HOW CHANGE HAPPENS

| June 7, 2016

Never doubt that a small group of thoughtful, committed citizens can change the world; indeed, it's the only thing that ever has. - Margaret Mead

My new musical about Joan of Arc, which we’re currently workshopping at The Public Theater, has me considering lots of so-called dissidents, revolutionaries and heroes (depending on who's writing the histories). What drives them? When are they successful? When are their actions justified?

In a piece for The Guardian last week, I looked at two such determined individuals, Daniel Berrigan, the “peace priest”, and Ammon Bundy, an equally impassioned fighter for his cause — though one who, unlike Father Berrigan, has taken up arms in his protest.

The past and present are full of such lone folks or small groups who act on their consciences.

Outliers with a better idea

We all know examples in which the individual or small group has come up with a better idea than the crowd, a fairer sense of justice, a prescient way of looking at things the rest have missed or willfully ignored. Where do they get these ideas? Joan claimed God, or “The King of Heaven” as she called him, commanded her to act. Others claim it is something internal — a conscience, a moral sense that transcends the rule of the state.

I would argue that we do indeed have an innate moral sense of fairness (though usually just towards our tribe) and that we also arrive at conclusions in these matters by reasoning.

Often at the moment of their insistence, these individuals are viewed as apostates. But that sometimes changes. U.S. Attorney General Eric Holder has just admitted that Edward Snowden, previously viewed as a traitor, did indeed provide a much needed service, though he still offered the caveat that “we’d still need to lock him up.”

Democratic states (and dictatorships, too) maintain that for a nation to function smoothly we must abide by predetermined rules and laws. In this view, we as individuals should adapt and conform, subsuming the self for the greater good. Everyone can’t let their conscience (or their personal God) dictate their own laws.

But are there exceptions? Are there times when it’s O.K. to break the law? Necessary even?

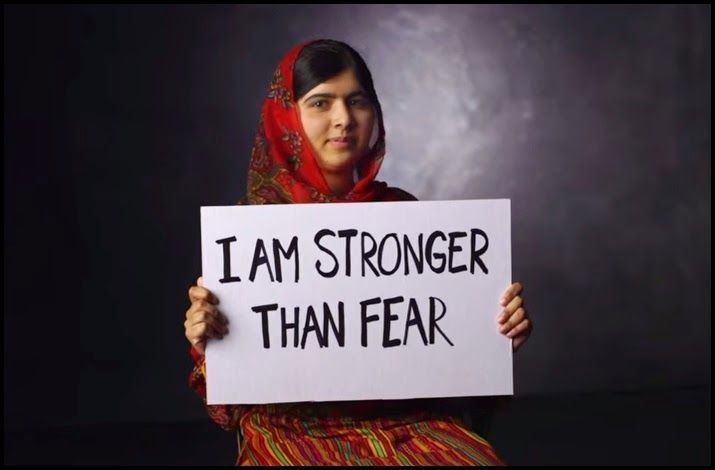

There is Malala Yousafzai, the brave Pakistani girl who believes women should have a right to education. She was shot by the Taliban, who are in effect a kind of pseudo state in the area where she lived. Much of the world seems to be on her side, since she did win the Nobel Peace Prize and now speaks openly from the United Nations to the White House. Yet that was not what inspired her. She knowingly placed herself in danger for the sake of her beliefs.

There are many such instances where, from an outside point of view, or in retrospect, an individual is right and the state is wrong — and where change has gradually and peacefully happened as a result of that individual, or individuals, speaking out. I would argue that these people are often articulating the unspoken and nascent thoughts and feelings of the many. Consider Karen Silkwood, Nelson Mandela Mahatma Gandhi, Erin Brockovich, Julian Assange, Edward Snowden, Chelsea Manning, Aaron Schwartz, Aung San Suu Kyi, Herve Falciani (who leaked the HSBC bank data) The Zapatistas, the hunger strikers in Northern Ireland, and Mohamed Bouazizi, the Tunisian fruit vendor who set off the Arab Spring by setting himself on fire after he refused to pay a bribe to the police.

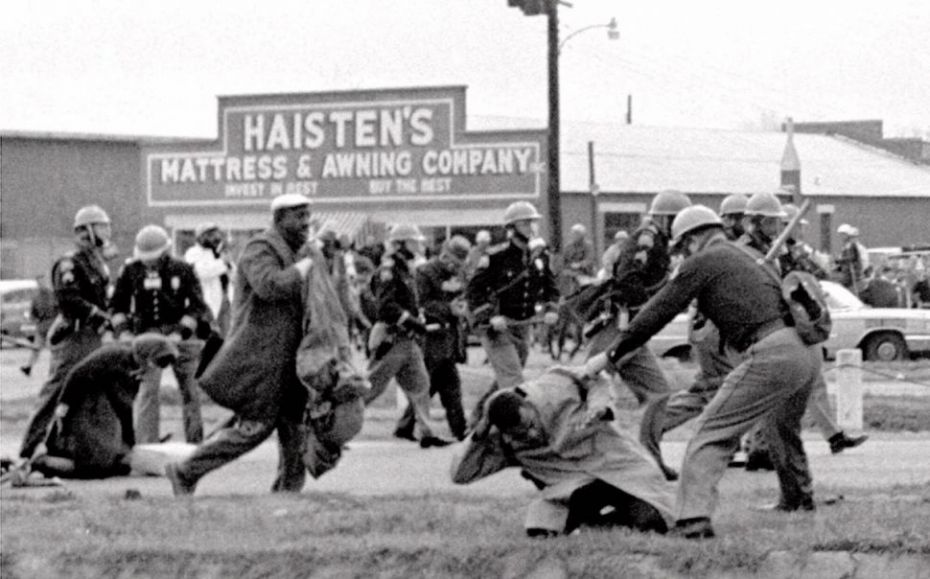

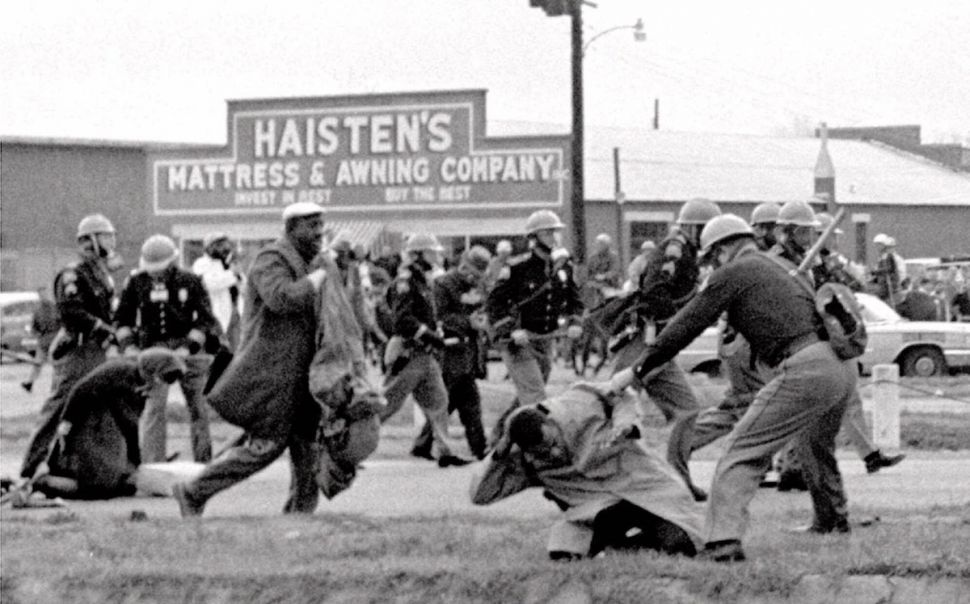

Lot’s of these people ended up persecuted or in jail, and some fared far worse. But all of them acted peacefully and one could argue triggered awareness and change that was nascent, just waiting to be articulated. They acted alone or with a small group but could not have achieved the change they hoped for without the rest of us sensing they were right and eventually agreeing with them. We celebrate MLK Day (thank you, Stevie Wonder) to honor a man who repeatedly broke the law. To some, he was nothing more than a criminal, or worse. Thank God our minds can change.

Shouldn’t we also then support others who act on their beliefs in a nonviolent way who won’t be getting Nobel Prizes anytime soon? Like Kim Davis, the Kentucky county clerk who refused to marry gay couples. Isn’t she acting on her conscience and religious beliefs as well, even though the law is no longer on her side. And the teachers who refuse to teach evolution….they’re acting on their beliefs, too, even if sometimes in violation of the law.

I would argue that all of these individuals should be treated equally. I may disagree with the folks above — but if their actions are nonviolent, I can’t simply exclude them because I think their ideas are offensive. For change to happen the larger population needs to be aware of the dissidents’ protest and actions. To some extent,the success of this path to change depends on a free press — we can only come to a consensus or realization around an issue if we know the issue and the actions of the dissident bringing it to our attention.

When whistleblowers are silenced, when their revelations never see the light of day, change comes to a halt, as it does when the press is muzzled (as Donald Trump has said he would do, and maybe Peter Thiel... and Apple refuses to allow images of drone strikes) or afraid to publish some stories (many, many media outlets passed on the Panama Papers). These brave individuals may act on their consciences no matter what. But to be effective, their message must be heard.

Is it ever O.K. to kill?

Not all who aim to create a more just society stick to nonviolent means. Joan of Arc instigated the process by which France was liberated from the English occupation through violence. For this, Joan is viewed as a heroine, and even a saint. Her determination to liberate France and bring her people self-determination is cheered to this day. The fact that she’s an innocent teenage girl from a small village, a nobody, makes her even more attractive — she is not some conniving child of royalty from Game of Thrones. Like the folks Margaret Mead refers to (never doubt a small group…), Joan is an example of one person, initially with a small group of followers, who made a difference.

Yet if we look at her from another point of view she’s a religious insurgent inciting a holy war. Looking at Joan this way is guaranteed to trigger a contemporary emotional reaction — one I aim to stay clear of as I write the new musical, though I still hope the audience might make that same inference without being told. They can both emotionally endorse Joan and at the same time rationally say to themselves, “Wait, hold on a minute… what am I signing on to here?”

Are there any instances where violence by a small group might be justified, then? The American Revolution? The Mexican revolution of Zapata? What about those in Cuba or Iran? We might feel those causes were worthy — and that the use of violent means was therefore justified. Still, in the American Colonies, only the white male landowners were liberated, and even then the main complaint (as now, it seems) was taxed. Civil war and isolation resulted from the rest.

The prolific writer William T. Vollmann attempts to answer these same questions of violence in a series of seven books, “The Rising Up and The Rising Down.” Over the course of more than 3,000 pages, Vollmann looks at history to ask himself what his own moral values tell him about bearing arms.

Picking up weapons to defend against oppressors and invaders in defense of innocents, especially those whose lives are threatened, seems mostly to be considered unfortunate but justifiable. You must know when to stop, though, lest we trigger a cycle of revenge. This action, if kept within bounds, is not violence for ideals, for a cause, or for beliefs (all of which Vollmann considers suspect), but in defense of lives in imminent danger. I’d tend to agree — to stop slaughter, violence may be justified.

Those justifications are forms of defense, and here we have been mostly talking about something else. Whether Joan of Arc, Martin Luther, Mahatma Gandhi, or Martin Luther King, these are people acting in defiance of injustice. They are not defending their lives or those of their loved ones or their community (though they might argue what is injustice but another form of violence?).

Again, the effectiveness of these acts — acts of disorder and civil disobedience — really only work when the Rosa-Parks-like refusal, and the overreaction to it, become public. I’d propose that resorting to violence in defence, as Vollmann writes, might be justified, but in order to advance and initiate change, it is not only unjustified but often ineffective, too.

That may mean Joan was out of line. Even George Bernard Shaw, who wrote a (not very good IMO) play shortly after she was canonized, said in his long introduction that the church and state had to do what they had to do. As happened with Gandhi and MLK, the eyes of the world (well, Europe) were on Joan’s trial and her treatment. They tricked her and wore her down, but they went by the book. Or let it at least appear that they did. But when she was burned alive, a line was crossed, and the insurgency she had started gained steam. The general population decided she was right. Maybe they were just responding to the violence that had been visited upon her.

When change becomes inevitable

The Dalai Lama says, “For change to happen in any community, the initiative must come from the individual.” I would argue that for change to happen, to be realized and take root, the community must already be ready for that change. The nation, or the majority, is ready for a change of heart, the culture is in flux, the path has been cleared. Anti-slavery initiatives never would have found traction in classical Rome. Even in North America and the U.K., where sentiment was changing, it took almost a century for Abolitionism to finally take hold. When folks are ready to change, the small group or individual’s actions help those nascent feelings to gel.

I think we can agree that this a good way for change to happen, for injustices to be brought to light, as long as the actions are nonviolent and the dissidents are prepared to deal with the consequences of their actions. Joan was burned. Martin Luther King was shot. Father Berrigan and Mandela spent many nights in jail, and it looks like Ammon Bundy and a half-dozen of his compatriots will, too.

So, this is how it works, these people offer us a way to change the narrative. If we accept that new way of looking at things, and often it is a conclusion we were coming close to ourselves, then we arrive at a place where we agree. From the recent book Sapiens by Yuval Harari:

“The ability to create an imagined reality out of words enabled large numbers of strangers to cooperate effectively ….Since large-scale human cooperation is based on myths, the way people cooperate can be altered by changing the myths – by telling different stories. Under the right circumstances myths can change rapidly. In 1789 the French population switched almost overnight from believing in the myth of the divine right of kings to believing in the myth of the sovereignty of the people.“

As unreliable and easily manipulated as the democratic mob is, we rely on the eventual agreement and consensus of that wider population to determine when a policy, behavior or law is morally wrong. When that happens they often collectively act to remedy it. We’re malleable, we as a species can change the myths and narratives that we live by.