THE WAY THINGS GO

| July 4, 2016

Flowing Downhill

Lots of artists incorporate images and sounds from popular culture as a way of commenting on it.

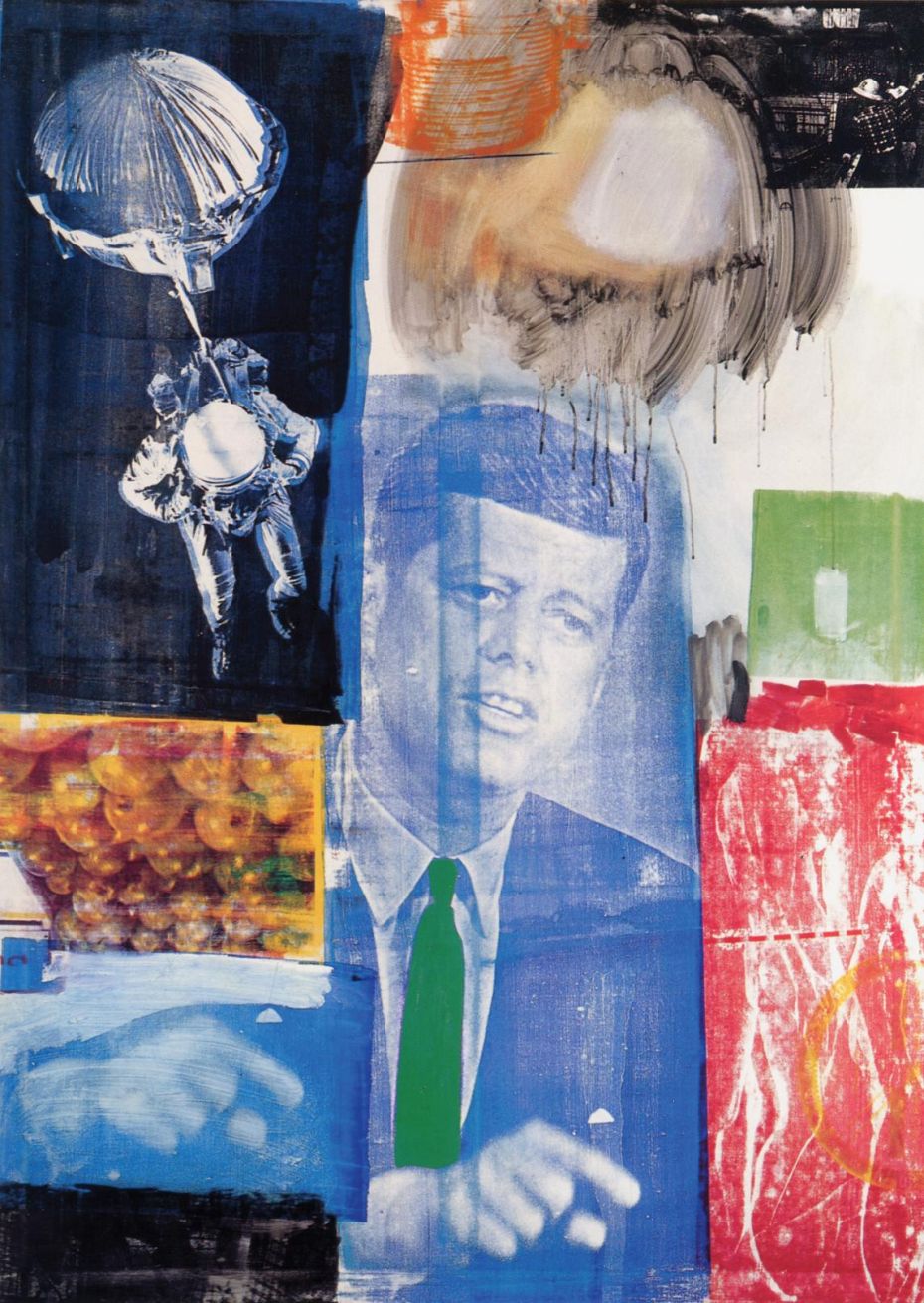

Warhol and Rauschenberg used to appropriate photos from newspapers and magazines for their work—Campbell’s soup was flattered and amused, others not so much, especially when the work started going for serious money. Rauschenberg had some legal issues involving photos he’d grabbed from Life magazine and elsewhere (such as the one below from a news conference about Cuba). Eventually, both artists more or less stopped using found photos altogether—only pics they took themselves. Picasso and Braque used tickets and bits of newspapers, the Surrealists turned to mass-produced prints, even the Romans borrowed from the Greeks—it’s a common technique for an artist to grab from what’s near at hand.

Now more than ever, the world of commercial and mass-produced images are as much our “landscape” as the corn fields were for Van Gogh. Two recent examples especially spring to mind: Kanye West’s new and controversial video for his song “Famous,” and a recent installation at the Sculpture Center in Long Island City by Anthea Hamilton, a young British artist among those shortlisted in May for the Turner Prize. Both bear striking resemblances, intentional or not, to other artworks (including one of particular interest to myself). It is an especially fraught question these days, when so much art is conceptual—more about ideas than images and objects.

The nature of this work, what it was about, therefore changed profoundly due to copyright, IP and legal issues. The work, in many cases, is no longer about the glut of images in our media-saturated landscape… which meant that part of the relationship between the work and the larger culture had been severed.

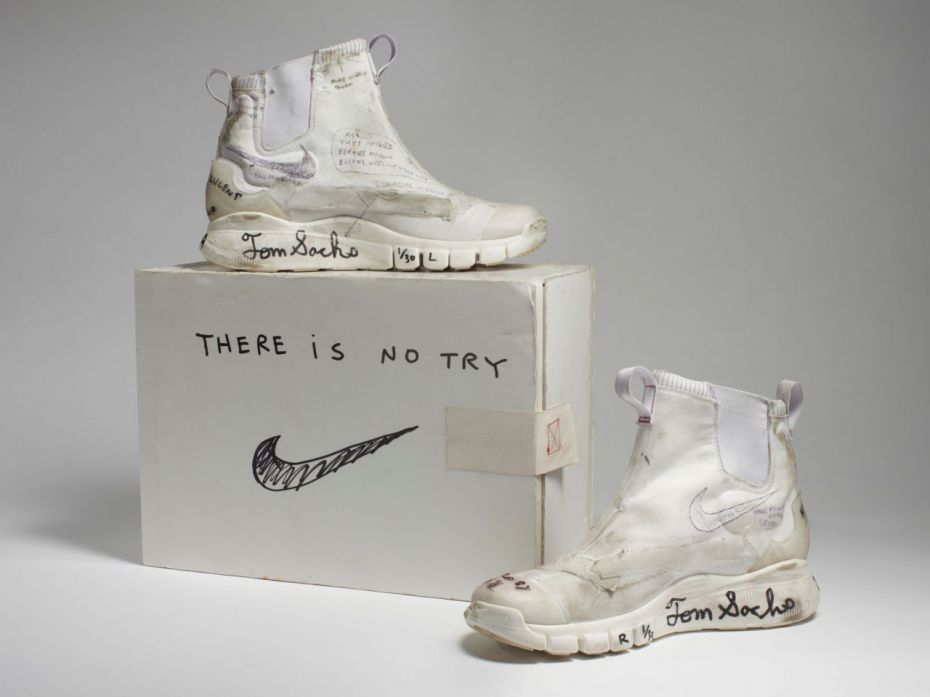

Artists who borrow from commercial and popular culture are not diluting the corporate brand or making money from some confusion—no one thinks Warhol’s soup cans were diminishing the Campbell's brand or that the soup company made less money because folks thought Warhol’s art were Campbell's products. Likewise, there's Tom Sachs’ faux luxury brand copies in unexpected media (which probably now sell for more than that stuff they emulate).

An artist appropriating imagery might comment on President Kennedy, Nike style or other pop culture ephemera, and is, in my opinion, a valid and valuable way of talking about the world we live in. Rauschenberg’s J.F.K. picture was not taking anything away from the photojournalist who took the original. The photojournalist could still license the use of his picture in magazines and newspapers. It’s partly O.K. to use an altered version of this image because we know that it’s the work of a photojournalist and also quite important that the photo was fairly well known. The fact that the image is blue and drippy in Rauschenberg’s case, and with Warhol it’s high contrast and silk screened, heightened the secondhand nature of the image. These techniques were a way of making it obvious that this was a reproduction of a reproduction, and by doing that they referred to that fact, pointing back to the original and the world of mass media, in a way.

If I took this photojournalist’s funny and beautiful image below of The Donald and made it into a painting or a T-shirt I think then it might be questionable. Besides not adding to it sufficiently—like if I added a lightning bolt coming out of the finger—this photo simply reproduced crosses a line. The photojournalist here, as happens increasingly, is also interpreting, commenting, aestheticising in his work. There is artistic expression here, not merely recording.

Flowing Uphill

This borrowing, appropriation and adding to existing work goes in two directions. From grassroots lesser-knowns up to mass culture and commercial applications, and from popular and commercial imagery to “fine art.”

All things being equal, no one would care. But money, as always, makes all the difference, as does credit. When no party benefits more than the other in an exchange, there is less likelihood of there being a conflict. Money, as the song goes, changes everything.

Often it is a successful pop star, movie or video director, or fashion photographer who appropriates a fine artist's work—often an artist who has not yet achieved wide public recognition… or even some who have. Money is inevitably involved—as commercial entities get paid and are about selling us something, not aesthetic and intellectual appreciation. In some cases this appropriation by a more commercial entity is acknowledged, and if the original source is well known, it’s viewed as an homage, sometimes with a wink.

Sometimes ideas and images are lifted by commercial entities without attribution—and one wonders if, in the eyes of those creators, commercial and mainstream work becomes cooler if it harvests from hip unknowns. There seems to be a sense that relatively unknown artists ideas are there for the picking. In fact, it's often viewed as an honor to be picked.

Here’s an appropriation that quite a few folks noticed, in Beyoncé's recent Lemonade film. Someone has conveniently paired the scene in question—the music video for the song “Hold Up”—with a video by Pipilotti Rist, a Swiss artist. Love Beyoncé, but this appropriation does raise some questions about decisions made by Beyoncé or her team to take an artist’s work without obvious credit.

Here’s a video of the two sequences playing simultaneously—pretty much identical, even down to the insouciant look:

Even the above, which some successful artists have said to me in conversation amounts to a simple bit of theft, can be viewed as being more nuanced than it first appears.

A friend who knows Rist told me that with this bit of appropriation going public, suddenly her work and name are becoming known by a wider public. Admittedly, she’s known by this new audience as “the artist that Queen Bey borrowed from,” but some percentage may check her out and find they like what they see. So, from one P.O.V., the “sacrifice” may have been worthwhile. Morally, one might say the copying is wrong, and that doesn’t change, not ever, but in the real world it’s more complicated—Rist may secretly be thrilled.

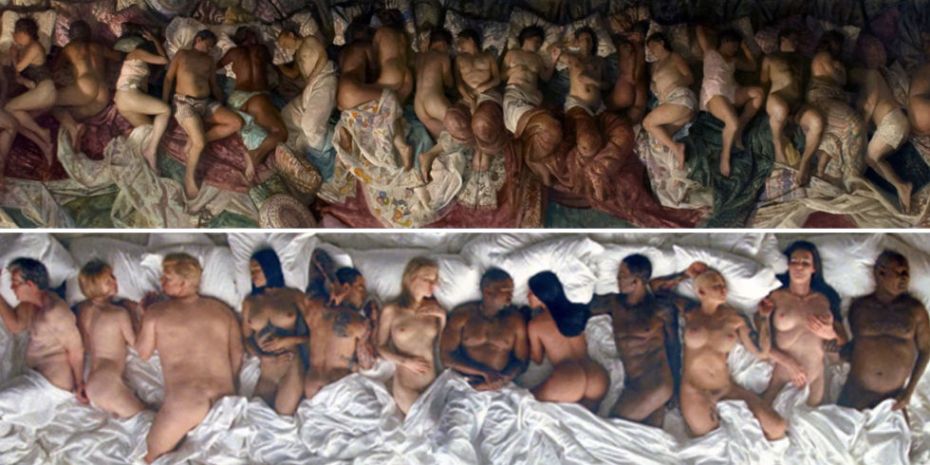

That “thrilled” reaction isn’t unique. Just last week Kanye’s “Famous” video of a mass of naked celebs and politicians all in the same bed was released and it admittedly borrows from the work of a not-too-well-known artist (one I’d never heard of, anyway). Vincent Desiderio is represented by Marlborough Gallery, so he’s probably doing O.K. Even so, Kanye’s team didn’t see blatant appropriation of Desiderio’s image as a problem—absolutely the opposite: after the deed was done, they boldly reached out to the artist and flew him to a meeting where they offered him neither money nor credit. But, to my surprise at least, he was thrilled.

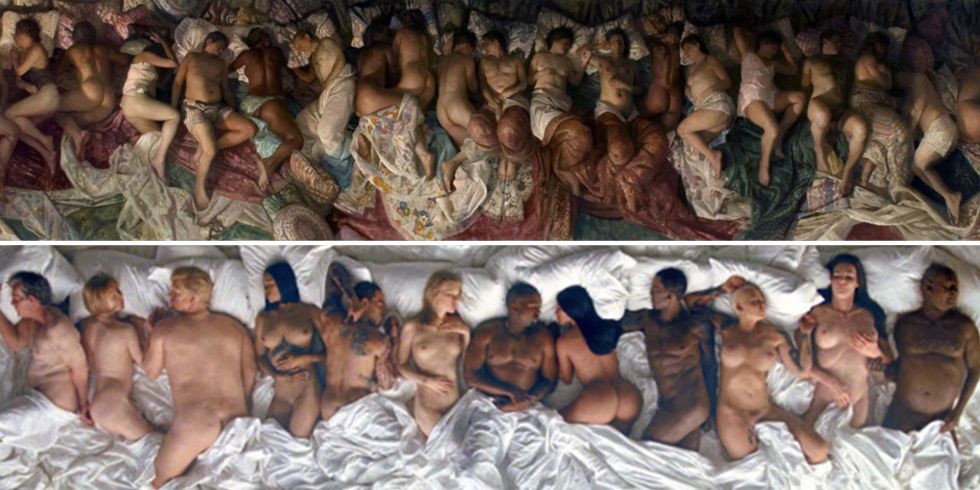

But not every artist feels the same way. Here is a Honda ad made by Wieden+Kennedy that blatantly copies the wonderful film The Way Things Go by artists Fischli/Weiss:

The art film was well known in the advertising industry, and the artists had been approached several times with offers for the right to use the concept, but had always declined. They wrote, complaining, to the agency, but no legal action was taken.

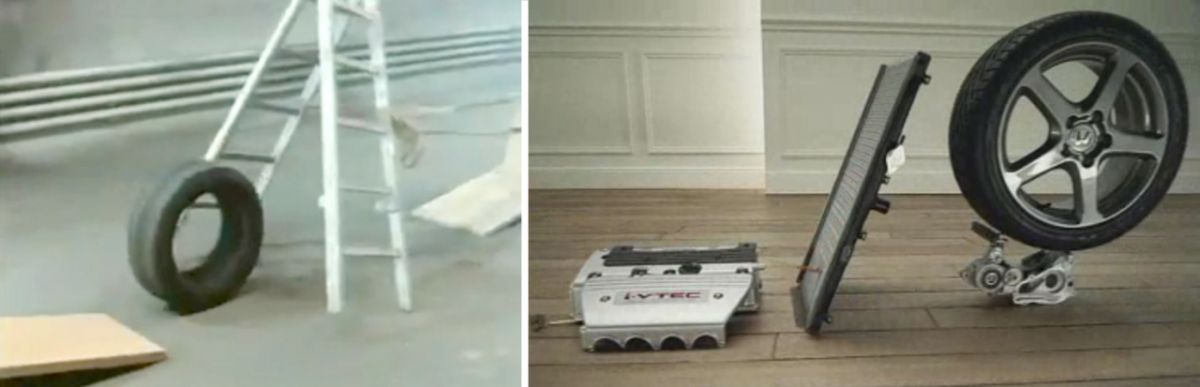

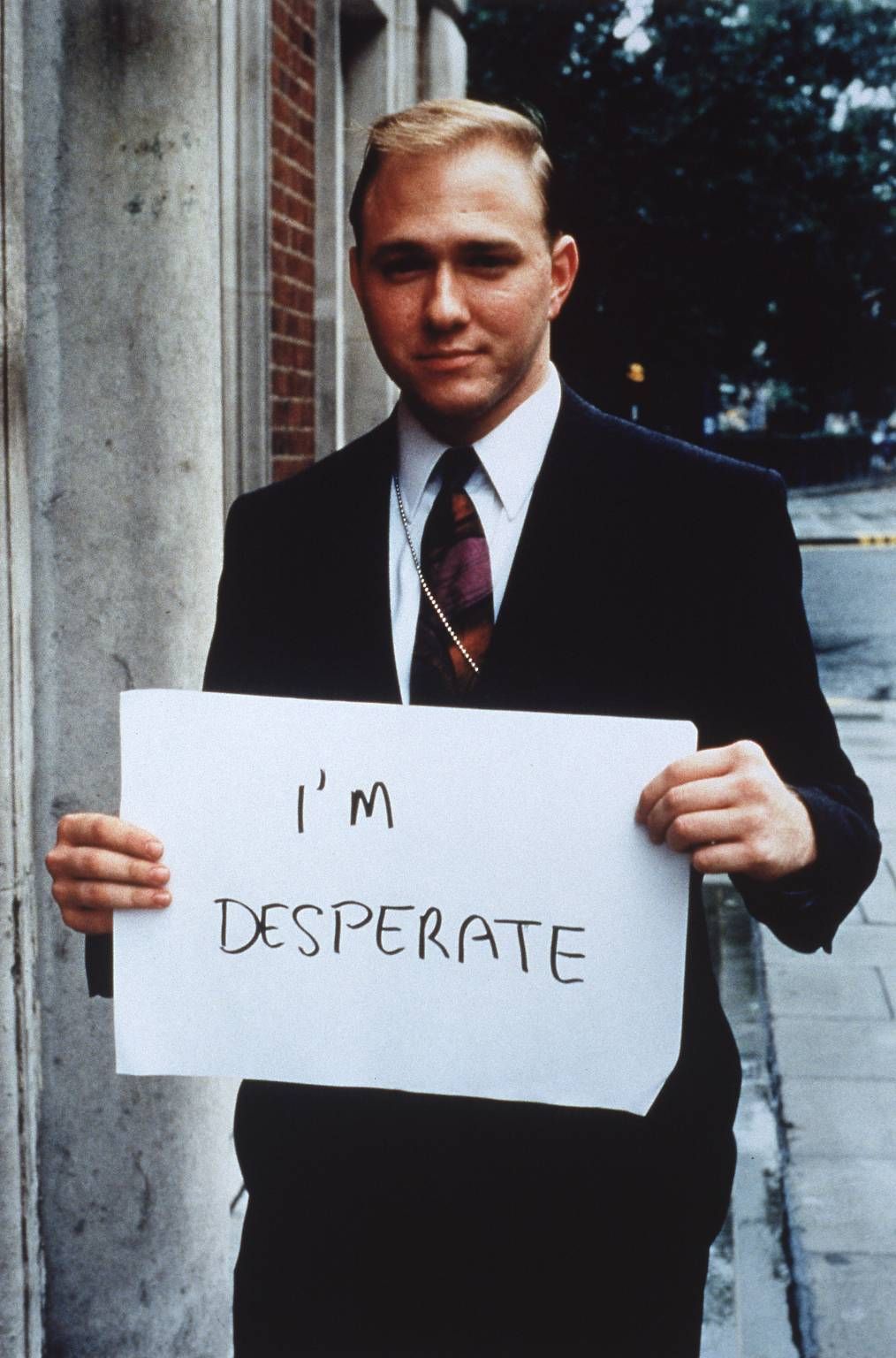

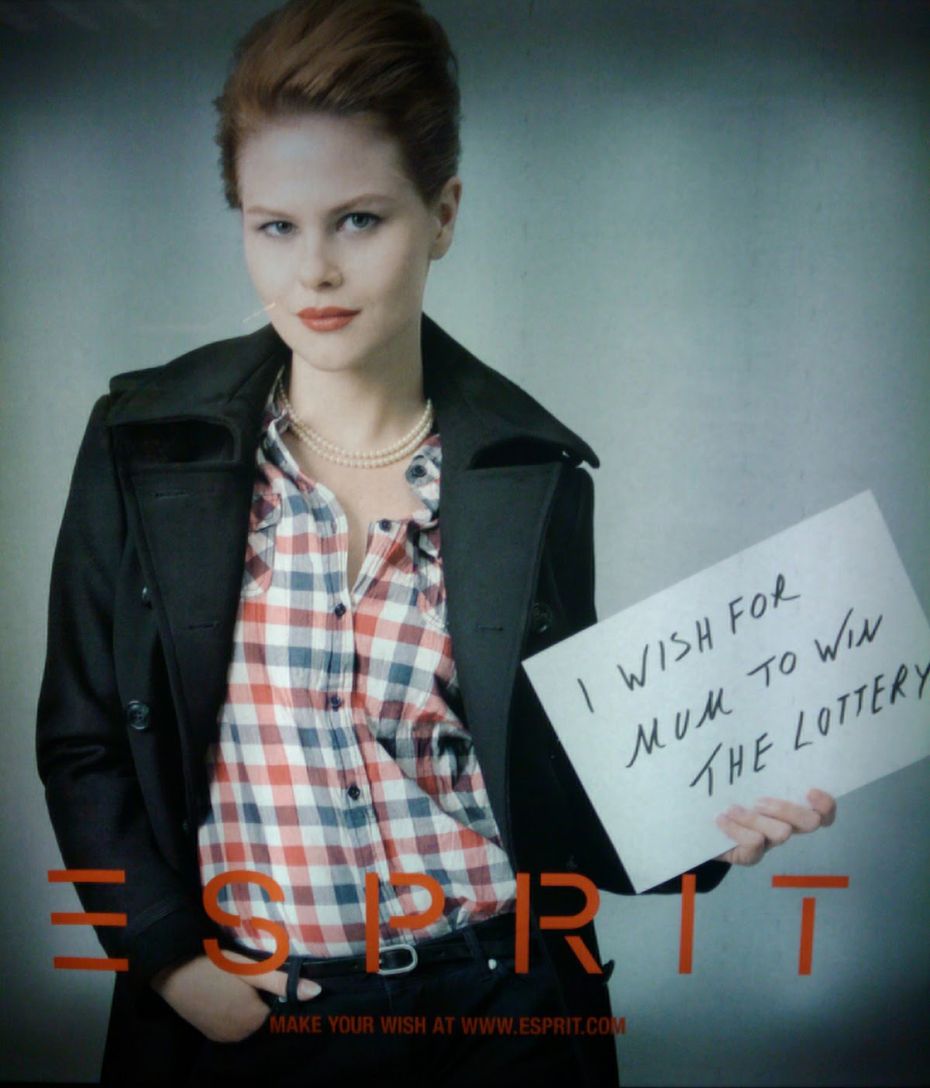

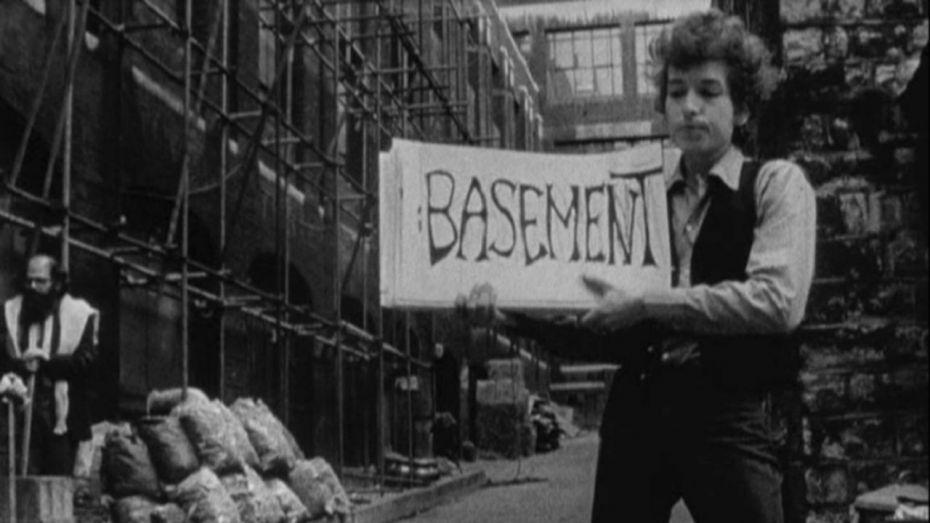

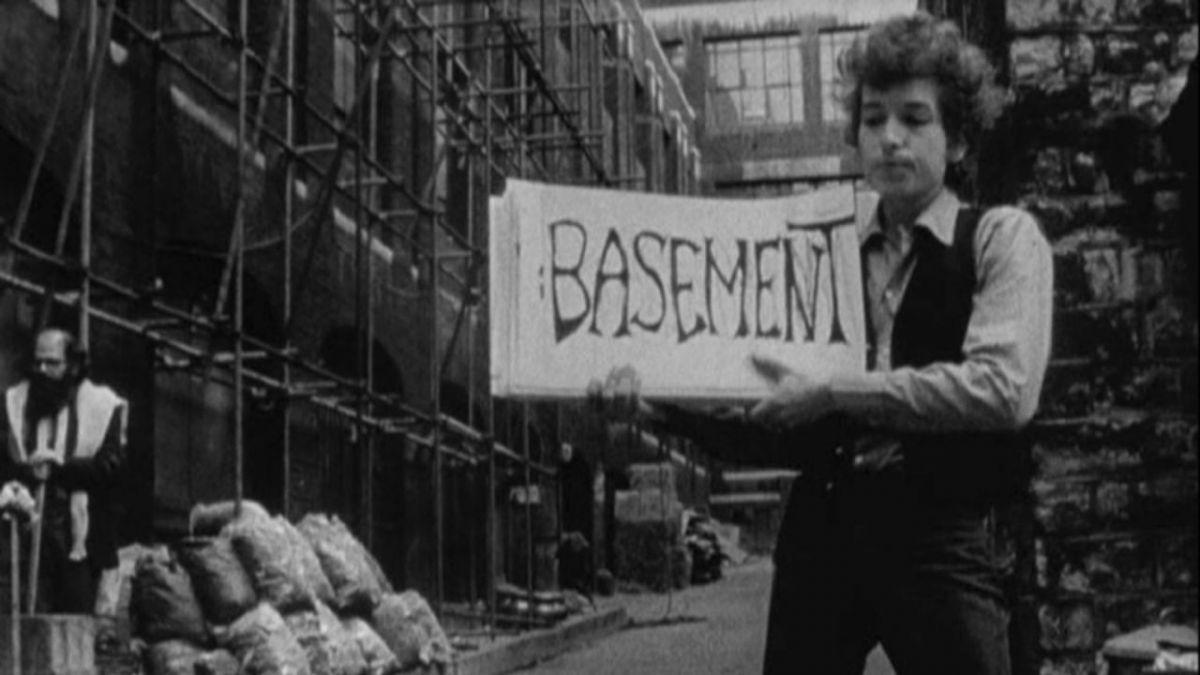

Likewise, the artist Gillian Wearing felt that VW—or the Saatchi agency that created the ad (and whose owner bought her piece!)—had been influenced a little too obviously by her series of people holding cards.

Oddly enough, or not, I can’t find any examples of the VW Golf ads that were “inspired” by this series. But—even more telling—here’s an entirely different campaign from Esprit!

The APEngine has an excellent collection of examples of this kind of creative “borrowing” from artists. The writer on the site even reminds us that the famous opening of D.A. Pennebaker’s Dylan doc Dont Look Back may in turn have been an inspiration for Wearing.

When is a very subtle transformation sufficiently different from copying? One might argue that a black woman smashing cars has a different meaning than an image of a white Swiss woman doing the same thing. And that smashing car windows in New Orleans has a different meaning than smashing them in the orderly world that is Switzerland. I’d argue that folks might indeed interpret the Beyoncé scene as being about the rage of a black woman—whatever the implied circumstances—which is way different than what one might read into Rist’s video. Is that enough of an excuse for the director to appropriate someone else’s work?

If the dress doesn't fit…

Fashion, both in advertising and editorial, is another place rife with and for appropriation, whether scenes from paintings, films or distinctive photography. Take Jim Jarmusch and Jacques Demy films, for example. And similarly there are lifts from lowbrow sources like porn films and amatuer snapshots. Fashion is a real magpie, which is part of the fun and amusement, I suppose…

Do fashionable readers know when images are appropriated? Are they simply winks to insiders? The fashion photographers often get paid much more than some artists but is money an issue in all this? Should it be? if someone makes money off someone else's image, idea, intellectual property… should they rightfully share that money? Or at least give credit? Or offer to collaborate? Or does the cross-media change of context make it a new work?

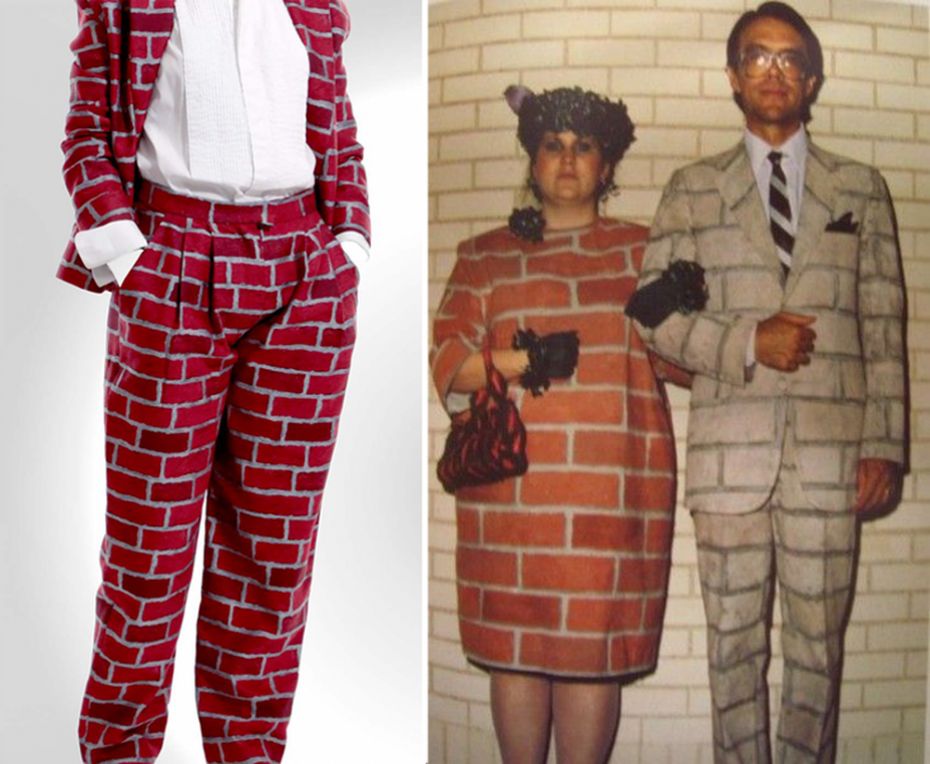

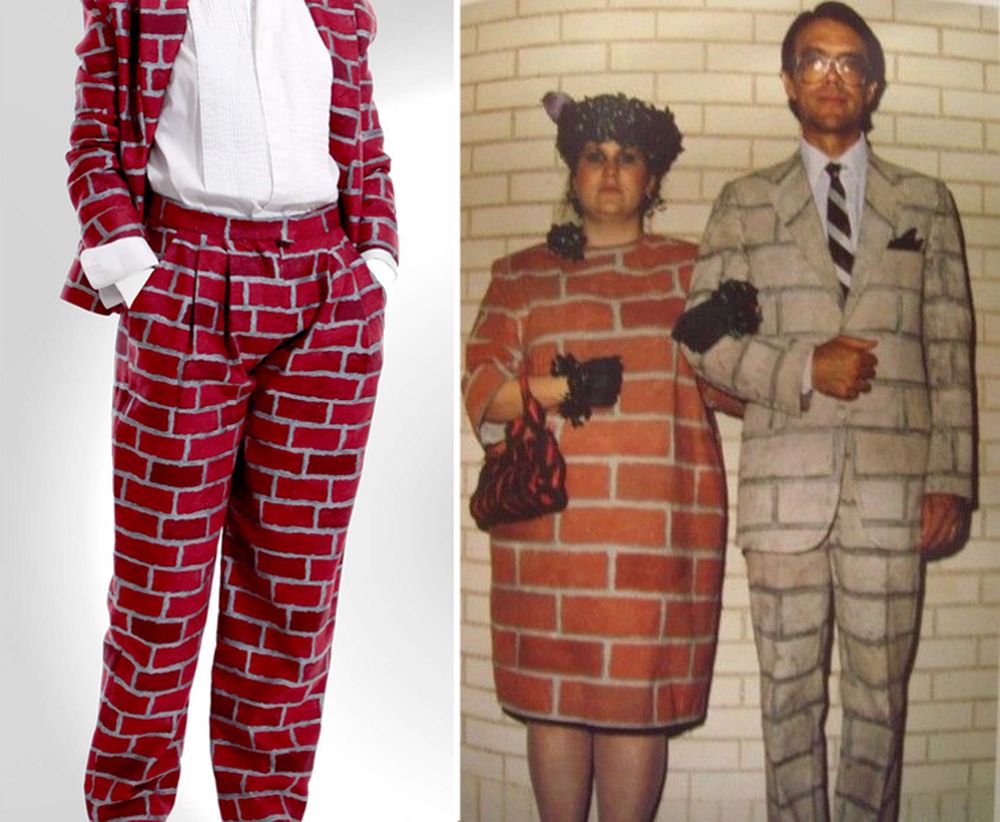

Here’s a case where the artist sued the fashion brand. The graffiti artist John Tierney A.K.A. Rime did this piece in Detroit.

The very talented designer Jeremy Scott later did these outfits for himself and Katy Perry and featured them at the Met Gala.

Moschino is the parent fashion brand for Scott, and their lawyers claimed graffiti is not art, but vandalism… it is illegal and therefore not defensible. The case was settled out of court.

Some lifts can be unconscious and unintentional—it’s always possible that a designer or advertising director saw something as a child, or even last week, and sort of forgot about it. Priming, as this is called in psychology and neuroscience, is a real thing—and it means that one can be influenced by something and not even consciously remember they saw it. You can copy something without even realizing you're copying, the source all but forgotten, except maybe at the most unconscious level.

I would like to think that is what happened with the work pictured below by Anthea Hamilton, among the four artists nominated for the 2016 Turner Prize. It bears a striking resemblance to some costumes that were done for my True Stories movie back in the ‘80s.

I’m probably guilty of unconscious copying myself—though don’t ask me for examples; if they are truly unconscious then I’m not aware of them!

Who’s idea is it anyway?

Can one be guilty of copying someone else’s idea if you don’t remember having heard it or seen it? The law says that it doesn’t matter—if there’s a chance you saw it, then the onus is on you. A person who grew up isolated in a jungle, or somesuch, and could not have possibly seen any of this stuff might be declared innocent, but when does that ever happen?

I would agree there are visual memes and more—there are iconic shapes, patterns and visual relationships that we might all share, like the sun, stars, flowers in a field—regardless of whether we’d ever been to a museum or not. But these days that’s almost a thought experiment. In our media-saturated world, almost all of us have seen fleeting glimpses of so much, both originals and appropriations… and that goes for ideas, too.

It’s all a complicated question, and it seems it’s not as simple as it might seem. I do think that some artists might be undervaluing their own work. Desiderio, whose work Kanye appropriated, is quoted as saying that once the work is out there (the image — and the idea — I imagine) it doesn’t belong to him, the creator, anymore. Seems like a noble and generous gesture on his part.

But maybe that view only works when one only benefits by selling a creation once. Artists, like Desiderio have maybe gotten used to the idea that once their work has been paid for, it’s no longer theirs. The idea and the image are gone into the world. Like Gillian Wearing and Fischli/Weiss, not all feel that way.

That’s a very old idea about art, that it’s an object made for the King or the Church, and once they pay for it, the deal is done. Collectors, too, buy work—which we might call an idea, as well—and then they hide it in the Geneva Free Trade Zone. If the artist got paid well, why should they care?

As we think of creative work more as intellectual property, and less as objects, our ambivalence might change. Creators now often see that their ideas have value, cash value, beyond the one physical iteration they made. That value also increases if more people see and experience the work.

Nothing Comes from Nothing

Picasso is rumored to have said “good artists copy, great artists steal.” But he didn’t. Steve Jobs made up that Picasso quote—hmm, maybe to justify some of his own habits?

But rather than shouting “Theft!” it’s maybe more interesting to ask ourselves how we feel about this. When is something different than something else? If it is different, then is it something new? What aspect of the “original” makes it unique? We like to think of ourselves as being unique, but are we so different than these other kinds of creations? Aren’t we also part of a continuum?

Nothing is truly original. “Nothing comes from nothing,” as a famous songwriter once wrote. Everything is built on the work of those who have gone before. No one invents things from whole cloth. The work of one’s predecessors is added to, tweaked, tinkered with and, very importantly, transformed—whether in the arts, sciences or business. We as individuals don’t emerge out of whole cloth either. Our genes, our communities, our economic circumstances, pure luck—we build ourselves on all of that has gone before us.

Scientists endeavour to share their work. They realize that there is reciprocal benefit and by publishing it, and sharing the data, they also claim credit. At the same time, they often stake an I.P. claim. (Or, increasingly, it is the university or company they work for that stakes the claim.)

The idea that new ideas come about incrementally, by building on the work of others is often attributed to Newton (who famously shared his works in progress with his peers), though it was actually the medieval philosopher Bernard of Chartres who said “We are like dwarves perched on the shoulders of giants.” The giants he meant were his peers and the Greek and Roman philosophers that came before. The implication was that from these elevated heights we can “see” further, though we ourselves are of modest stature.

Building and creating in this way is accepted practice—appropriation is acceptable—if the new creator actually adds to and augments the original idea. It is not just O.K., then. In fact, it is essential to the evolution of creative work and to science.

The law tries to define when a new idea or creation is different from a previous one that is similar. Not an easy thing to define. The law says that to be legal, an appropriation must be transformative. It must be a comment—a critique, a parody or a satire—on the original, and not just a copy. It’s obviously not acceptable if you can’t tell one thing from the other.

But as art increasingly is about ideas and not only images, visual consistency isn’t enough to make two things the same. A thing might not be a mirror image of something else, but still be appropriating its idea or be a new idea. Even just moving something to another context may be transformative all by itself. Duchamp’s urinal, for example. Sometimes it’s hard to prove if the work has actually been substantially reinvented by simply being placed in a new context, but that’s the law. Graffiti printed on a frock, an artist’s video turned into an ad or a promo video for a song? Are those transformative enough?

Am I, just like these things, a different person depending on my context? Most people would say “don’t be crazy,” but it’s not quite as far fetched as it sounds.

We build on the work that others have done before us, so we might at the very least acknowledge them and their work… and maybe sometimes even compensate them. But credit goes a long way. And as a result we—artists, musicians, scientists and mad men—might then end up with things, or become somebody, completely different; we ourselves are ideas elaborated and transformed. And those will in turn be built on, too.

DB

New York City

[Cover image: Tom Sachs, Chanel Chain Saw, 1996, cardboard, thermal adhesive, 12 x 27 x 37 inches, Courtesy of the artist]