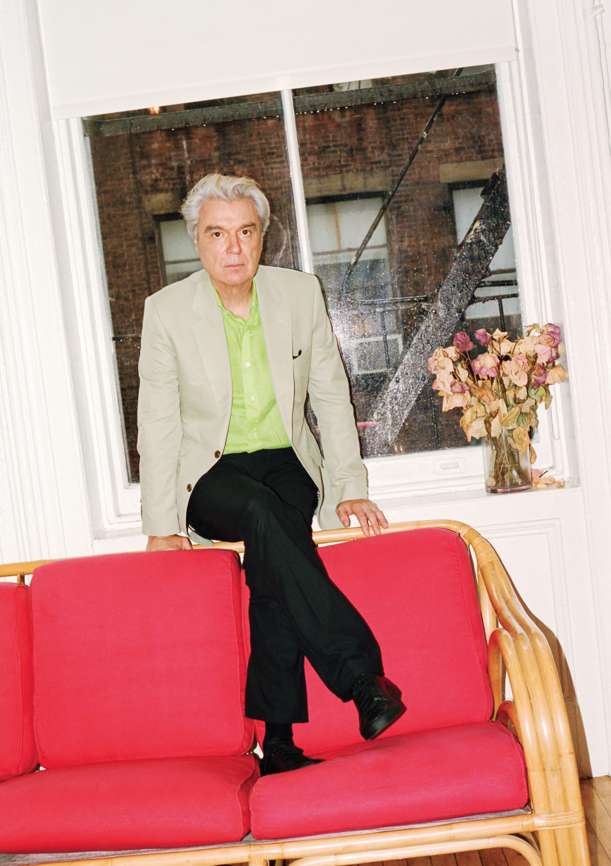

David Byrne’s Beautiful Mind

BRAINPOWER | Artist David Byrne, photographed in his Manhattan studio. His interactive exhibition The Institute Presents: Neurosociety runs through March in Menlo Park, California. PHOTO: CLÉMENT PASCAL FOR WSJ. MAGAZINE

By GABE ULLA

Oct. 18, 2016 2:10 p.m. ET

FOUR DECADES into his career, the 64-year-old musician and artist David Byrne is preparing one of his most unexpected efforts yet: bringing cognitive science to the people. The Institute Presents: Neurosociety, open through March at the Pace Art + Technology gallery in Menlo Park, California, is an exercise in immersive theater in which guests learn about, and even experience, the work of several leading neuroscience labs from around the world.

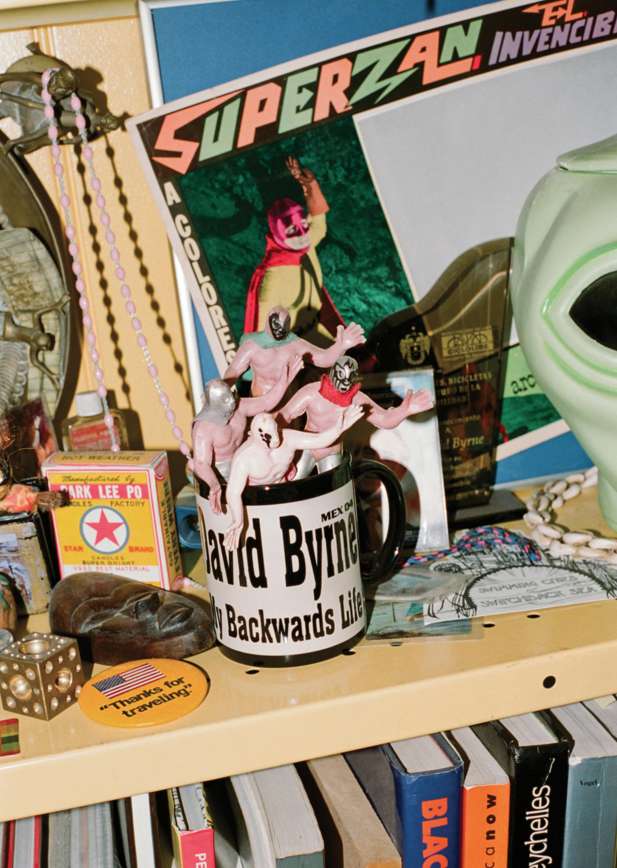

WEIRD SCIENCE | Memorabilia in Byrne’s New York studio PHOTO: CLÉMENT PASCAL FOR WSJ. MAGAZINE

The show is a three-act narrative that seizes on the inherent theatricality of lab experiments, a play about perceptions, decision making and the counterintuitive. The way Byrne and his collaborator Mala Gaonkar, a tech investor based in the U.K., have envisioned it, guides shepherd staggered groups of 10 ticketed guests through several rooms as part of the 80-minute interactive exhibition.

Among the highlights: In Act I, attendees enter a sterile white room, lie down on white reclining chairs and put on virtual-reality goggles so they can see themselves embodied in a doll. (As an internal document describes it, this exercise demonstrates “how our sense of our bodies hijacks our visual sense of the scale of the room and its objects.”) In Act II, participants learn about the work of Princeton psychologist Alexander Todorov, who found that political candidates’ facial appearances are surprising predictors of the outcomes of elections. “Do these facial expressions bring us to Donald and Hillary?” asks Byrne. “It’s a slightly frightening experiment.” And in Act III, subjects see how they fare when it comes to questions of bias and cooperation. More than culling accurate data, Byrne says, “Our hope is that there’s a kind of cumulative sense of how our brains work...and that we give an inkling of a way that the positive qualities we share can be built on. If you are more aware of the negative stuff, you might be able to control it better—where it surfaces and manifests. That is a lot to expect in a pop-up gallery experience, but it’s a start.

A rendering from his Neurosociety show in Menlo Park PHOTO: CLÉMENT PASCAL FOR WSJ. MAGAZINE

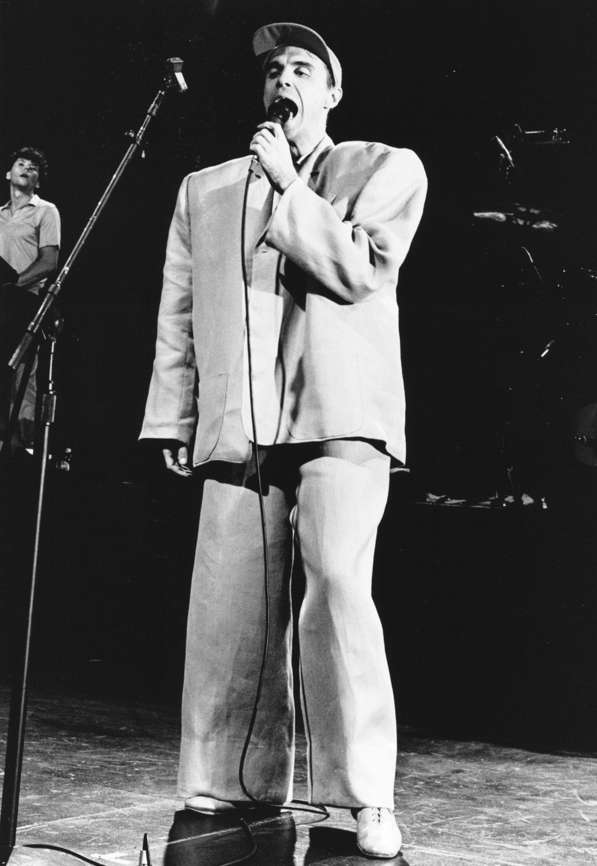

“I’ve always been interested in these kinds of things,” Byrne continues in his unmistakable voice. His bright white hair is still wet from the storm that hit during the commute to his SoHo office. The loft where his small team works is filled with relics from his days fronting the pioneering rock group Talking Heads. There’s perhaps an even greater amount of archived material from his various solo projects in the worlds of music, film, art and theater. “When I graduated from high school, I applied to Carnegie Mellon, an engineering school, and the Rhode Island School of Design, an art school, at the same time,” says Byrne, who was born in Scotland but grew up in the suburbs of Baltimore. “I got into both.” Sensing that the art school route would be “more fun, faster,” Byrne went with RISD. (“I eventually dropped out for the same reason,” he says.)

Following art school, Byrne led Talking Heads for more than 15 years; composed an Oscar-winning score for Bernardo Bertolucci’s The Last Emperor; sang with Celia Cruz on his first solo album, 1989’s Rei Momo; published several books, including Bicycle Diaries, inspired by his cycling habit; and collaborated with Fatboy Slim on a musical, Here Lies Love, about former Filipino first lady Imelda Marcos. Somewhere along that path he also started reading science papers. There’s a big box of them in his office, and he can call out specific researchers as if he’s talking about his favorite musicians.

Byrne first explored the idea of doing something with science when Pace, which represents him as an artist, was opening a space in London. “I would like to experience [these experiments], and I’m guessing a lot of other people would, too, once they find out about them,” Byrne says he told the gallery. At the time, it didn’t work out. But the possibility surfaced again a few years ago, when Byrne’s friend and collaborator, the fellow musician and polymath Brian Eno, introduced him to Gaonkar. “It is certainly not the kind of obviously sensible idea on which one would normally embark,” Gaonkar, 46, says of Neurosociety. “Yet from the first conversation with David, who seems to have an enviable facility for hopping borders normally walled off to the experts, the idea acquired a logic of its own…. It seems we all wish to understand what frames our brains.”

A sketch of Tight Spot, an almost 50-foot inflatable globe under Manhattan’s High Line, designed by Byrne for Pace in 2011. PHOTO: DAVID BYRNE, TIGHT SPOT (ARTIST RENDERING), 2011, EPSON INKJET PRINT ON ACID-FREE EPSON VELVET FINE ART PAPER WITH ACRYLIC AND GRAPHITE, 14" X 19" (35.6CM X 48.3CM), © DAVID BYRNE, COURTESY OF PACE GALLERY

To pull off the installation, Byrne and Gaonkar realized they would have to develop adaptations of the experiments. They traveled to different labs, where researchers demonstrated their work and fielded questions. “I was really impressed by him,” says Todorov of his first meeting with Byrne, a conversation that ran for an hour. “He had done his background research.”

“He has a grasp of subjects that may seem above or below [audiences], and he helps people understand them,” says LeeAnn Rossi, Byrne’s creative producer. A recent project she helped oversee for him was Contemporary Color, a performance that paired high school color-guard teams with the likes of musician Dev Hynes and This American Life host Ira Glass. Appropriately enough, one of the rooms in Neurosociety resembles a typical high school classroom, while another looks like the set of a game show. “You have to give a little wow factor,” Byrne says.

THE MUSIC MAN | Byrne in 1983, performing with Talking Heads. PHOTO: CHRIS WALTER/WIREIMAGE/GETTY IMAGES

Last December, Byrne and Gaonkar held a workshop on Governors Island featuring about a dozen demonstrations that they then edited down for Neurosociety. This past summer, they set up a makeshift lab in the Brooklyn Navy Yard to try out experiments for friends and scientists. “It was like calling Ikea, telling them we followed the directions but it still wasn’t working,” Byrne says of reaching out to scientists while his team worked out the technological challenges. The process revealed to him the improvisational quality of scientific research: “We found out that like music and the arts, science involves a lot of futzing around. It was a shock but also a relief, since that’s sort of the way I work.”

If Byrne and Gaonkar have their way, Neurosociety will grow into a larger project integrating work from even more labs (as of now, they’ve consulted with 35 institutions). The first incarnation of their initiative will still be on view this coming Valentine’s Day, when Byrne debuts his musical, Joan of Arc: Into the Fire, at New York’s Public Theater. And there’s a mood board dominating the wall behind his desk with ideas for another, unannounced project.

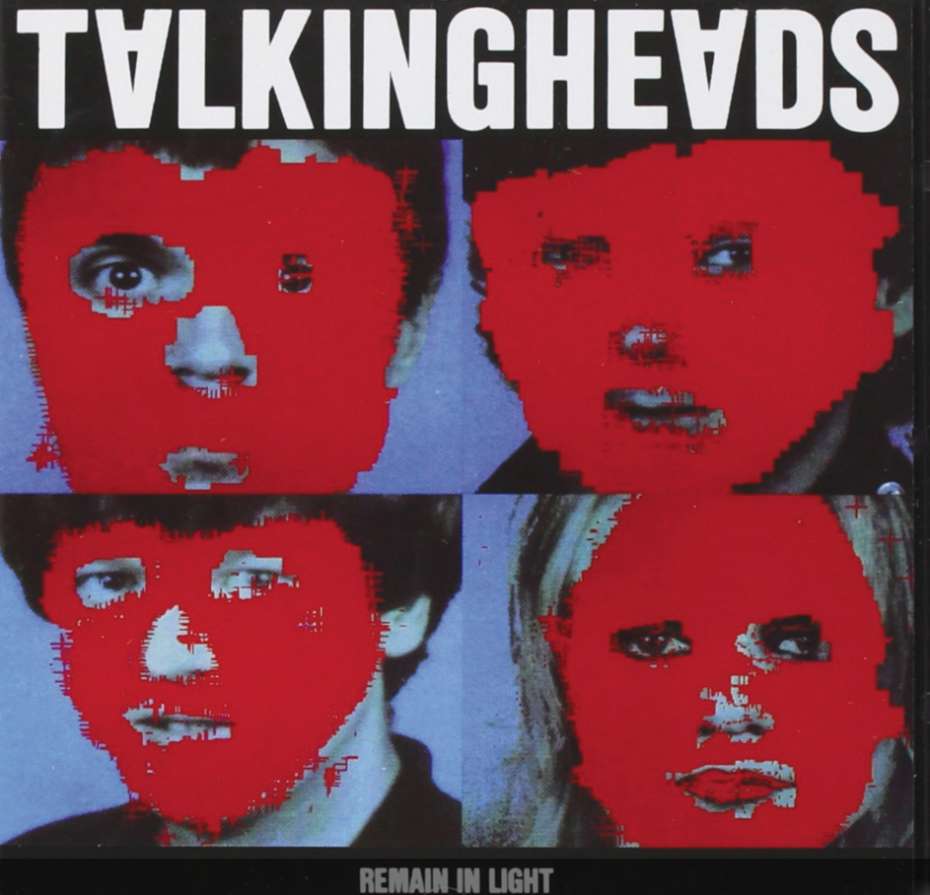

The band’s album Remain in Light, released in 1980.

“I think he views touring and making music as work, and everything else as relaxing time,” says Rossi. “We’re always doing eight to 12 things at once, and they’re all different, yet they end up overlapping and informing one another.”

“There’s a lot,” says Byrne of his output. “But it’s all incremental.