A BRILLIANT RETURN FOR A TALKING HEADS ALBUM

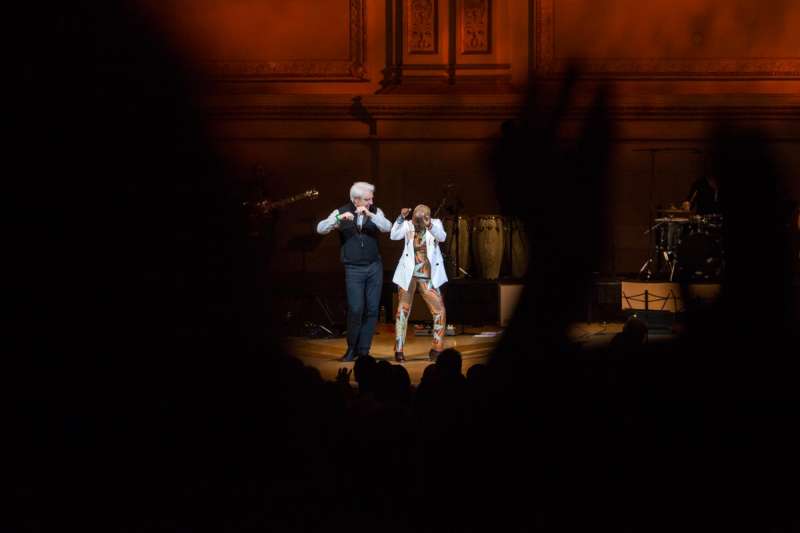

Onstage at Carnegie Hall, Angélique Kidjo wore a fresh pantsuit and an oversized white jacket, a sly reference to the big white suit that David Byrne wore in the “Stop Making Sense” concert film. Photo c/o: Caitlin Ochs

Written by Paul Ellie

Twenty-six years after Talking Heads broke up, David Byrne remains one of New York’s most recognizable people. There he is, about town, slim and white-haired—on his bicycle, at a just-opened restaurant, at the Public Theatre (his second musical, “Joan of Arc: Into the Fire,” had a run there last month), or at a concert by an artist on his boutique record label, Luaka Bop.

Before I took a seat at Carnegie Hall last Friday, then, I periscoped the room, wondering whether he was there and, if he was, whether he would wind up onstage. Angélique Kidjo, born in Benin, long based in Brooklyn, was performing “Remain in Light,” and it seemed inevitable that Byrne would show, if only to see what another great artist would do with his strongest, strangest work.

The band members strode out and took their places beneath the Stern Auditorium’s broad arch: a dozen musicians, female and male, black and white, singers and instrumentalists. Kidjo emerged stage right, wearing an extravagantly patterned pantsuit and matching headdress of African design. She sang a plaintive melody over lightly strummed guitar chords, folk-song-like. Then she called out, a cappella, “And the heat goes on . . . and the heat goes on”—establishing the call-and-response motif that is the key to her interpretation of “Remain in Light.”

“Remain in Light” is not Byrne’s work, of course. It’s Talking Heads’s work—the band’s fourth LP, released in October 1980. And yet the record prompted questions of origins and ownership, of influence and appropriation, even before it came out. Those questions make Kidjo’s decision to perform it in concert—two decades after Phish did so during a Halloween show, in Atlanta—as brilliant as it was apt. Here was a New Yorker expatriated from West Africa, revisiting a record thick with West African influences made by a distinctly New York band, and doing it in the midtown palace of Euro-American art music, with a lineup that made any idea that she was taking the music “back to Africa” reductive and cliché.

“And the heat goes on,” Kidjo, singing now, declaimed over a bass riff. So did four young singers at stage right; so did two older singers at stage left. One guitarist—Dominic James—played bright, reiterative figures in the style of Nigerian highlife; the other—Lionel Loueke—made piercing electric sounds. One drummer at a trap set and another on congas put their parts in easy synchrony. So the layered, textured, polyglot funk of the LP was layered and textured afresh.

“and the heat goes on” was a New York Post headline during a run of sultry weather in 1980. Byrne and the other Talking Heads—the guitarist and keyboardist Jerry Harrison, the bassist Tina Weymouth, the drummer Chris Frantz—had spent several weeks jamming in recording studios, swapping instruments and bringing in other musicians, such as the guitarist Adrian Belew, who had played with David Bowie and Frank Zappa. With the producer Brian Eno, they had taped several hours of grooves. Byrne needed vocals—lyrics and melodies. In early summer, he looked to the world around him; he listened to West African records he had come to know, especially those of Fela Kuti, the great Nigerian singer and bandleader. “And the heat goes on” became the refrain of “Born Under Punches.” “Born Under Punches” became a track on a record with the working title “Melody Attack.” “Melody Attack” became “Remain in Light.”

In August, 1980, Talking Heads played at Heatwave, a “new wave” rock festival outside Toronto, and there, before a crowd of a hundred thousand people (it was said), they were joined by one musician after another, until the band included nine performers. Four days later, the “expanded” Talking Heads played Wollman Rink, in Central Park, and photographs of a ten-piece Talking Heads appeared in the Times and elsewhere. There was Byrne alongside Nona Hendryx, known for her work with Labelle, and Jerry Harrison leaning over a Prophet-5 synthesizer next to Bernie Worrell, the keyboardist from Parliament-Funkadelic—white musicians and black musicians, side by side. Coming the month after the “Disco Sucks!” radio campaign—which culminated in the destruction of a crate of disco LPs between games of a Chicago White Sox double-header at Comiskey Park, in Chicago—this race-transcending arrangement was transgressive and revelatory.

Byrne, promoting the record up front, missed no chance to say so. He assembled a press release, setting out the record’s debts to West African music and citing John Miller Chernoff’s “African Rhythms and African Sensibility” and other texts. He spoke of the structure of the music, and of the band, as metaphors for a society in which many small parts contributed to a larger whole, rather than one characterized by individualism. (“In sacrificing our egos for mutual cooperation, we got something—dare I say it?—spiritual.”) Journalists took his prompt, referring to Fela, polyrhythms, and the African traditions of communal music-making in their articles and reviews.

Over time, stories of the vexed origins of “Remain in Light” gained traction. The record had followed on “My Life in the Bush of Ghosts,” a studio collaboration between Byrne and Eno, which was tied up in a legal dispute owing to their appropriation—sampling, we would call it now—of a broadcast by the radio evangelist Kathryn Kuhlman. “Remain in Light” had become an extension of that project and its recombinative studio process. “By the time they finished working together for three months, they were dressing like one another,” Weymouth said of Byrne and Eno. “They were like fourteen-year-old boys making an impression on each other.” They had cut and spliced the other band members’ parts, without asking. They had redone the songwriting credits to foreground their own contributions. As the touring band was put together, the inclusion of a second bassist, Busta Jones, left Weymouth feeling displaced. As for the African references, these were “nothing I had read and nothing that anybody had told me about during the performance of the record,” Frantz said. “There are African rhythms and African sensibilities in American pop music all the time, but I kind of resented not being informed that I was playing African rhythms until after the fact.”

Whose music was this? Was it Talking Heads music, or something else? The questions nearly broke up the band—and when Weymouth and Frantz’s side project, Tom Tom Club, caught on with black listeners (more than “Remain in Light” did), it was seen by some people as sweet revenge.

At Carnegie Hall, those controversies were thirty-seven years away. So was the question of American or African, made remote by the multinational band that Kidjo had assembled for the occasion. The guitarist Lionel Loueke, from Benin, studied on the Ivory Coast and in Paris before enrolling at the Berklee College of Music, in Boston, in 1999. The keyboardist Jason Lindner grew up in Bay Ridge and went to LaGuardia High School; the bassist Ben Zwerin (also a Berklee graduate) was raised in Paris, a son of the jazz critic for the International Herald Tribune. The Antibalas Horns—composed of members of the Brooklyn-based, Afrobeat-inspired outfit Antibalas—have played with Living Colour, Melissa Etheridge, the Duke Ellington Orchestra, and the “FELA!” pit band.

From the stage, Kidjo, who has served as a cultural ambassador for unicef and Oxfam, told the audience that she likes to “try to find a way to build bridges between cultures,” and explained that, for her, “Remain in Light” was such a bridge. Kidjo was born in Benin, in 1960; in 1983, already a working musician, she left the country, then under a communist dictatorship, and settled in Paris, where she first heard the Talking Heads album. “This album brought me back to Africa,” she said, recalling the powerful first impression it made: “ ‘This is African, yet it’s got something that is turning my head upside down.’ ”

She did “Listening Wind,” from the second side of “Remain in Light,” with Loueke suggesting the wind in the song’s lyrics through eerie electronic-guitar lines. The sound of the whole was powerfully unexpected, possibly because “Listening Wind” is a song that Talking Heads generally didn’t play live.

After a brief interlude (four Senegalese drummers), Kidjo came out in a fresh pantsuit and an oversized white jacket—a sly reference to the big white suit that David Byrne wore in the “Stop Making Sense” concert film. She urged a singer off a riser, introducing her as “the singer I wanted to sing like when I came to New York.” This was Nona Hendryx, in full diva regalia: harlequin jacket, patterned stockings, spiked heels. Thirty-seven years after Hendryx sang “Houses in Motion” in Central Park with Talking Heads, she sang it with Kidjo, and the sight and sound of these two women passing the lyrics back and forth gave fresh meaning to the notion of call and response—suggesting that this notion, better than the language of identity or influence, expresses the way musicians respond to the call of songs from other ages and other cultures, making their responses into calls to other musicians going forward.

It was a one-world moment, and yet just as often Kidjo’s band re-rooted Talking Heads songs in American vernacular music. “Burning Down the House” (from “Speaking in Tongues”) featured the Antibalas Horns but had a New Orleans second-line feel. And David Byrne was in the house, it turned out, seated in a first-tier box at stage right. Kidjo, moving through the audience during her song “Afrika,” went upstairs to greet him; a few minutes later, she called him down, explaining that when she played her first U.S. show, in 1991, at S.O.B.’s, on Varick Street, he was there—the first prominent American musician to come see her play.

Now he joined her onstage at Carnegie, dressed in Manhattan mufti: black jeans, black sneakers, and a black fleece vest over a checked shirt—closer to the preppy wear of “Talking Heads: 77” than the big white suit. A week shy of sixty-five, he looked more like Sam Waterston of “Law and Order” than (as Time magazine, in 1986, dubbed him) “Rock’s Renaissance Man.” Possibly, the cameo was unplanned and spontaneous; possibly, it was made to look unplanned and spontaneous, lest Byrne draw the ire of the other Talking Heads by joining Kidjo to play music—their music—that he has refused to play with them for thirty years, except for one night, at the Rock and Roll Hall of Fame, in 2002.

Kidjo and Byrne did “Once in a Lifetime.” Jason Lindner struck the warbling-synth opening, like the startup sound for the eighties; then Byrne dropped his microphone. Starting again, the musicians recast the song’s dark and angular changes in a bright major key, and Kidjo and Byrne traded vocal lines, dancing fitfully with each other. It looked and sounded like they hadn’t rehearsed—like the cameo appearance really was unplanned. Whatever the reason, their call-and-response was clunky and off-balance. She sang freely, exuberantly; he sang with the distinct man-aghast phrasing made famous by the “Once in a Lifetime” video and “Stop Making Sense.” It was a demonstration of the good sense of Byrne’s determination to make new work rather than mine the Talking Heads catalogue. Singing “Once in a Lifetime,” he was drawing on some of the most unforgettable vocal work of our time, and yet (same as it ever was) the vocals were fixed in place, a great artist’s involuntary act of self-sampling.