do something unusual, he had an idea of something that deconstructed the idea of what a printed record sleeve might be. I wouldn’t have expected anything less; of course he’d question the very idea of what a record package could be. And why not question? That’s why one would approach an innovative artist after all—certainly not to get a reproduction of one of their paintings on a cover.

Anyway, that cover is a story unto itself, some of which is told over at Artsy.net.

How does one learn to think different?

The Tate show is wonderful, even if it only covers a smattering of Bob’s prodigious output. The curator, Achim Borchardt-Hume, met my friend and I, and we began to ask about the place where Bob spent some of his formative years, Black Mountain College, in western North Carolina, near Asheville. We were curious what sort of place would nurture the innovation and free thinking of someone like Bob, as well as that of host of other writers, artists, architects, composers and choreographers who passed through that place. Ultimately one wants to know, can that spark be re-ignited, in a contemporary way?

That tiny place in Asheville North Carolina seemed to possess some magic ingredient during its relatively short life—pre- and post-WWII—that produced an incredible number of ground-breaking creators in a wide range of fields. It almost seemed as if everyone who was touched by that place, by their experience there, went on to a have a major impact in the 20th century, and beyond.

It was established in 1933, during the depths of the economic depression, and by the time the war was in full swing the faculty included an amazing group of people. Here is a partial list: Josef and Anni Albers, he a teacher and artist from the Bauhaus in Germany, she a textile artist; Walter Gropius, the innovative German modernist architect; painter Jacob Lawrence; the painters Elaine and Willem de Kooning and Robert Motherwell; Alfred Kazin, the writer; Buckminster Fuller the writer and architect—he made his dome there in ‘48; Paul Goodman, the playwright and social critic and poet Charles Olson. Poet William Carlos Williams and even Albert Einstein eventually joined the staff, as well.

The students were a hugely influential and innovative bunch, too. As word spread others visited there during their summer sessions to create new work—in 1952, John Cage came down and staged his first "happening" here while students Rauschenberg and Merce Cunningham assisted him with what later became known as performance art. There were painters Cy Twombly, Kenneth Noland, Dorothea Rockburne, Ben Shahn, Franz Kline, film director (Bonnie and Clyde!) Arthur Penn, writer Francine du Plessix Gray and poet Robert Creeley.

What kind of place could attract and nurture this diverse group of people?

One can’t help but wonder if there was a formula and if the kind of radical innovation that happened there and that was carried out into the world can be repeated. What was that formula? Was it the teachers? The location? The philosophy? The students—the self-selected types who opted to try that kind of experiment?

Here are the basics of the school’s philosophy. John Rice, the founder, believed that the arts are as important as academic subjects:

- There was less segregation between disciplines than what might find at a conventional school.

- There was also no separation between faculty and students; they ate together and mingled freely.

- There were no grades.

- One didn’t have to attend classes. During break sessions the faculty trusted the students, and, as a result—without the top down rules—the students worked harder than during normal class times.

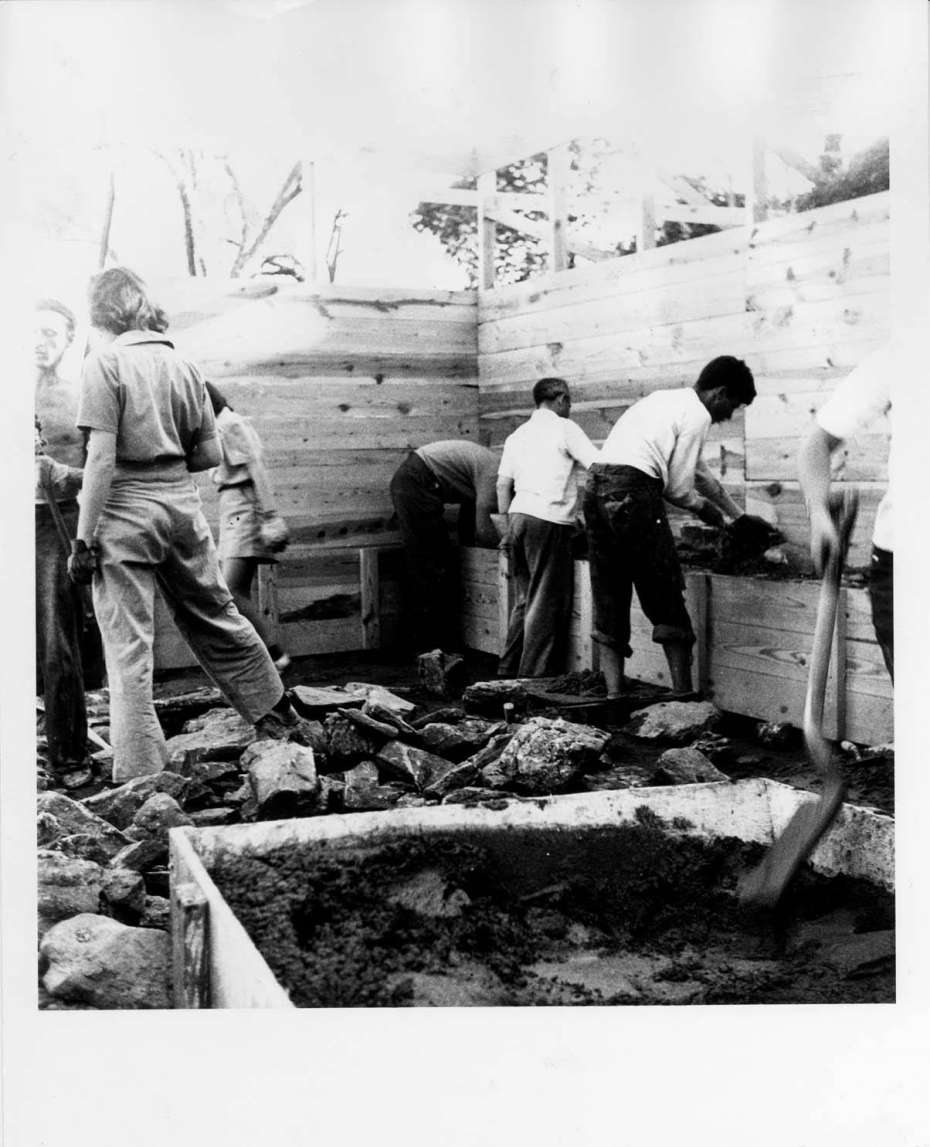

- Here’s what now seems like a really radical idea—manual labor (gardening, construction, etc) was also key. Try that at Harvard!. No one had outside jobs; they they all chipped in to build the actual school and to help serving meals or doing maintenance. The schools finances were somewhat precarious, so this was an practical economical measure as well as being philosophical. In order to allow for these daytime activities and work, classes were often scheduled at night!

Image: students helping build new buildings

A Society in Miniature—Created by its Members

It was also believed that the school community should be a kind of miniature society and to that end it should be democratic and communal. Students were on the school board and they chimed in on hiring and all the other decisions. All of these things—the work, play and learning balance, the non separation of disciplines and the self determination—were believed by the founders to be equally important. Students, Rice believed, learned better through experience than from the passing on of rote information. It was not a top down kind of education—it was non-hierarchical in that sense—and one was encouraged to discover things for oneself. Not all students are cut out for this (some kids do need discipline!), but the ones that did thrived. Needless to say, that also meant that as a result collaboration, experimentation and work across disciplines was all encouraged. The idea was less to turn out clever academics, but rather to help students find themselves and become a “complete person”. You weren’t learning a trade, but learning how to think, how to collaborate and cooperate.

The overarching theme as I see it (but maybe not explicitly expressed) is that students—with the help of the faculty—were here to create a kind of society in miniature. THIS was the deep and rich experience that they would take with them—something far more profound than specific lessons in creative writing, engineering or color theory.

I asked the curator, Achim, if these new ideas about progressive education and their implementation were what was primarily responsible for the explosion of creativity in this tiny school. He said, yes, those factors were influential, but just as much were other factors—the fact that many of the faculty were refugees (those pesky immigrants!) from the rise of nationalism and intolerance going on in Europe at the time. So you had this influx of some of the best and the brightest. The little college reached out for talent and they came to this little tolerant oasis in the Smoky Mountains. Oddly they did not end up at the big name universities—they gravitated to the mountains of North Carolina. (Though later some did end up at Yale and elsewhere.)

Rice himself asked Josef Albers to create the arts curriculum (though Philip Johnson made the recommendation), as the Bauhaus was being shuttered as Nazi influence grew across Germany. Albers was key in mixing disciplines in the arts department; there was little distinction made between fine and decorative arts (Ani Albers made nice rugs), as well none between architecture, theater, music, dance and writing. A writer in the literature deparment developed the pottery program. I personally find Albers artwork boring, but as pedagogical aids (and demonstrations of how our eyes and brains work) they are gorgeous. There’s an interactive tablet app version of his course available now—lots of fun.

Rauschenberg was very receptive to Werklehre, Albers's teaching method that incorporated design elements. In his teaching, Alber used various non-traditional art materials like paper, wire, rocks and wood to demonstrate the possibilities and limits of those various materials. He would have his students fold paper into sculptures so that they might understand the three dimensional properties of what is ordinarily seen as two dimensional. He had them solve color problems by devising situations in which colors are perceived differently in different environments. For a comparison, this was not about learning oil painting techniques

Bob hated Albers—he was too didactic for Bob’s freewheeling sensibility. But to his credit, Albers realized his limitations and brought in others who were very different in sensibility than he and his wife. He allowed for difference. Bob too adapted, he recognized the value of the discipline that Albers espoused.

Achim pointed out that these innovative artists allowed the Black Mountain students to experience the most innovative ideas that had been emerging in Europe firsthand (see learning by experience above). They were getting this stuff before many others and in a more visceral way. Intolerance was draining the sources of innovation from large parts of Europe and they would find roots in this odd corner of the New World.

The place Asheville was and still is an island of open mindedness and tolerance in a state that is fairly conservative. Other southern colleges were still quite segregated, but Black Mountain bravely bucked that tradition. They admitted Alma Stone Williams, the first black student to attend an all white educational institution in the South. I’m going to propose that the atmosphere in Asheville might have helped to allow these things to happen; in other southern towns Ms. Williams would have been hounded and possibly driven out. (That said, some of the locals thought the school as all about wild behavior and orgies.) The school wanted to bring the (NY-based black) painter Jacob Lawrence to visit, but busses, as we know, were segregated at the time, so they had a car drive him all the way down from NY. Homosexuality was tolerated there, as well, which, given that word of this tolerance might have gotten out, all of this may have encouraged young men who didn’t fit in to attend this college—a place where they wouldn’t be viewed simply as perverts and freaks. In this too I’d argue that Asheville had a tolerant hand.

Bob continued to be active post Black Mountain, and, though we might consider the idea naive, he believed in the power of art to bring people together. His series of international collaborations—ROCI—produced some wonderful work, but maybe just as important, his presence in many countries kick started a whole generation of younger artists in those places around the world.

Is This a Model for Today?

Are you kidding? Yes, in all ways—in the collaborations and the innovative work, in the tolerance and welcoming of the persecuted and unappreciated. We need to look to this place and time as a model for today—and boy do we need it now more than ever!

Why should we emulate this? Well, because it works! The ideas that flowed out of this place changed the course of 20th century innovation in a wide range of fields, and the influence is still being felt. Innovation, we should realize by now, is more valuable as a long term resource than the oil in the ground or the coal in the hills. Those will be gone or they will kill us, but if we can foster innovation we have a chance. One needn’t make work that resembles what was done there or was done later by those same artists. The ideas can be applied to all sorts of disciplines. The most profound influences to be gleaned are in form and in process—not in specifics. You may never ever want to listen to any of Cage’s music (though his early prepared piano pieces are actually quite beautiful), but his ideas and the joyous way he presented them are still influencing folks who aren’t even aware they are influenced.

The same is true with Bob—you may not love all or any of his work, but the pure pleasure of his innovations and the implications of his openness for the larger society are more relevant than ever.