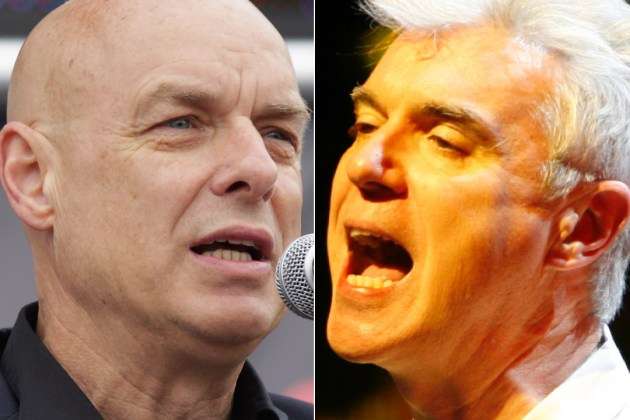

40 Years Ago: Brian Eno Meets David Byrne, Changing the Talking Heads’ Career Path

Oli Scarff / Amy Sussman, Getty Images

Written by Nick DeRiso

Eno‘s remarkable six-album collaboration with David Byrne began with a chance meeting at London’s Rock Garden.

He tagged along with John Cale of the Velvet Underground to a May 1977 concert by the Ramones in which the Talking Heads were serving as the support act. The next day, Eno brought Byrne to his apartment to listen to music.

It was a big-bang moment for the Talking Heads. There, Byrne discovered Afrobeat pioneer Fela Kuti – whose album Afrodisiac worked as a kind of muse for 1980’s Remain in Light. “I was very excited about this music at the time and they were pretty excited too,” Eno told the Guardian in 2009. He described their shared passion for Kuti as “thrilling, because no one in England was at all interested.”

Eno announced he was going to produce the Talking Heads’ next album, even though Cale had already proclaimed the exact same thing. In fact, Eno would eventually work on a trio of the band’s albums, as well as three solo projects by Byrne – two in tandem with these career-making group efforts, and another years later.

This marriage of downtown post-punk rockers and an emerging pioneer in ambient music wasn’t as unlikely as it might have seemed. The Talking Heads, in fact, had been fans of Eno, both with Roxy Music and as a solo artist. Filmmaker Mary Harron recalled that they had the latter-day Roxy Music song “Love Is the Drug” in heavy rotation during an interview she conducted for Punk magazine in 1975; bassist Tina Weymouth also reportedly told her she had gotten into Eno’s Another Green World.

Their first album together was 1978’s More Songs About Buildings and Food, which found the Talking Heads taking embryonic steps toward a more rhythm-focused sound. A cover of Al Green‘s “Take Me to the River” became their first-ever Top 40 hit. Fear of Music, a No. 21 hit, followed in 1979. It kicks off with the absolutely tribal “I Zimbra,” an Eno co-write that provides the first hint of how fruitful this pairing would become on their masterpiece Remain in Light a year later.

“That track was generated from a group improvisation,” Eno told Rolling Stone in 1981. “It was a step forward in a lot of ways. And we suddenly thought, ‘This is really quite close to what we’ve been listening to.’ We realized that we were nearly there, in some sense. It was an interesting piece, but it presented a real dilemma for the Talking Heads in that it was a new format for them. And I really wanted to encourage that.”

Eno had found a group of experimental confederates, in particular with David Byrne. Their angular debut album Talking Heads: 77 only hinted at this growing allegiance to funk and soul. “Eno’s haphazard instinct helped turn the brittle and wary Talking Heads into a supple, playful, Dada-esque dance band,” the New Yorker‘s Sasha Frere-Jones later noted.

Prior to the Remain in Light sessions, Byrne and Eno compiled My Life in the Bush of Ghosts, a wildly inventive solo album that paired these African cadences with a slew of next-gen samples and electronic-music techniques. By the time the Talking Heads reconvened, Byrne and Eno’s shared polyrhythmic vision had crystallized.

Their first-ever Top 40 album and third-consecutive gold-selling smash, Remain in Light tied together all of Byrne and Eno’s recent creative strands – gritty rhythms and crisp electronics, elemental R&B and oddball post-modernism.

Together, they’d created a connective bridge between mainstream pop and the avant garde. Byrne has described the relationship as “mutually beneficial and codependent in a way. We had musical things to gain from one another – each one could offer something slightly different to the other.”

A final classic-era project, 1981’s The Catherine Wheel, found Eno working on three songs for a Byrne musical score commissioned for choreographer Twyla Tharp. By then, however, Byrne’s close relationship with Eno had begun to put a strain on the Talking Heads, and they decided to self-produce the next three albums.

Some 27 years after that, Byrne and Eno released a belated reunion project, 2008’s fizzy Everything That Happens Will Happen Today. Falling back into old completely improvisational habits, they found magic once more. “Eno gave me confidence in the studio,” Byrne told the Independent, “to go in with nothing prepared.”

For Eno, there was a sense of closure in working with Byrne again – but also a reminder of successes together that he could only dream of as an early member of Roxy Music from 1971–73.

“We’d imported a whole lot of ideas that hadn’t been in pop music before and changed the form to fit us,” Eno told the Guardian. “That’s what Talking Heads were doing, too. They took American light funk, people like Hamilton Bohannon, and married it with downtown New York punk or new wave. Now everybody does it, but at the time it was a very new idea.”