David Byrne on the Music That Made Him

Via Pitchfork

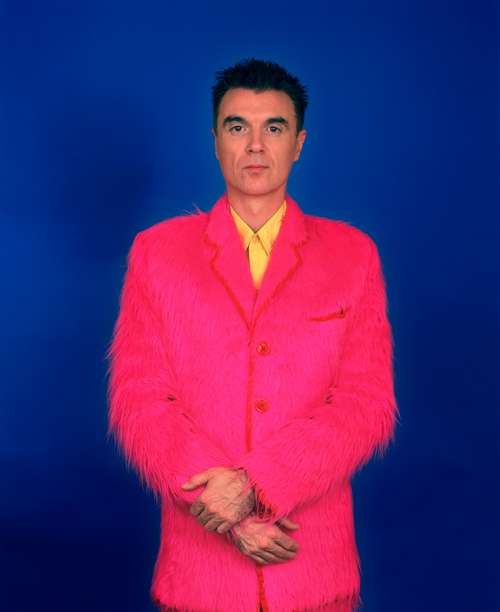

Photo by Jody Rogac

By Stacey Anderson

Ever the overachiever, David Byrne has spent the last four months tackling his most ambitious project yet: cheerfulness. But not the kind we’ve seen from the Talking Heads legend before—the ecstatic type that once prompted him to flutter and convulse while yelping about infinity, or the esoteric intellectualism that resulted in books about bicycling as a window to urban psychology and the physics of music. No, the hill Byrne beckons us up now is the kind of retiring optimism that feels not just foreign to many Americans today, but willfully wrong.

Byrne has made no secret of his displeasure with our current president and the economic gulfs in his longtime home of New York—a few reasons why, in his words, “it often seems as if the world is going straight to hell.” But he has lately been offsetting such hopelessness with Reasons to Be Cheerful, a new multimedia project that basks in positivity through shared blog posts and TED-style roving lectures delivered by Byrne (occasionally in a dapper millennial pink blazer). With insights on everything from progress in prison reform to witty signs at the Women’s March, the 65-year-old is taking time to revel in the details that make the slog of modern life worth enduring.

Looking back at Byrne’s long career, it feels as though that same complicated joy has been his through line. Born in Scotland and raised in outer Baltimore, the former visual art student boosted Talking Heads to mainstream fame and critical adoration with his mix of wiry intelligence and dry detachment over effusively warm pop. Since the group’s split in 1991, in his reams of solo and collaborative projects, Byrne has dared to stay polarizing while maintaining his gift for bright pop hooks. American Utopia, his latest solo record, offers anxious, often surreal ruminations on gun violence, social consciousness, and personal relativism over deceptively brassy soca beats, peppy guitar, and chipper synths.

In his day-to-day life, his ears are still piqued, too. On a recent dim winter afternoon in downtown Manhattan, not far from where the Talking Heads once scorched the CBGB stage, he tells me about his morning, which involved soaking in a hot bath while listening to Janelle Monáe’s latest and watching a Detroit high school choir take on his new track, “Everybody’s Coming to My House,” for a gorgeous new music video. “Really nice things to wake up to,” he says.

Here are some of the other songs and albums that have soundtracked Byrne’s life, as told by the man himself.

Woody Guthrie: Songs to Grow on for Mother and Child

In 1950s Baltimore, my parents were pretty open. They read The New York Times and listened to Woody Guthrie records, so you can imagine what kind of a household that was. They were immigrants from Scotland, and their taste included a lot of American folk music like, Woody and Pete Seeger, both of whom made children’s albums, so that’s what I would hear. Later, I heard their other songs, which obviously had a political slant and a story to tell and a point of view. That was something to realize at a young age: that a song could do that.

Jean Redpath: Jean Redpath’s Scottish Ballad Book

In 1962, I was still listening to my parents’ records and vaguely aware that there were other things out there. Jean Redpath, a Scottish folk singer, sang in a kind of clear, quavery voice. They were traditional Scottish songs, but very simple arrangements, like folk versions.

The Scottish influence was a big part of my parents’ record collection. They didn’t have Scottish bagpipes or anything; they were more interested in Scottish roots music: Woody Guthrie, Ewan MacColl, and different people from that era, who were writing folk songs that were vaguely political but also beautiful. I realized that this sounds very palatable and pretty on the surface, but there's something darker going on underneath.

The Byrds: “Mr. Tambourine Man”

The Bob Dylan song “Mr. Tambourine Man,” was like a psychedelic version of a Woody Guthrie song. But then the Byrds turned it into something unlike anything my young ears had heard before. It sounded like jangly pots and pans, bells. If you’re someone who grew up in the suburbs of Baltimore, the song is like a little telegraph from someplace else. Hearing that, I realized: I have to get out of here, because there are people in other places. There’s a whole world out there that I don’t know anything about.

I had an idea that I would play great literate rock songs in coffee houses around Baltimore. I did that for a little while, which was kind of ambitious for a high school kid. I’d do songs by the Kinks or the Who, or songs with really insightful lyrics that the folkies had never heard before. My parents went to my shows once in awhile, but not a lot.

A few years later, when I was still in the art school orbit, I visited New York City. A friend and I had a group where I played ukulele and violin, and he played accordion, often in the street. We played standards and were kind of eccentric-looking. I would dress in old suits and had a long beard, and kids would come up to me and say, “Mister, are you one of those men who don’t drive cars?” I was not.

We’d heard about the Warhol scene at Max’s Kansas City, and so my friend and I went in there—with the full beard and everything—curious to see where the cool people were. We were so out of place, and I remember David Bowie came in dressed in his full glam outfit, with the orange hair, the space suit, everything. And I just thought, We don’t fit in here. We better go.

The Velvet Underground: “Candy Says”

By 1972, I’ve finished up in art schools, hitchhiked around the country, and I moved to Providence, Rhode Island. In the mid-’70s, I was in a band with Chris Frantz from Talking Heads, and I wrote a couple songs that stuck during that period, including “Psycho Killer.” We also did a lot of cover songs—Al Green, Velvet Underground, the Sonics, the Troggs.

The Velvet Underground were a big revelation. I realized, Oh, look at the subject of their songs: There’s a tune and a melody, but the sound is either completely abrasive or really pretty. They swing from one extreme to the other. “White Light/White Heat” is just this noise, and then “Candy Says” is incredibly pretty but really kind of dark. As a young person, you go, What is this about?

Now I’m in New York, in a band with Chris Frantz and his girlfriend, Tina [Weymouth], and we didn’t have a super-duper plan. I had ambitions to be a fine artist and show in galleries, but I was also writing songs. This club, CBGB, had opened around the corner, and there were bands like Television playing, and Patti Smith was doing poetry readings. We thought, If we learn some songs, we can play there.

I had a day job as what was called a “stat man” for a company that designed Revlon counter displays. So I worked in a little dark room in the middle of this office—which meant I had a little radio in there, and I could listen to music. And nobody else would bother me.

Bowie was on the radio a little bit, and he was a huge influence for a lot of people. I was aware of all the Ziggy Stardust stuff, and then him moving onto the Berlin stuff. Somewhere around this time, in the late ’70s, after we made our first record, we met Brian Eno, who had worked with him on Low, and that was very cool for us.

In 1980, I went with Toni Basil to see Bowie in The Elephant Man. He was reading the collected speeches of Fidel Castro at the time, and he gave me the book and said, “You might enjoy this.” I dutifully read it. Castro could really ramble on. Really ramble on.

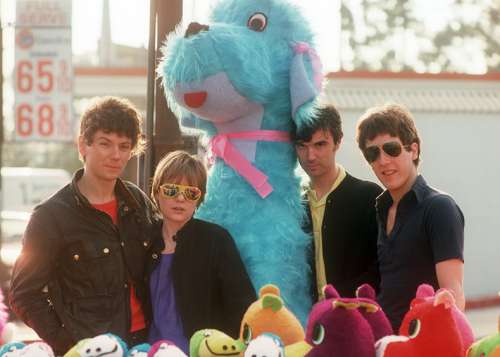

Byrne at age 25 with Talking Heads—Jerry Harrison, Tina Weymouth, and Chris Frantz—in 1977.

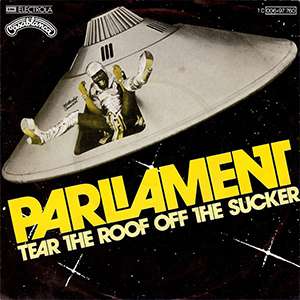

Parliament: “Tear the Roof Off the Sucker”

In Talking Heads, the record collection was filled with Hamilton Bohannon, James Brown, Roxy Music, Funkadelic, and P-Funk, that whole world. George Clinton and his whole crazy P-Funk philosophy was great; they were doing these kind of spectacles.

As we kept making records, they evolved into more rhythmic affairs, kind of weird, white-person funk. We decided that in order to represent this music live onstage, we needed to recruit some real funkers into the band. The size of the band pretty much doubled. It was a big, nervy thing to do, and it was a mess at first. But man, was it fun.

In this period, I decided to formalize the tour into a show that became Stop Making Sense. And that was about as far as we could go with that idea. It liberated me musically, but also as a person. The music was a lot more ecstatic, almost trance-y; you could get lost in it, way more than you could when it’s just a four piece.

Caetano Veloso & a Outro Banda da Terra: Muito (Dentro da Estrela Azulada)

There was a record store in the Times Square subway station, and another one on 42nd Street, both of which had big “international sections,” as they called it. It included everything from the rest of the world, all on vinyl, but with no information. You’d look at the cover and go, What’s this like? It was a total crapshoot. But occasionally, I’d hear something that would blow my mind, like a Fela Kuti record; the first one I picked up was called Expensive Shit, and obviously I picked that up because of the title. The covers were the best—like Cambodian pop records with a bunch of people in traditional garb, all holding electric guitars—and you’d look at them for clues. You’d think, What in the world could that be? You’d buy it, and it would be pretty cool.

In 1986, I did a fiction film called True Stories. I guess you would call it a musical comedy. We were doing the mixing in San Francisco, so I’d go down to the big Tower Records on North Beach and go to the international section. One day, I came back with a whole bunch of Brazilian records, because I had maybe heard of a couple of the artists, but didn’t really know what their records were like. One was a Caetano Veloso record called Muito, and then there was a Milton Nascimento record, and probably a Gilberto Gil record, and those blew my mind. They had elements that were psychedelic and that had a Brazilian feel. They were really beautiful, but then I dug a little bit more and found out they were also really political. These guys had been exiled, thrown in jail.

I was connecting with it, and I realized that my generation didn’t know any of this music. So I asked our record label, “Can we license this music, and can I make a compilation of my favorite cuts?” That one record led to another one: There was a Brazilian series, then a Cuban series, because Cuban music had not been available in the United States for decades. And I started my own label, Luaka Bop.

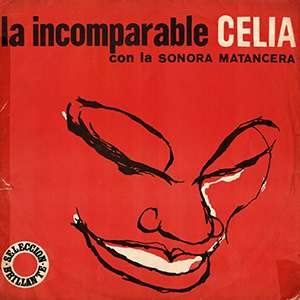

Celia Cruz Con La Sonora Matancera: La Incomparable Celia

I was listening to a lot of Cuban music and salsa, a lot of Latin music. I worked with Selena on the last thing she recorded. And there was a whole series of Celia Cruz records I loved. I did a duet with her for a Jonathan Demme movie, Something Wild. Her early Cuban records were done with a band called Sonora Matancera; those are really great.

Instead of going to rock clubs, I would go to Salsa Meets Jazz downtown and the Corso Ballroom uptown to hear salsa bands. There was lots of dancing. I liked the idea that you were dancing to live music, not just DJs, and grew to really love the music. It opened me up to a lot of sentimentality and feelings that maybe didn’t come naturally to me.

I decided I wanted to do a salsa record, which I did in the early ’90s. And I did another one a few years after that. It was a little less strictly salsa, but it was still in that vein, and I had a wonderful time with a huge band, [Rei Momo]. We toured everywhere, and a lot of folks in the United States did not like it at all. Oddly, people in Latin America really liked it, but not because it was their music. For a lot of their rockers in Argentina or Mexico, it was like, “He's playing our parents’ music.”

Björk’s Debut and Post were mind-blowing records at the time—that somebody could use electronic beats and then do super innovative stuff with it. Then she continued doing things that explored lots of different other areas, with the Greenland Choir and with sounds made with the mouth. Once in awhile you see this amazing total artist, where you go, This person thinks about the stage, the shows, the costumes, the record covers, and the music, and it’s all part of a total thing.

A 47-year-old Byrne in 1998.

The Flatlanders: One Road More

There might have been personal things in my life right here, because I wanted to strip things down. Another inspiration was a lot of country singer-songwriters. I’m friends with a guy named Terry Allen, who’s a great, very eccentric songwriter. Both of us have worked with Lucinda Williams, who everybody knows is an incredible songwriter. There’s an early group called the Flatlanders, and their first records or demos were just amazing. I was really immersed in these people who were writing very simply, as far as their musical arrangements, and very heartfelt. I was getting a lot of inspiration from them.

I was immersed in jazz for a while. I had certainly been aware of it for years, particularly the electric Miles Davis stuff, but this was a period where I went back into it and listened to a lot of Thelonious Monk records. I really love those; they’re so spiky-sounding. There was a whole bunch of Miles Davis electric records that were just never released in this country. I think Columbia or CBS or whoever it was just decided, “We don't like this stuff. We’re not gonna release it.” So you’d have to get the Japanese version CD. But it’s just amazing stuff.

Dirty Projectors: Swing Lo Magellan

Some of Dirty Projectors’ records were a little bit impenetrable, because Dave Longstreth obviously had some really crazy concepts. A whole record was about Don Henley. Then they moved into stuff that was still really innovative, but a lot easier to understand and enjoy, even if it had very eccentric meters and rhythms and melodies.

I collaborated with Dirty Projectors on a couple songs for a charity record, and at our performance at Radio City Music Hall, I met Annie Clark [of St. Vincent], who I was a big fan of already. Then we crossed paths again at a show Björk did with Dirty Projectors at Housing Works [Bookstore in New York]. The Housing Works crew saw Annie and I enjoying the show, and they approached us about doing something together. The idea was that we would do it at the bookstore, which never happened. We certainly donated money to them, but by the time we did an album and tour together, it became a bigger thing than something we could do at Housing Works.

William Onyeabor: Who Is William Onyeabor?

I parted ways with Luaka Bop maybe 10 years ago—it was taking too much of my time and my money and my house. But the label still goes on. And they’ve done wonderful things, including this album by the African electronic musician William Onyeabor a few years ago. And then they put on shows of people like myself and others performing his songs. They continue to do great things.