RUSSIAN SURREALISM

| October 14, 2014

I joined Brian Eno and some others for an early morning (for us) look at the Malevich show at the Tate Modern. Achim Borchardt-Hume, who curated the show, walked us around.

As we walked up the steps to the show, Mala Gaonkar, a Tate trustee who helped set this tour up, told me a story about contemporary Russia. She said that a web group is currently in charge of creating and spreading chaotic misinformation. Good examples of what they do are the various stories circulated in the Russian media regarding the downed Malaysian airliner. One story that was “placed” in the news was that the plane was filled with corpses. (I presume this story was meant to imply that the plane was crashed on purpose—an effort by the West to discredit Russia.) The organization spreading these fictions isn’t content to come up with just one such story—the modus is to spread lots of different ones, so that a chaotic situation can be established.

It’s not propaganda or self serving “news” in the usual sense—it doesn’t support a position in an obvious way—but rather, establishes the existence of a crazy universe. A place where you really don’t know what’s going to happen from one minute to the next.

Gaonkar knows someone in this organization and asked him why he puts out such craziness. He said one doesn’t really have a choice when there is a gun to your head.

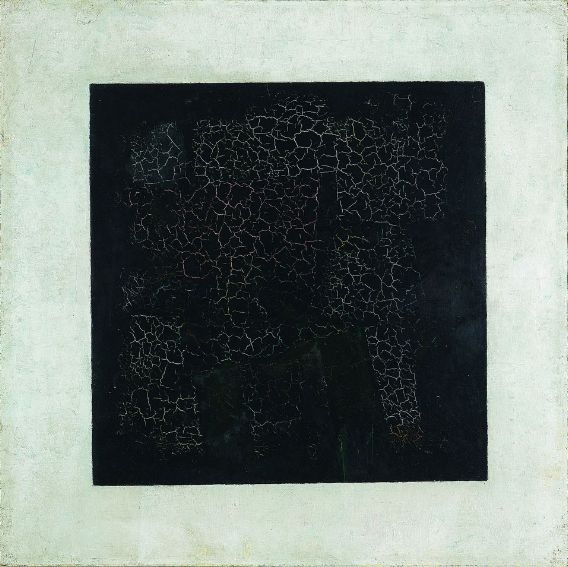

The Malevich show is wonderful. Achim boldly installed two of Malevich’s most iconic minimal works—a painting of a black square and a black and white quadrant—in a room where there is also a video of a CalArts performance of the avant-garde opera Victory Over The Sun.

In a more conventional installation, those paintings—the precursors to a lot of abstract art all over the world—would have been given the holy Rothko treatment: presented alone in a chapel-like space as if they were icons. But it was his involvement in the opera that led him to make the leap to minimal, non-objective painting—he wouldn’t have done it otherwise—so it made perfect sense to present the two together.

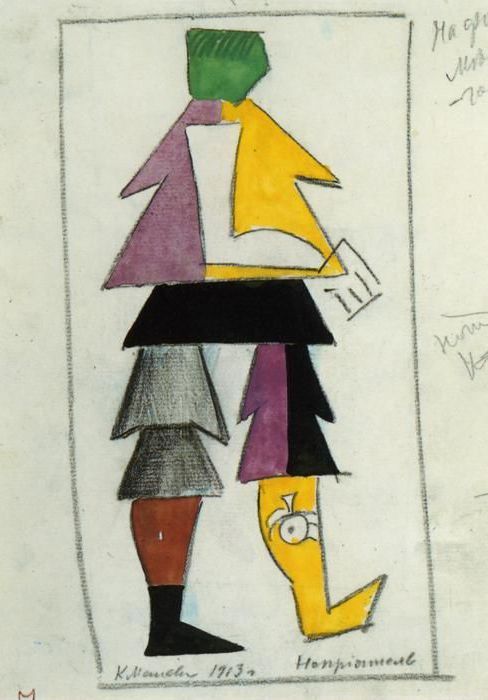

Malevich famously did the costumes for the opera—three-dimensional Cubist constructions that also obscure the actors’ faces. It’s quite Dada and surreal, in a very Russian way. To me, there are elements of traditional Russian peasant wear here (in the costumes, not the square), although exaggerated to an extreme degree. This fits with what Achim said that Malevich and his pals wanted: to find a way to be contemporary (they were aware of what was happening in Europe) but still maintain their Russianness. I’d argue that the square and the circle, etc., were functioning a bit like Russian icons—paintings in which the actual object’s beauty, execution or elegance is of almost no importance. An icon can be a tiny painting that is not so special, but once nominated—once folks believe it has the idea and the aura in it—then it is regarded as a holy relic. People kiss them and parade them in the streets: it’s their symbolic value that matters, not their visual or artistic quality. (Sounds like much of conceptual art to me.) They can, it is believed, change lives. I think that for a minute the Russians believed their vanguardist art could do that too.

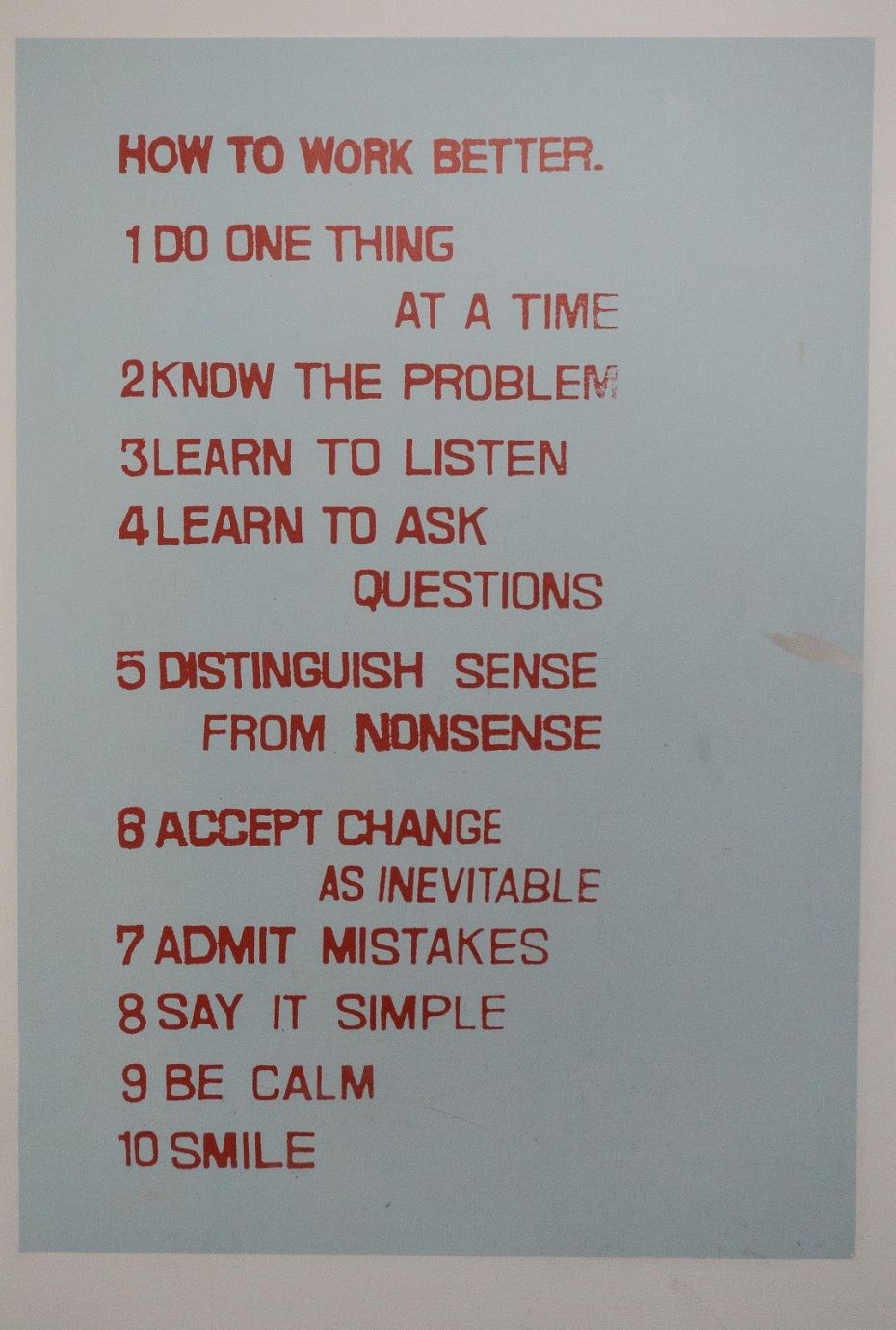

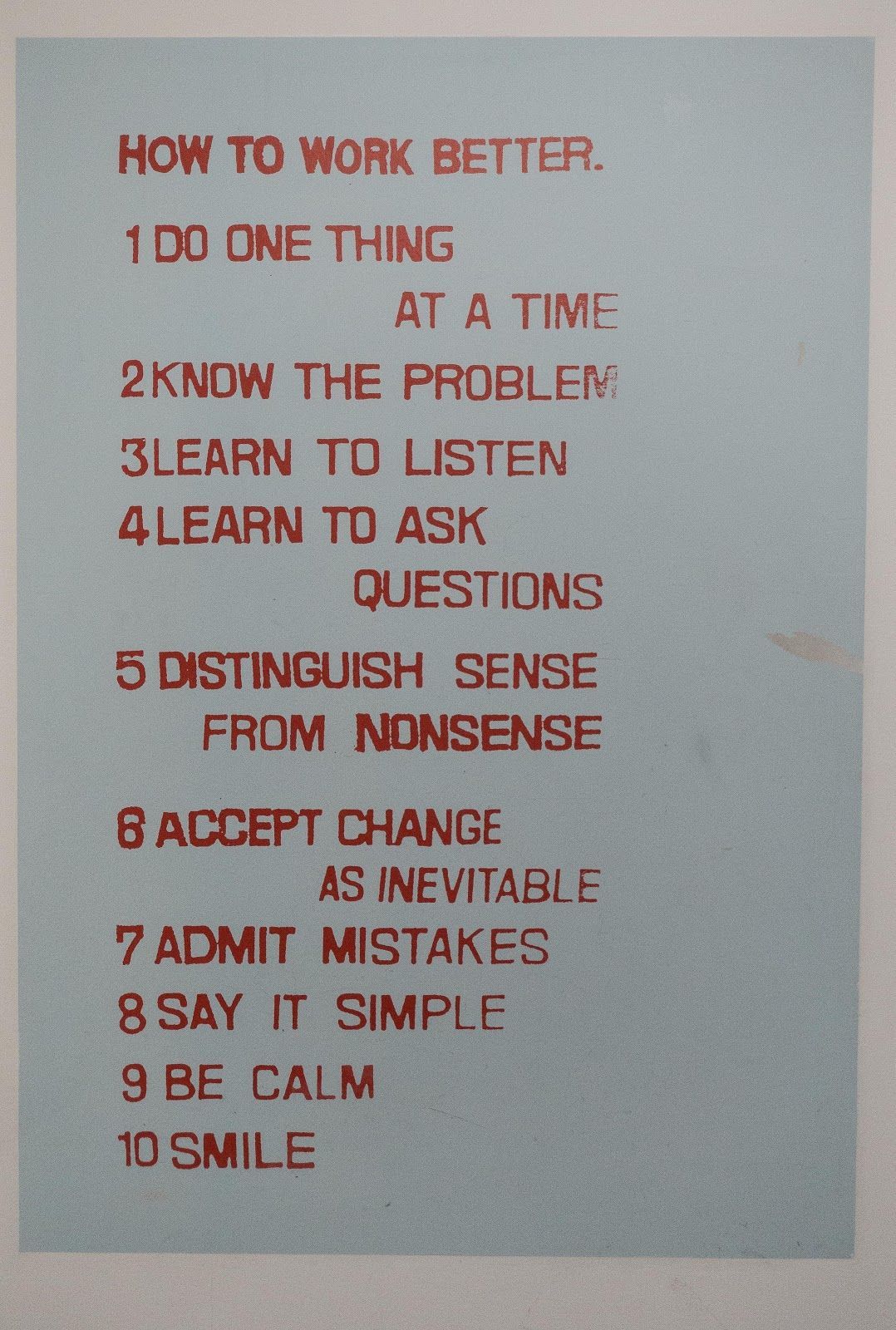

Here’s a photo from a recent performance of Victory:

OK. These weird outfits don’t look much like peasant costumes—but maybe this drawing does a little:

The theater piece leading to the square seems like a perfect example of using an experience in a medium you’re somewhat unfamiliar with to allow oneself to make a breakthrough in one’s primary area of work. Get out of your safety zone and maybe something will happen.

But back to Russian surrealism in daily life.

Brian told a story that during WWI, with so many men on the front, and gone for so long, there existed a situation where marriages had been promised, but couldn’t be fulfilled, as the groom was away fighting a war. However, in many cases, the marriage ceremony went on as planned, but with a hat belonging to the groom placed on a chair, symbolically substituting for the man himself. These were deemed to be legal marriages by the state—an instance of state-sponsored surrealism.

I can’t help but notice the similarity between the nomination of a hat for a man and the nomination of paintings as power items. The substitution of an idea for reality seems ubiquitous.

Another story of acknowledging what isn’t there.

During WWII, the incredible bounty of art stored in the Hermitage Museum in Saint Petersburg was spirited away for safekeeping. Only the big, bulky ornate frames were left hanging on the walls. The guards and docents would still give tours it seems, leading visitors through the galleries while pointing at empty frames—describing the masterworks that weren’t there.

Malevich’s stripped down paintings continue to resurface in unexpected places. They aren’t fading away anytime soon. Here are replicas of them, on easels, functioning as the set for Caetano Veloso’s recent music tour.

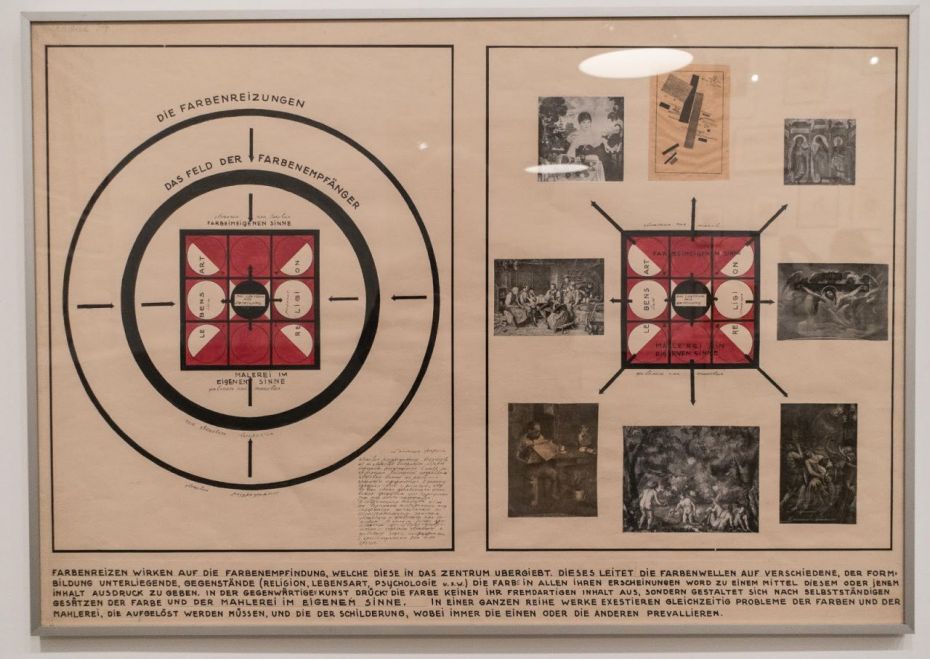

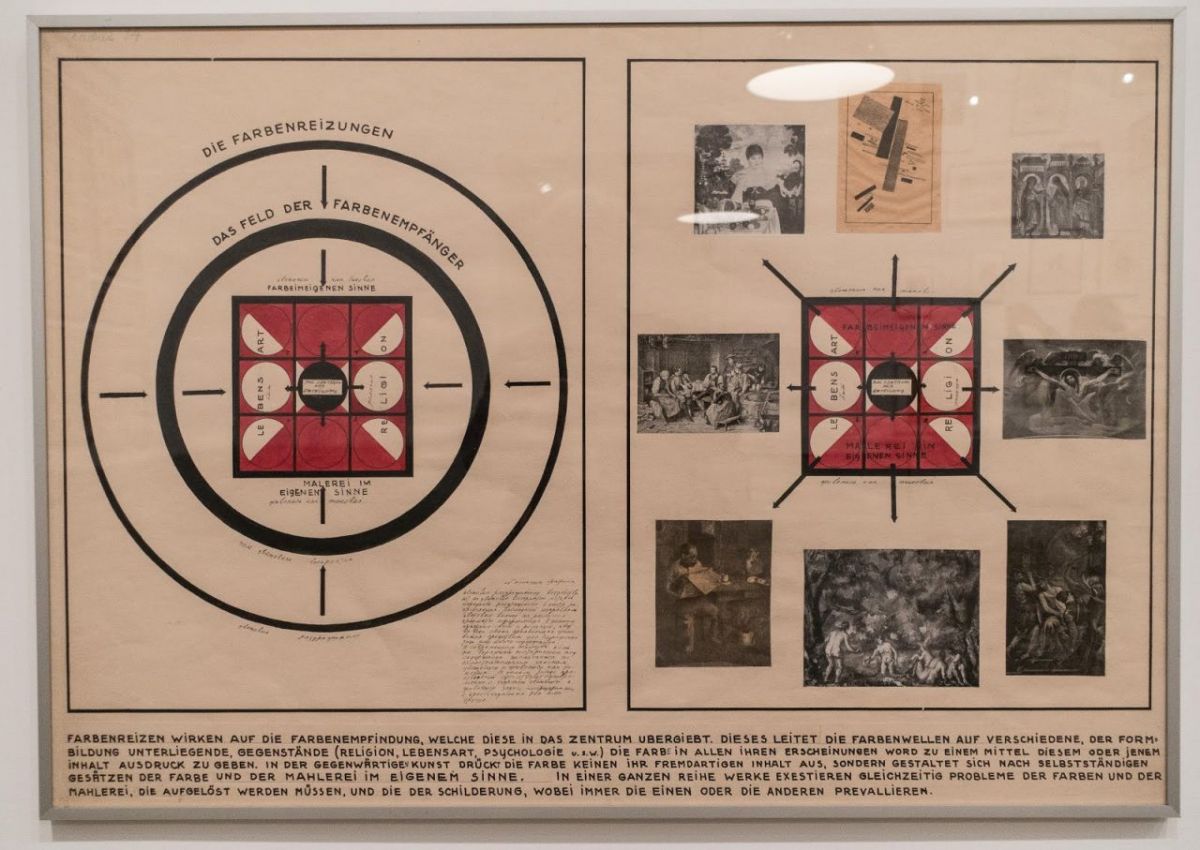

Malevich, like many others of the Russian avant-garde of 100 years ago, was denounced when the Soviet state became a crazy monster. Malevich left Russia briefly for Berlin in 1927, tried to get a teaching job at the Bauhaus but was turned down, and made pedagogical diagrams—in German (where he hoped for employment)—to show how he saw the interconnectedness of many different art forms throughout the centuries. These were a surprise—I’d never heard about them before. If he was forbidden to make his radical work then, I imagine he thought he could at least attempt to impart his ideas to a future generation directly, by teaching.