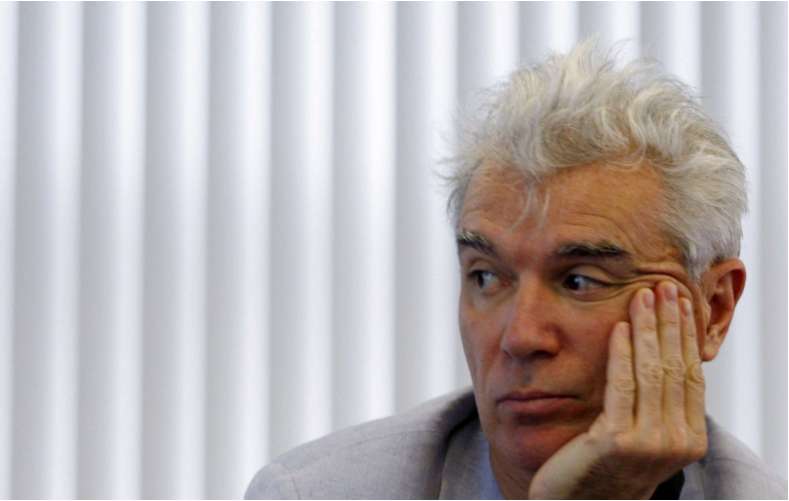

David Byrne Pens Essay On The Unexpected, Terrifying Political Rise Of Donald Trump

By Michelle Geslani

Donald Trump won big at the New Hampshire primary this month, and nearly overtook Ted Cruz in Iowa, much to the fear of Democrats and Republicans alike. In South Carolina, whose primary is set for February 20th, the businessman turned pseudo politician is again leading in the polls and looks to be on his way to a back-to-back victory.

In a lengthy new essay, David Byrne examines Trump’s incredible and unexpected political rise, specifically tackling the question that’s likely on many Americans’ minds: “How are Trump supporters so seemingly unaware of his lies and bullshit, and the ridiculousness of many of his positions and ideas?”

The Talking Heads frontman, who previously broke down the “unknown finances of music streaming,” pointed to a few specific factors that have led to the success of Trump’s presidential campaign: Americans’ distrust in the government; middle-class Americans’ belief that the American dream is no longer attainable; and the popularity of social media, which Byrne says fosters insularity and makes it impossible for Trump proponents to be exposed to criticism and differing opinions.

Below are a few choice excerpts which highlight his points.

On Americans’ belief that Congress answers to corporations, not the people:

“Congress is beholden to the money of special interests and consequently the voice of the people goes unheard. Democrats might blame the Koch brothers and I’m sure that conservatives blame some outside influences, too. The decision to bailout the banks doesn’t sit right with some, and others feel that the government wants to regulate their private lives.

Americans feel disenfranchised—that the government isn’t responsible to the people and instead only responds to the wishes of special interests. In my opinion, the latter is not just a feeling, it’s true.”

On Americans’ loss of hope in the American dream and the opportunity for upward mobility:

“According to a study by Nobel Laureate Angus Deaton and Anne Case, white middle class men may be killing themselves due to an increase in pessimistic outlooks concerning their financial futures. My guess is that the middle class senses the end of the American dream and that white middle class Americans are experiencing a lack of mobility and opportunity in the economic spheres where they were previously the privileged and entitled majority.”

On social media’s “echo chamber effect” of promoting views that one already agrees on:

“The problem with Facebook and Twitter is that those platforms mostly present a point of view that you already agree with, since you only see what your “friends” are sharing. We all do this to some extent—your friends share news with you and presumably many of your friends share your viewpoints. The algorithms built into those social networks are designed to reinforce this natural human tendency and expand upon it—if you like this, you’ll like this.

We would like to think of the web at a place of pluralism—a place where many voices, often at odds with one another, can be heard. A place of diversity. A place to find out what wonderful and unexpected stuff exists that is different than anything and everything you already know. It seems that may have been true with net 1.0, but as market forces increasingly take effect, the diversity of voices, while it still exists, is now so filtered and targeted that you may only hear echoes of what you already believe.”

Toward the end of the essay, Byrne himself struggles to put forth a solution to the hive mind of Twitter and Facebook, but does suggest reading multiple, differing publications and interacting with various diverse communities in a more human way.

“I’m going to suggest that cycling or walking around in different neighborhoods gives one a slightly more face-to-face view of the diversity of humanity, especially here in New York,” he writes. “I love writing songs from different characters’ points of view—characters who are often saying things I would never personally say, but whose shoes I can put myself, sometimes.”

Read full essay here.