Democracy — What Would That Be Like?

| March 20, 2019

_930_698_60.jpeg)

Nuit Debout protesters participating in a direct vote in Paris, 2016. (Courtesy Wikipedia Commons)

Our system—as evidenced by studies at Princeton University and Northwestern University and other research—is not a true representative government. The will of the majority of people in the US is not represented—except in those cases when the desires of the majority match the policies favored by the wealthy and powerful. Their interests are more often enacted into law. We, therefore, do NOT live in a democracy.

As Tim Wu points out in the New York Times, the wishes of the majority are often all but ignored:

About 75 percent of Americans favor higher taxes for the ultrawealthy. The idea of a federal law that would guarantee paid maternity leave attracts 67 percent support. Eighty-three percent favor strong net neutrality rules for broadband, and more than 60 percent want stronger privacy laws. Seventy-one percent think we should be able to buy drugs imported from Canada, and 92 percent want Medicare to negotiate for lower drug prices. The list goes on.

But, if we could live in a democracy, what would it be like?

I saw Astra Taylor’s documentary What Is Democracy? recently, and it got me thinking—which is what this film is meant to do. It’s not a movie that hands out answers, and it never mentions "Individual 1". I’m not an expert on any of this, but especially considering the times we live in, I have taken an amateur’s passionate interest in wondering what this thing we claim to love so much really is.

Cornel West was at the screening (he also appears in the film), and he made the point that democracy alone is not going to solve our problems or lead to some of the big changes that are needed in the US or other countries. Brown v. Board of Education, the Civil Rights Act and Women’s Suffrage did not happen because they were put to a vote. In fact, West pointed out, if some of these things had been put to a vote, they probably would have been rejected. The voice of the people—which is heard via voting—needs to be coupled and linked with other institutions for the whole thing to work. The rule of law, a drive for justice, a free press…I would also venture to say that if there’s too much economic inequality, you can’t have democracy as well. In such situations, democracy is not possible.

Mob Rule

Democracy—as Plato and Alexis de Tocqueville both point out—is, in its ideal form, rule by the majority, which is a kind of mob rule. This is sort of West’s argument also—the majority of people are not always fair or just, and their tendencies to ride roughshod over justice need to be tempered by other institutions. To do this, many constitutions have added articles to correct for the craziness of crowds—who tend to vote only according to what they think is good for them.

I saw the TV series with Morgan Freeman called The Story of Us, and in it, President Bill Clinton tells him that in 1995 the Mexican peso was on the verge of collapse, which would have caused pain and suffering well beyond Mexico. He says 80 percent of the US was against giving Mexico a loan, but he did it anyway. Mexico later paid it back, and thus, he claims, they averted a disaster. He gives a couple more examples to make the point that sometimes an elected official should act against the will of the people…and that they empower him or her to do so.

Hmmm, OK, but not everything Clinton did ended up being good for us… So what about that stuff?

As a counter to the undue influence of the majority, the electoral college was, among other things, supposed to tilt the playing field so the more populous eastern states could not enact legislation harmful to the less populous rural South and West. It was about having less direct representation and, at the time, more fairness—at the time. The price of protecting this rural minority was that they would always have more power than the increasingly urban majority. Lots of folks now argue that the electoral college has outlived any usefulness it might have had, as witnessed by the election of 2016 when Donald Trump lost the popular vote by a large margin. The electoral votes that the less populous states possess give those areas an advantage—one that the GOP has made use of. As a result, a minority can take over the government.

A majority of folks in the US want stricter gun control, as well as some free college education, but with the power in the hands of the few, their will is blocked.

Sometimes we intentionally tilt toward the rights of a minority. We accept that sometimes fairness and justice should override the majority’s voice. Theoretically, the courts can make decisions—as in the case of Brown v. Board of Education or Women’s Suffrage—that enact just rulings and express the presumed values inherent to the nation and its constitution, but they do not always express the will of most people. This balance between representation and justice requires constant tinkering.

Other factors like gerrymandering and voter suppression—both of which have gotten completely out of hand—skew things toward the will of a minority. Some states have restricted gerrymandering, and others have proposed laws to make it illegal. Voter suppression, a legacy of Jim Crow, keeps popping up; eliminating it is like a game of whack-a-mole, as new tricks keep getting invented.

Justice and Rule of Law

As important as it is to give the population a voice through voting, it must be coupled with other institutions—such as the courts and the rule of law—to guarantee that things don’t spin out of control. Voting is not enough. We’ve all seen those glowing media reports about people voting in Afghanistan or Iraq and the smiling Americans congratulating themselves on spreading democracy. Well, voting ain’t democracy… Or, if that’s all it takes, then democracy is not what it’s cracked up to be.

Some of this might be obvious to folks from what they’ve learned in school, but bear with me… I need to lay it all out for myself to be able to try to understand where we’re at.

Laws have to be enforced for the system to work. If—due to corruption or bias—the laws are not enforced, we lose trust in the government. That is happening now. Sometimes those whose duty it is to administer the rules take the law into their own hands. That is happening now too.

In certain cases, breaking or not enforcing a law seems like the right thing to do. Rosa Parks, for one, disobeyed a ridiculous local law. Those who participated in the Greensboro lunch counter sit-ins opposed another. Could one make the same argument about the Bundy family and their claim to federal lands? Does each aspect—representation, the press, rule by law—need to be tempered by the other…?

The undeniable significance of the free press in Democracy.

The Fourth Estate

A vibrant and free press (which we are in danger of losing) keeps our representatives honest, or it tries to. It also makes it possible to have an educated citizenry, knowledgeable about what is happening in their community, their country and the world at large. Without information, we are vulnerable to manipulation. “Democracy Dies in Darkness” is the Washington Post slogan.

Issues of fake news and the partisan press aside, truthful information and access to that information are essential. It becomes clearer and clearer that a functioning state is not about the simple idea of one man, one vote—that is far from enough to make a functioning system. As a young woman of color says in Taylor’s documentary, “We fought for the vote, a long hard struggle and it isn’t over, and somehow that still wasn’t enough… How much more do we have to do?”

Maybe there are structural problems in our form of government?

Representative John Dingell—the longest-serving representative in the US (who recently passed away)—suggests that it would be a good thing to abandon the Senate. The Senate, like the electoral college, is effectively governance by a minority. More and more people are feeling like the electoral college has seen its day, but why not the Senate too? More on Dingell’s ideas later.

Is There Another Way? Other Forms of Democracy

What we take to be democracy is not the only form that a representative government can take. In fact, what we have in the US is a far cry from democracy as it was originally conceived.

A Greek woman in What Is Democracy? points out that in Athens—the place that gave us this word—democracy was very, very different from how our system currently functions. For starters, women, slaves and foreigners couldn’t vote. Well, women here in the US couldn’t vote either until not so long ago, so let’s not feel too superior. And voter suppression is still rampant. To be fair, less than half of the population in Athens was engaged in decision-making. So, democracy didn’t really serve the will of all people. We, for example, have a representative democracy; the Athenian form was a mix of representative and direct democracy…but the representatives weren’t elected!

Scale may have been a factor in whether Athenian democracy worked well or not—Athens was a city-state, not a widespread country or empire. There were about 30,000 to 60,000 eligible (male) voters.

How Did It Work?

There were three principal layers to Athenian democracy: the law courts, the assembly and the boule. The jurors in the courts were chosen by a lottery—there were no judges!

There were also NO political parties. For me, that alone immediately is something I want to know more about. Here’s how it worked.

Ordinary men made up the assembly and would make all the most important decisions—like whether or not to go to war. They would gather on a hill in Athens called the Pnyx about once a month. There had to be approximately 6,000 jury members present at a meeting before they could decide anything. That’s a BIG group. Big as the audience at Radio City Music Hall. How in the world was that managed? How did they even hear one another? And why did they meet just once a month? That doesn’t leave much time for nuanced debate. I’d have to dig deeper to answer all these questions, but for now the point is that a large group of citizens made many of the important decisions.

Reenactment of an assembly in Athens.

The other institution that made up Athenian democracy was called the boule. The Athenians selected between 400 and 500 men every year to be in this group. So this was closer to representative democracy—but how they chose them was very different than our electoral process. They felt that using a lottery (more on that below) rather than electing their representatives was better. It left the choice of who would represent them in the hands of the gods, and the gods could make better decisions than men could. (The mercurial Greek gods? Really?)

The boule met more often than the assembly and decided things that weren’t as critical. It suggested new laws to the assembly, for example, and made sure they were being enforced. The boule also took care of things like repairing streets, fixing public stoas, temples and building ships for the Athenian navy. To me, it sounds like here there may have been room for debates on some of these issues… After all, there were hundreds of members who would have had a variety of opinions. I wonder how that worked.

The fact that these 400 to 500 representatives were chosen by a lottery is key. That means EVERYONE and ANYONE (well, yes, only men and not slaves or foreigners) had a chance of being a representative at some point in their lifetime. If not this year, then you might get picked next year. The people’s representatives could therefore not run for election or be supported in an election by special interests. No one knew who would get picked. My guess is that this made everyone, even those not currently serving as representatives, feel essential, responsible and engaged—as anyone could be a representative the following year.

Your crazy neighbor? Yup. That football player. The cab driver. The real estate developer—woops, we got that one already. Money used to influence candidates? Won’t happen in this system.

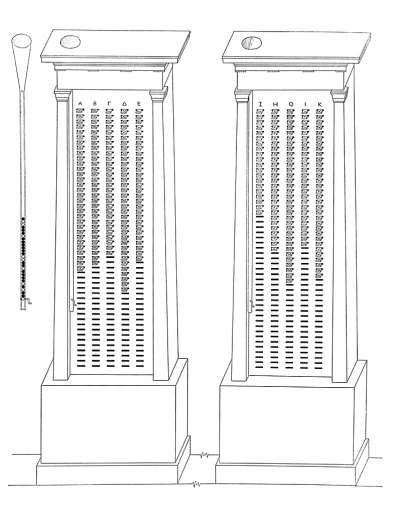

How did this lottery work? It’s pretty cool actually. They made a randomizing machine to make sure the lottery was truly in the hands of the gods.

What if you’re a farmer and it’s harvest time or planting time and you get called to serve in the boule? How were conflicts like that resolved? I do love the idea that folks from all walks of life—with the exception of women, slaves and foreigners—would get thrown together. A businessman, a musician and a farmer all repping side by side—it wasn’t a council of millionaires, as our Congress and Senate seem to mostly be today.

(Left) Rendering of a randomizing lottery machine. (Skidmore) (Right) Surviving portion of a randomizing lottery machine. (History Extra)

Civic Education

We often, echoing Thomas Jefferson, believe that only an informed citizenry can make intelligent decisions when it comes time to vote (see the section on the Fourth Estate above). The Athenians, however, were not all that well educated in the sense of book learning, but most of them could read and write, and they had civic education and skills that we seem to lack.

They developed this education and skills through a variety of communal institutions where ideas and structures of democratic citizenship could be spread, absorbed and put into practice. They organized annual, monthly and daily religious celebrations, as well as yearly drama festivals that were also often based around the mythologies of the Gods. Pretty much everyone participated in these. (Note: Voters were sometimes influenced by the political satire of the comic poets in these theatrical performances…just as many people today get their news from late-night comedians.)

Athenians directly engaged in politics at both the local (village, parish and ward) and city-state levels. They were involved in the military service, fighting against both Greek and non-Greek (especially Persian) enemies.

Formal Athenian democratic politics, moreover, didn’t distinguish between the executive, legislative and judicial branches or functions of government that are, today, part of what we feel are essential to a democracy. Rather, citizens ruled in all branches equally. Trials for alleged impiety were, properly speaking, political trials, as in the case of the persecution of Socrates.

We may feel that Socrates was convicted unjustly—what about free speech? We may ask—but it seems his conviction was the will of the people. It was decided that he was subverting both the state and religion.

So, some aspects of Athenian democracy raise more questions than answers—but, as a whole, I found this information surprising and inspiring. Does anything like that survive? Anything like this exist now?

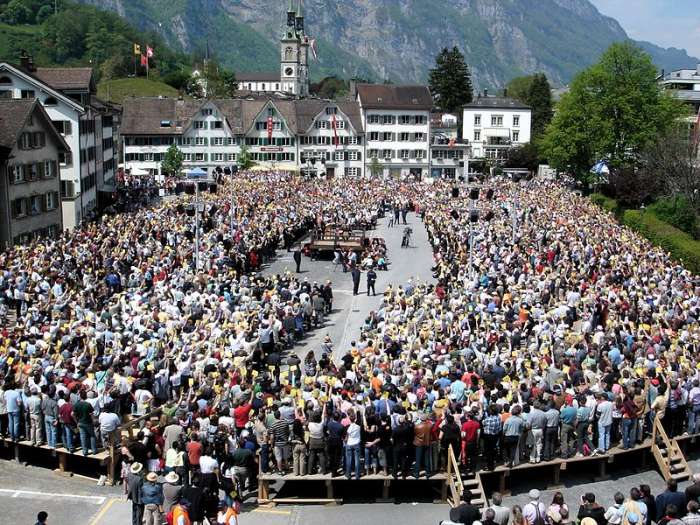

Residents take part in direct voting during a Landsgemeinde in Glarus, Switzerland, 2006. (Future Foreign Policy)

Direct Democracy in Switzerland

Switzerland is a country that has retained some elements of direct democracy. Anyone can propose a constitutional reform or referendum. They do have representatives, but fairly often, they propose and vote directly on issues large and small, local and national.

Swiss citizens vote regularly on various issues on every political level—from approving the construction of new schools and the building of a new streets to changing policies regarding sexual work, the constitution or the country’s foreign policy—up to four times a year.

Some Swiss cantons use direct democracy in the form of a Landsgemeinde, in which locals meet on a certain day in the open air to decide on specific issues. Voting is accomplished by those in favor of a motion raising their hands. So, this is really the will of the majority—the winner takes all.

Johann Jakob Mock, Die Landsgemeinde in Trogen Canton Appenzell, 1814. (Wikipedia)

Mexico: Chiapas and Michoacán

In Mexico there are communities—mainly dominated by indigenous peoples—that practice forms of direct democracy, including in areas controlled by the Zapatistas in Chiapas and in the state of Michoacán. It goes without saying that this means the often corrupt political parties of Mexico are excluded.

A similar self-governing structure has been instituted in Cherán, a small town in the state of Michoacán. (I’m writing a separate piece about their adventure with more details about how it works and how successful it’s been.) Basically, they also kicked out the corrupt police and party politicians, and though they interact with the national government they basically govern themselves and have control over their common resources.

To keep the political parties and cartels out, the citizens have armed themselves, which is a little scary, but one might (in a pinch) compare it to the American Revolution, where farmers and locals took up weapons against the British. But any armed insurrection—and there have been many in Latin America—can easily get out of hand.

Residents of Cherán, Mexico. (BBC)

So what are these other forms of democracy like? Well, we can’t ask the Greeks—that was a long time ago—but is there some way to determine whether they were satisfied with the system?

We can see how people in Switzerland and Mexico feel about how democracy operates in their societies. But are there “control” communities nearby that are similar except for their forms of governance? So we can see what a difference it makes?

Yes, in Mexico there are. Nearby towns and villages are overrun by the cartels, some of which are in league with the police and politicians—crime is rampant, and citizens are afraid to go out at night.

Although voting is no way to guarantee a functioning form of governance, it’s hard to evaluate its effects when people don’t vote or there is voter suppression as there is in the US. But what about when everyone at least votes?

In some countries, like Australia and Brazil, there is mandatory voting. In Australia, as one might expect, this has an effect on policy and decision-making. Disadvantaged and underrepresented groups get heard, and policy is impacted as a result. Though the effects are far from simple… Some people end up voting randomly, for example.

How is it enforced? They could take away your driver’s license if you don’t vote. And in some countries, they could also deny you a passport or a bank loan if you don’t participate.

In Brazil, enforcement is a problem—some folks just pay the fine and can’t be bothered to vote. But every little bit helps.

The late John Dingell, sworn into office by Sam Rayburn (John Dingell)

Three Suggested Fixes

Here again is the late John Dingell, the former representative who served in Congress longer than anyone else. This is a piece he wrote for The Atlantic. I have edited it a bit for brevity—the whole article is inspiring and is available online.

Just for a moment…let’s imagine the American system we might have if the better angels of our nature were to prevail.

Here, then, are some specific suggestions—and they are only just that, suggestions—for a framework that might help restore confidence and trust in our precious system of government…

1. The elimination of money in campaigns. Period. Elections, like military service, should be publicly funded. Each is an example of duty, honor, and service to country.

Public service should not be a commodity—and elected officials should not have to rent themselves out to the highest bidder in order to get into (or stay in) office. If you want to restore trust in government, remove the price tag…

2. The end of minority rule in our legislative and executive branches… The idea that Rhode Island needed two U.S. senators to protect itself from being bullied by Massachusetts emerged under a system that governed only 4 million Americans….

Today, in a nation of more than 325 million and 37 additional states, not only is that structure antiquated, it’s downright dangerous. California has almost 40 million people, while the 20 smallest states have a combined population totaling less than that. Yet because of an 18th-century political deal, those 20 states have 40 senators, while California has just two. These sparsely populated, usually conservative states can block legislation supported by a majority of the American people. That’s just plain crazy…

In primaries, the vocal rump of a minority of obnoxious asses can hold the entire country hostage to extremist views. This insanity has sent true public servants fleeing for the exits. The Electoral College has the same structural flaw. Along with 337 of my colleagues, I voted in 1969 to amend the Constitution to abolish it…

How do we fix this? Practically speaking, it will be very difficult, given the specific constitutional protection granted these small states to veto any threat to their outsize influence.

There is a solution, however, that could gain immediate popular support: Abolish the Senate… It will take a national movement—starting at the grassroots level—and will require massive organizing, strategic voting, and strong leadership over the course of a generation. But it has a nice ring to it, doesn’t it? “Abolish the Senate”…

3. The protection of an independent press.

The Fourth Estate is not a branch of government, but none of the branches of government can be trusted to function honestly without an unfettered free press vigilantly holding it accountable.

Thomas Jefferson: “Our liberty depends on the freedom of the press, and that cannot be limited without being lost…"

Since before the Civil War, we’ve been told that “Providence watches over fools, drunkards, and the United States.” Yet the good Lord also granted us free will. The direction we choose to follow is ours alone to make. We ask only that he guide our choice with his wisdom and his grace.

It’s up to you, my dear friends.