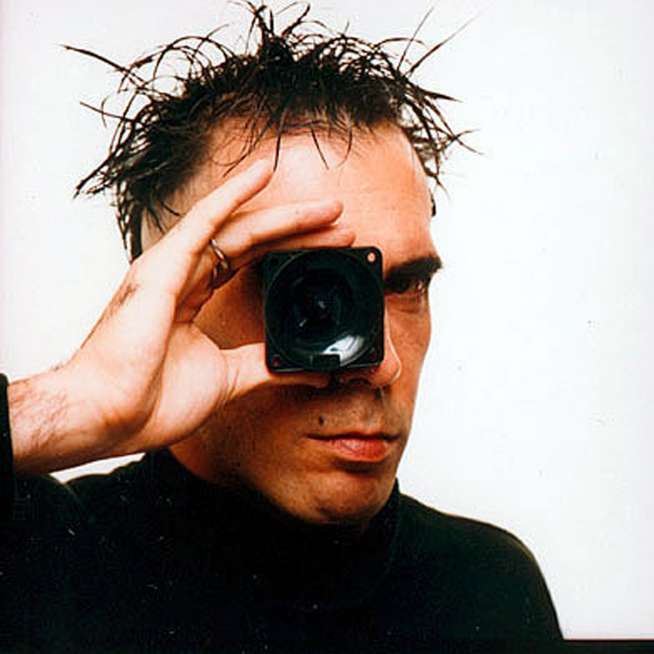

David Byrne on not being afraid to fail

David Byrne on not being afraid to fail

The iconic artist talks about trying new things, being seen as something other than a musician, and creating Neurosociety, a large-scale immersive art piece.

From a conversation with Brandon Stosuy

January 5, 2017

I wanted to talk about your interest in trying new things, which is something you do consistently. Even in the materials discussing your new project, an immersive augmented-reality piece, there’s a part where it talks about being an amateur.

I put it down to being of a generation where the people I looked up to—whether they were science people, music people, pop singers, or whatever—were constantly trying new things. Not quite as outside of music as Neurosociety, but still branching out a lot. Not all the stuff they did was good. I thought, “Well, that’s the way you’re supposed to be. That is what’s cool.”

There are plenty of wonderful artists I like who stick with the same thing through their whole career. But I thought what’s really exciting is when they start doing something new and it surprises you. Or they go from doing paintings to films to videos to performances to whatever else it might be and you go, “Oh, yeah. Okay that’s possible.” It seemed like that’s what you were supposed to do. It was the example that was set for me by the people I looked up to. I thought, “That’s what I need to aspire to.”

When you try something new, there’s a huge amount of risk that something’s going to completely fail. That you’re going to be laughed at. You’re often an amateur when you go into an area you haven’t before. It’s something a lot of musicians do—like going from making music for dance, to music for performance, to music for movies. It’s fairly common. Then to go further and think well, why not just make the movie? It’s a really big leap, but I’m very methodical about it. I’ll test things out with friends, get feedback, see what works. Sometimes test them out more than once. Test it, tweak it, try it again, see what happens.

I miss being able to do that in the pop music world. You kind of have to present something finished. We’ll all do some sort of tryout dates and warm-up dates, but you can’t do a half show. It’s kind of like, word’s out. Other things you can do it a little bit, test it out, see how it works.

When I got to a certain age, I felt comfortable knowing how to do certain things. I feel like I have enough confidence in myself that I’m willing to face up to criticism. If people hate it, they might be right, but it’s not going to be totally devastating.

Are you more interested in doing non-music things vs. doing fully music-based projects?

No. I’m doing a theatrical musical, another one. I did one a few years ago about Imelda Marcos. There’s a new one about Joan of Arc. It’s all written and rehearsed. Well, not totally rehearsed, but I’ve done workshops and gone through that process. It’s due to open Valentine’s Day at The Public. Then maybe go beyond that, we hope.

It’s probably a combination of me being incredibly lucky and incredibly willful that I’ll persevere to do something non-musical. It can be daunting for somebody who’s known in one area to go into another. You face accusations of dilettantism, hubris, you name it. But that’s okay. Sometimes it might be right. The question is, does it work or not.

You’re practicing what you preach with Neurosociety. Can you explain it a bit?

It’s somewhere between immersive theater, haunted house, science exhibit, immersive art-installation, whatever. It’s a little bit of all those things.

In this case, you go through a bunch of rooms and each one is based on a neuroscience experiment, psychology, or something along those lines. Groups of 10 people go through at a time, kind of like a haunted house. You go through in groups, as opposed to individually. There are guides that meet you in each room. They have a little scripted thing they do, some of which is just, “Sit here. Do this. Put this on. Look at this. Tell me what you see.” Then other parts are explanations of what you see or don’t see, or why you did what you did.

For example, there’s one where the room goes completely dark and there are these afterimage effects where your eyes adjust to the darkness. There’s a flash of light and you see your hand or different objects basically grow in size, into this weird proportion.

There’s another thing in that room based on a lab in Sweden. They called it, “Being Barbie.” We don’t use a Barbie doll; we use an American Girl doll. Everybody, all 10 people, are embodied in the body of the doll. They see things through the doll’s point of view. When they look down, they see the doll’s arms and legs. That part works, but what’s really surprising is you start to see everything else from the doll’s scale. Which makes you realize that, oh yeah, my world is scaled according to my body. If my body changes to that of a doll, then everything looks really big. Or really far away, depending.

We also have a fake classroom, like an ’80s classroom. We do an election. You vote on little tablets that you have at your desk. We have this thing called equiluminance, where we can saturate your eyes with a monochrome color. You can blast your eyes with one particular color, in this case a yellow. When only the color cones in certain areas are stimulated and nothing else and if everything else is blocked out, the cones don’t perceive motion or depth. What you see starts to look really flat. It looks like a Warhol silkscreen.

Maybe, before they go in, give people warnings in case anyone freaks out.

We do warn them in this one that there’s a bright flash because epilepsy. But usually epilepsy gets triggered by repeated flashes. This is just one single flash and then a couple minutes go by and you get another one. It’s very unlikely that would happen, but there is a warning there. Then you go into one where it’s like a TV game show. There’s a moderator and a bunch of people on podiums, screens, and stuff. You go through, you vote on things. To begin with, you vote on moral dilemmas.

First you’re asked, are you still you if you lose a limb? Most people say, “Yes.” Are you still you if you have a transplant? Most people say, “Yes.” We have stills from films and different things. We have a film still from a movie of a woman whose body was severed and all that’s left is a head on a lab table. We go, “Are you still you if you have no body? Just a head. It’s your head, your brain, but no possibility of physical action whatsoever.” People start to waver. Then when you go, “Okay are you still you if everything you are is uploaded? If you’re just a lot of data?” Let’s say like that Johnny Depp movie or that episode of Black Mirror that had something like that. People start to waver there and I go, “It’s still all your thoughts but now there’s no body whatsoever.”

Then we show a picture of Herman Munster, Frankenstein and stuff and go, “Okay now here are bits of your body but the brain, somebody else’s brain has been put in.” Almost everybody goes, “No. It’s not me anymore.” He goes, “Okay so we’ve pinpointed the you is in your brain. That’s where you feel like the you is.” Then kind of go, “Okay now if the you is your sense of morals.” A lot of people feel like it’s their moral sense, their political sense, all those kind of things that define what makes them. Then we start to go through these moral dilemmas and we see people kind of changing what the feel, when they would kill somebody, when they would not kill somebody, when they would do that. It’s kind of amusing stuff. We use a Star Trek episode and things like that.

You and I spoke about this project a ways back when you were earlier in the process. Do you think parts of this are going to have a heavier political resonance for people, based on how the election turned out?

Definitely. Some of the stuff in the politics room has to do with moral dilemmas and economics. There’s a group exercise and the idea is that, in an ideal world, you see the possibility of cooperation and trust. Then if you can put that into action, you have a little miniature society that you’ve solved. You’ve at least seen a model of how social interaction can actually work successfully. That is, yes, these days, incredibly relevant. I mean if people walk out with a visceral sense that it can be done, instead of the sense of, “Oh no, we’re permanently divided and yelling at each other for the rest of our lives,” then that’s a really good thing.

The political room is based on an experiment that a guy at Princeton Alex Todorov did. He has a book coming out called Face Value. He’s done lots of studies on how we rate and recognize and evaluate people’s faces. Down to whether we find somebody trustworthy or untrustworthy. He did one where he showed people political candidates from regional elections, very quickly, just faces. You were asked to say if the person was competent or incompetent. He correlated those results with how the candidates actually did in the elections. The people that were voted “competent” generally won the election. It was like a 70% thing.

We took it even further. We asked him, “Can you just predict who you think is going to win, and we’ll tell you if you’re right or not.” It was like 70%. Kind of frightening, just based on faces. You don’t know the party, you don’t know their names, you don’t know anything about them. You just see these goofy head shots.

It’s frightening because we are evaluating people based not on their positions, ideas, actions, or anything else, just on their faces. I’m curious to see if he has any information on if the facial stuff actually does match people’s competence or trustworthiness. I tend to think that it’s just an accident at birth, how you look.

Are you gathering the data from all this?

We are, but very little. People sign-in with their sex and age. Maybe where they’re from, not address but where they’re from. Maybe nationality or race or whatever. There are about four or five different things, not a lot. We’re offering it to the labs that we got the things from. We’ll see. It’s been a discussion because a lot of times in the academic world, they require all this paperwork for data to be legitimate. Each university or whatever has slightly different criteria and it’s a real nightmare. We just said, okay. We can be more rigorous as we go on. Also, the people going through this thing would love to know that how they react and what they do is going to be helpful to science in some way.

Is the ideal scenario for you that people will come out of it having learned something, or you guys will learn something?

For me, the goal is for people to come out having a different sense of themselves. That they feel it in a visceral way, through an experience, as opposed to being told via a documentary or a book or a lecture. They really have a visceral sense of it, which I think is a more profound kind of learning. We’ll see.

One thing I was curious about, too, is do you want people to go into the experience blindly or to have read some background beforehand?

They’ll get stuff when they get tickets. They’ll get stuff online. It gives them a little bit of background, but I want there to be a lot of surprises. Not surprises like oh we’re going to physically subject you to things.

But, yeah, afterwards, they’re naturally going to ask, “How did you guys come up with this?” “Who are you to be doing this?” “What gives you the credentials to do this?” And, “If we like it, how do we find out more?” I think we have to do it in levels, have like a two-page handout like you get in a gallery or something. Then a very, very in-depth thing online where all the papers on this subject, all the research in this area, here you go. You can take it as far as you want.

Do you think you’ve done enough things at this point, and have proven yourself in enough areas, that you’re seen as an artist in general, or do you still have to sometimes shake the perception of being a musician dabbling?

I think I’ve shaken that for the most part, yes. A lot of people are aware that I do different things beyond pop music, or whatever you want to call it. But, yes, there are other people I run into, and all they know are a few Talking Heads hits. There were times when that would’ve annoyed me like, “My life is a little bit more than that. I like those songs, too, but my life is more than something I did quite a number of years ago. It’s a little, tiny sliver of what I did.” But that’s fine, too.

For those contemplating doing a little bit of what I do, that kind of variety of things, I would say you need to be ever-vigilant. For example, a Talking Heads reunion might be incredibly successful for a specific generation, or maybe for many generations. It would make me a lot of money and get a lot of attention. It would also probably be quite a number of steps backwards as far as being perceived as someone who does a lot of different things. For that reason, I feel like I have to sacrifice something, whether it’s money or name recognition or whatever, in order to be able to do a little bit more of what I’d want to do. In other words, you can’t have it all.

David Byrne Recommends Influences on Neurosociety:

Books

The Tell Tale Brain — Vilayanur Ramachandran (He is the originator of the “rubber hand.” Lots of wonderful speculation is in this book.)

Moral Tribes — Joshua Greene (What affects our moral choices–are we only moral and fair within our own tribes?)

The Moral Economy — Samuel Bowles (We make pro-social decisions given the right framing.)

Just Babies: The Origins of Good and Evil — Paul Bloom (Do even babies have a moral sense, a sense of fairness? Is empathy always a good thing?)

Subliminal - Leonard Mlodinow (How much of what we act and do is determined by unconscious forces?)

Sleights of Mind — Stephen Macknik, Susana Martinez-Conde and Sandra Blakeslee (Magicians and magic use and expose the quirks of the mind.)

The Invisible Gorilla — Christopher Chabris and Daniel Simons (We often don’t see what happens right in front of our eyes.)

The Righteous Mind — Jonathan Haidt (How do we make moral and political decisions?)

Thinking, Fast and Slow — Daniel Kahneman (Our intuitive vs. rational mind–how they work together, or don’t.)

Incognito: The Secret Lives of the Brain — David Eagleman (Much of what we are is unknown to ourselves.)

The Brain: The Story of You — David Eagleman (This is a short summary written to accompany a TV series.)

Spaces

The Exploratorium in San Francisco: I got in touch with some guys that worked on the original version of that. This is in some ways a continuation of that idea, but in a more committed and immersive way.

Sleep No More: Certainly the difference there is you kind of wander around at will. That’s completely different. The similarity might be the kind of emphasis on art direction. There’s a fair amount of that.

You Me Bum Bum Train: This is a British theatrical thing they do once a year, for maybe a few weeks, or maybe every couple of years for a few weeks. It happens in some location like an old warehouse or an old abandoned building. It’s a similar kind of thing where you go through a series of rooms, but it’s extreme in that it’s one person at a time. There’s not just one guide in each room, there’s sometimes 100 actors in each room. I haven’t seen them all but there’s one where basically you’re dumped into a room, and you’re the doctor in an operating theater. All the other assistants and everybody is in there and the patient’s there. Everything’s set up and it’s up to you. There’s another one where I think where you’re a musician or performer or something like that and you walk onstage. You walk out, you’re onstage, and there’s all these people in an audience. Each part I think only lasts for a few minutes and then you rush on into the next one and you’re thrown, you’re somebody else. There’s a similarity there because each room is a different kind of thing, but again very different there, too.

People

Justin Lowe and Jonah Freeman: They tend to do rooms that you wander through. Like, “Oh this is an abandoned video store” and “this is an abandoned meth lab” and this is a courtroom.” Again, very art directed. A lot of fun. In those, the difference is, of course, there’s no actors or anything and you can wander around on your own. There’s some similarity there, too. The art is in creating these weird environments as opposed to having things that you hang on the wall. That’s probably the biggest thing that links Neurosociety to a lot of other things. It’s really about an experience as opposed to stuff.

Doug Wheeler: He’s done one where you walk in and it’s just this white space with no corners and no edges and you feel like you’re in a white void. Very strange thing. Really beautiful, but very strange.

Walter Murch: He’s a filmmaker, film editor, and sound designer for films. Just kind of a polymath who’s interested in a lot of stuff. I talked to him about how we perceive sound, because he talks about how you perceive sound in films. He has one idea, I think it’s called the Rule of Three. When you see one person walking in a film, the sound of the footsteps has to match exactly. When it’s two people walking in a scene, the sound of their footsteps have to match up. When it’s three and beyond, it just goes to “many,” and nothing has to match anymore. It doesn’t have to be anything synchronous. He thinks that’s a basic perceptual thing, the possibility that basically we can’t count perceptually beyond three or four.