A Taste of the Chennai Music Festival

| February 1, 2019

After about a year of being on my own music tour I decided to stay in motion. Sometimes stopping cold turkey can be a bit of shock. So, in mid-December I flew to India and attended a few days of the Chennai Music Festival—also known as the December Season. It’s been going on every year for a long time; Yale from Luaka Bop and I poked in to catch part of a performance at least a decade ago when we were there working on the Vijaya Anand record.

The festival is mostly Carnatic (South Indian) music and it takes place in at least 10 small and medium size auditoriums all over town: some are on university campuses, some are part of religious organizations, some are in cultural institutions and some are even in tents. Most of the shows are free. Sometimes there is food and chai available between performances—very good food I might add. The daily schedule of shows starts around 9AM (when else would a morning raga be appropriate?) and the daily run ends around 9PM. Every day, all month. That’s a lot of music.

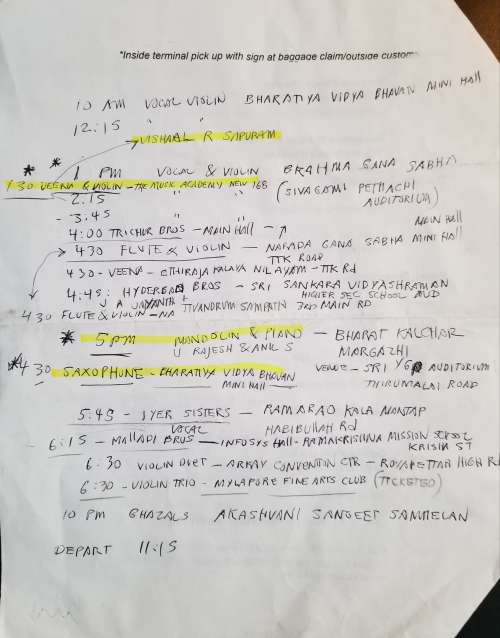

I didn’t manage to do 12 hours of music every day, but I did my best; one nice thing about performance in Asia is that audience members often come and go during the shows. They don’t chat, but there is an ebb and flow. Some shows were MUCH more popular than others. I could never figure out why, but then I am not an expert on this kind of music. I’d decide what to go to by looking at programs in the newspaper or an online newspaper and then I’d pick out some shows that seemed interesting to me. I wanted to see and hear the traditional performers, but I noticed there were quite a few in which performers were playing carnatic music on unexpected instruments. Here is a paper where I am trying to work out how to catch the maximum number of interesting (to me) performances in one day.

I used Uber cars or auto rickshaws to get me from one venue to the next. Ubers I used not for the comfort but because describing locations accurately with all the language issues (though English is spoken a little by a lot of folks in these big cities) sometimes became tricky. I was in Kochi on the west coast a few days before arriving in Chennai and there I had a bike to get around, but Chennai is much bigger and the traffic is crazy.

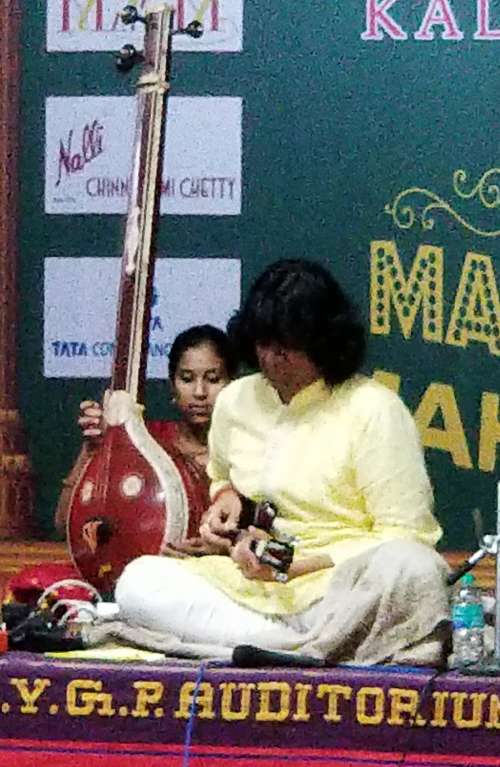

The music follows strict formats—the raga (scale), rhythm and mode are all predetermined, as well as the structure, but within those formats there is much improvisation. Some of the playing and singing is virtuosic and some have an aim to use their skills to add to the emotional poignancy of the melody. Most of the groups were made up of almost identical lineups: a tambora or two to provide the drone, often a violin or other melodic instrument to provide counter melodies to the vocalist or solist and some drums—most often a double headed mridangam drum and sometimes also a tabla player.

In the photo above the singer seems to have a little radio in front of her. I’m pretty sure it’s an electronic tanpura—an electronic version of the drone instrument. So she’s helping herself to stay on pitch by augmenting the drone provided by the real tanpura.

There were dance groups too, but most of the performances were vocal or instrumental.

What Are the Vocalists Singing About?

Most of the texts are religious odes to gods or goddesses, but as with the Old Testament Song of Songs, an ode to Shiva can sound awfully close to a very sexy love song—the same passions, intensity and feeling of surrender are evoked, in the same way that gospel music and RnB are very much overlapping. These are songs of passion and love. In Hindu mythology, descriptions and images of physical and sexual love between the gods and goddesses is not shunned. Westerners might find some of the images on the temples shocking to be seen in a religious context, but it’s all in the web of life and spirit—nothing, in this view, should be excluded.

From a temple frieze in South India.There’s a veena player in the bedroom! He’s blue… it might be Krishna?

Interplay and Improvisation

The very first show I saw when I arrived in Chennai involved a lot of interplay between the singer and the musicians. While singing, this first vocalist I saw would often wave his hand, gently, as if drawing the phrase he was singing in the air. In later performances I saw that the female singers or soloists did the same thing. The accompanying violinist, as appeared to be typical in carnatic music, would mimic their vocal phrases, but not always note for note—sometimes the violinist would further elaborate on the original phrase and sometimes the violinist or the drummer got to take a solo.

The drummer would both keep the groove going and add some fills. What was cool was how the singer would often cue the drummers, their hand delineating the fills and flourishes they should follow—again, drawing the phrase in the air—which, amazingly, the drummer would follow without fail. Everyone, except the poor tambora players—who it seems are about to get replaced by machines—got their solo moments.

The female violinist above was similarly signaled. As an audience member, I could see the singer's hand in motion. The violinist and the singer often did some back and forth, trading phrases, and, as with flamenco artists, if the violinist did something extraordinary the singer would wave a hand towards her or even add an “olé” type vocal expression of approval.

Pictured above is another violinist… Scarjo is moonlighting as a carnatic fiddle player, who knew? The vocalist sisters she’s playing with were very popular; all seats were taken, so us late arrivals were offered to sit on the side of the stage! The sisters, who are on this month’s radio playlist, would occasionally sing very convoluted melodic lines in perfect unison. The unison made me realize that what I might have often assumed was improvised embellishment was all very much a strict melody. And, as when harmonies and multiple singers sing a chorus in a western pop song, that line becomes a hook, instantly memorable. The violinists, in response, would often ease into riffs that echoed the vocal melody—by effectively fading in they would often overlap the singer or other soloist, emerging out of the tail of the main performers lick, rising up with their echo, and then fading away when the soloist entered again.

The drummers often seemed to be having a wonderful time. They’d glance at the singer, who is in effect the conductor, the young violinist sometimes smiled—all seemed to be enjoying the interplay and revelling and enjoying the moments of unexpected beauty or virtuosity. It was OK to show that you were having fun.

Pantomime and Mugging and Storytelling

Some of the performances involved storytelling. Above is a photo of a dance performance that was lovely, but devolved into what I would personally judge to be unacceptable mugging.

Another storytelling performance I saw involved a more traditional vocal group, but in their case rather than singing together all the time there was a bit more theatrical drama. The main singer would sing and then tell a bit of a story in character, and the other singers and musicians would then respond as other characters in the story, and then, after describing the episode having been described in dialogue, facial expression and gesture, they’d launch into another brief musical interlude.

Here’s a brief video of some of the storytelling parts:

Their set was like a hip hop album, only with longer skits and interludes than songs, and all the interludes thematically linked to tell one longer story. Cool idea, eh?

Any Instrument Can Be A Carnatic Instrument

As anyone who checks out the accompanying playlist will notice, quite a few instrumentalists played what seemed to me, to be unexpected instruments—well, unexpected to me for this music.

A young man (he seemed to me to be in his teens) came on stage in a silver brocade jacket and played carnatic melodies that grooved in an unexpectedly funky way. (I have a different sax player on the playlist; there’s more than one!)

Young virtuosos were prized. Here is a VERY young girl playing a set on the veena—her instrument is larger than she is! She was pretty good! Well, to my untrained ears.

On another stage the soloist played a chitraveena (basically a veena played with a bottleneck)—carnatic Delta blues! Ry Cooder check this out. Very cool swoops, growls and licks. I was blown away by this set.

Another night I caught a carnatic electric mandolin artiste…

Srinivas was the most famous Carnatic mandolin player in India. The musician I saw plugged in and added some reverb and was accompanied by a pianist who took on the violinist role. It bordered on New Age music to my ears, but then sometimes it went somewhere completely psychedelic, which was a bit of a head twister. There’s an example on the playlist—you may not recognize it as a mandolin, but here is a short video:

I don’t think I ever dozed off, which might be a surprise, as we Westerners tend to associate much Indian music with meditation and a calm sense of spirituality. Although the songs often have spiritual themes, the vibe (though not the actual music) is more akin to jazz or flamenco. John Coltrane and Pharoah Sanders certainly saw their music as an expression of deep spirituality, but, like their music, Carnatic music is hardly soporific.

In my all too brief visit, I only touched the surface; the festival goes on for a whole month. I was tempted to buy one of these Carnatic players for deep immersion—a kind of digital boom box pre-loaded with 5,000 musical favorites.