Brian Eno and David Byrne reunite in the return of the digital masters

Via Times Online

By Mark Coles

Most people go interrailing around Europe in their late teens or early twenties. Brian Eno has left it until he’s 60.

Clearly taking his new role as youth adviser to the Liberal Democrats very seriously, he’s packing his rucksack. “I can’t wait,” he says. “I love train journeys. I make a lot of my music on trains.”

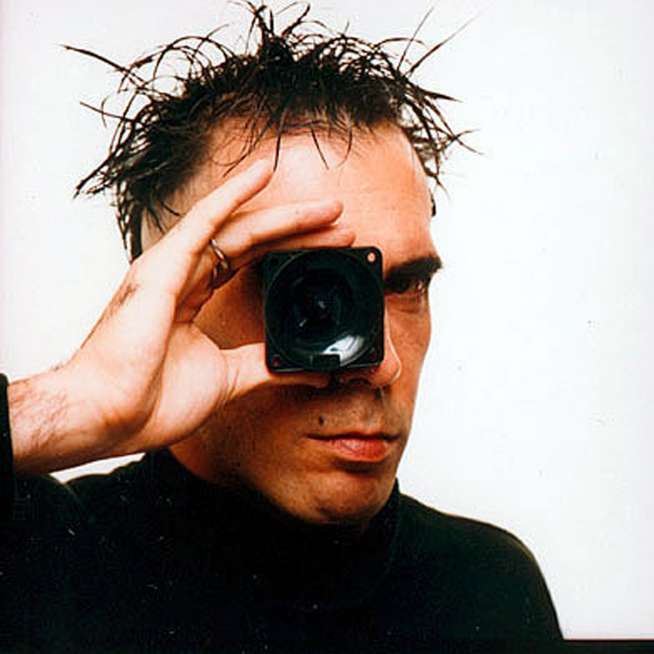

It’s a sprightly Eno who greets me at his homely studio in a West London mews. A black cat is curled up, purring, under the kitchen table. Eno has made a new album with the former Talking Heads singer David Byrne. It’s the first time the two have recorded together since their ground-breaking 1981 album My Life in the Bush of Ghosts. After he produced Coldplay’s multimillion-selling album Viva la Vida, you might expect him to be sitting with his feet up, resting on his laurels. Not Eno.

Dressed in black T-shirt and trousers, a far cry from his Roxy Music days in the 1970s when he wore leopard-print shirts and flared trousers, he has the air of someone who looks after himself. “Anyone for herbal tea?” he asks, before launching into how he and Byrne got together again. “I bumped into David in New York,” he says. “We had dinner together and I happened to say I had a lot of music I had intended to turn into songs, but hadnt got round to. He said: ‘Oh, I’ve got a few lyrics.’ It was as simple as that.”

For the next year or so, working several thousand miles apart, they swapped ideas and music over the internet. Wasn’t that a rather impersonal, unspontaneous way of making music? “No,” he says, looking surprised by the question. “It meant I could spend as long as I wanted on every tedious detail of the music without feeling I was wasting the time of somebody else in the room.”

Their previous collaboration, My Life in the Bush of Ghosts, was unique. There were no songs as such, no vocals, just sampled voices collaged over multilayered percussion. There are those who say that it invented sampling. Kate Bush liked it. “It’s had a huge impact on popular music,” she said back in 1985.

So, did Eno feel the weight of history when he teamed up with Byrne again? “No, this is quite different from My Life in that the intention of that album was to not use our voices at all, but instead to find voices and stick them on to the music. This new one is different – these are songs written and sung by David. They cover quite a range. They go from electronic folk gospel to quite indefinable areas of music.”

Eno was born Brian Peter George St John le Baptiste de la Salle Eno in Woodbridge, Suffolk, in 1948. He went to art school, became the keyboard player in Roxy Music before going solo, turning his hand to abstract soundscapes, earning the title “father of ambient music”. There have been other ventures: video and art installations, a deck of “art cards” designed to to break creative block. But it’s his work in pop music that has given Eno his greatest commercial success. He has worked with David Bowie, U2, James, Paul Simon and, most recently, Coldplay.

Fearful of his new collaboration with Byrne leaking on to the internet, someone at the US end of things has ordered Eno not to give me access to the music. “Corporate American paranoia,” he mutters. The only solution is for me to record him playing chunks of the album from his laptop as he talks over the tracks.

The album is called Everything that Happens Will Happen Today. One of the 11 tracks, Strange Overtones, “a song about writing a song”, was made available as a free download single on Monday. The album is released digitally this month.

“One of the tracks, I Feel My Stuff, is unlike any other song I’ve ever heard before,” Eno says. “This is real abstract territory. I guess David’s never quite sung over music like this before. I thought it’d be a real challenge for him to turn it into a song. But he did.” The song features avant-garde piano, ominous-sounding bass and vocal percussion before Byrne’s lyric floats in over the top.

“His voice is beautiful at the moment,” Eno says. “I think it’s better than it’s ever been. There’s a tenderness as well as that spiky, geeky thing it had in the past. He sees the world differently from the rest of us.” One song, One Fine Day, has already been performed in the US by a choir of elderly people. “David conducted them. Their average age was 80. He said it was very touching to hear them singing a song about optimism for the future at their age.”

Others are more conventional. Life Is Long features the lyric: “Everyone says the living is easy, but I can hardly see ’coz my head is in the way. I’m lost, but I’m not afraid.” “It is a gospel song written by two atheists,” Eno says.

He adds: “Without even discussing it that much, we shared a feeling about what kind of record this should be. We both wanted to make an album that combined something human, fallible and personal with something very electronic and mathematical. We wanted to paint a picture of the human trying to survive in an increasingly digital world.” Which sounds a bit Radiohead, both in sentiment and in the way that the album is being released via the internet before it comes out on CD. “Yes. It’s deliberate,” Eno says. “I’ve noticed that I’ve stopped buying CDs”.

But surely the huge sales of the Coldplay album proved that the CD format wasn’t dead? “It’s changing. There are lots of new ways you hear about music now. I hardly go into record shops any more. I buy from iTunes.”

On his website Byrne goes one farther. “In the past, I might have undertaken all kinds of expensive marketing plans to prepare for a record release. It’s going to be interesting to see if audiences find out about this record solely through internet word-of-mouth.”

Why does Eno think he works so well with Byrne? “It’s basically because we’re old arts students. We have a slightly different interest in music than nonarts students do. We’re interested in the gestural and art historical position that these things occupy. We’re always listening to other things to see if we can stick them together to make something new.”

And next? “I’m writing a book.” What sort of book? “I’d rather not say until it’s finished.”

A well-thumbed book about disaster capitalism on his desk suggests that it might be a serious one. Beside it are a pile of new gadgets he’s taking on his trip. “I’m going to finish the book on the train and compose some music,” he says. “In my laptop I have a recording studio. I’ve got this new microphone for capturing sounds around me. I can construct instruments and play them on the train, which always gives fellow passengers cause for alarm.”

If you’re interrailing around Europe this summer, watch out for the man in black with the headphones on. You might just end up on his next album.

Everything that Happens Will Happen Today is released digitally on August 18 viaeverythingthathappens.com. A CD version will be released in October.

Mark Coles is a BBC World Service presenter.