Everything That Will Happen In The Music Business’ Future May Have Happened To Eno And Byrne

Via Idolator

By Lucas Jensen

Count me among those instantly skeptical of any new business startup that has anything to do with the music industry, particularly as 2009 approaches. Heckfire, I was instantly skeptical of these nebulous businesses in the late '90s, when, as a music industry professional and a musician, I was bombarded with offers of liaising and support systems and synergizing by companies that probably had basketball courts in their offices and went bankrupt six months later. So when I read something like this on the site for the digital-music startup Topspin, it's hard not to get a high reading on the BS Detector:

Topspin is a media technology company dedicated to developing leading-edge marketing software and services that help artists and their partners build businesses and brands. We help artists manage their catalogs, connect with fans, and generate demand for music.

Ian C. Rogers is at the "helm" (their wording, not mine) of the aforementioned company, and he was thekeynote speaker at *ahem* the GRAMMY Northwest MusicTech Summit 2008. Doesn't that soundexciting? Nothing gets me more excited than uselessly crammed-together words like "MusicTech" combined with GRAMMY written in ALL CAPS. But Mr. Rogers actually had some interesting stuff to say about the state of the industry, particularly in relationship to the recent David Byrne/Brian Eno collaboration, Everything That Happens Will Happen Today.

Rogers is a former Yahoo! Music GM, but I wouldn't hold that against him. He sees the writing on the wall like most people (well, except those in the executive suites at major labels) do:

The backdrop, of course, is one we know well, a story we’ve heard ad nauseum at this point. Physical sales are decreasing (~20% Y/Y). The “two hit songs for $17 at Best Buy” business is over. Digital sales are increasing (~40% Y/Y) but it’s not making up the difference. Not only is digital not making up for physical sales, as the tracks are unbundled and the model is a singles-driven iTunes business, the actual value of a unit of music continues to plummet.

Indeed. Rogers says that the death of the CD is different than the death of the cassette because the power is transferring to artists and fans rather from one big company to another. While I might quibble about this a bit—I would never count big media conglomerates out of anything—I appreciate him putting this power shift in terms of artists instead of the usual mouth-breathing "music should be free" Digg crowd. I also appreciate his sanguine outlook on music consumption, though he seems to be upselling people's willingness to pay for music, given that he's not examining long-term interest. Ask some teenagers if they ever pay for music and they will scoff at you. Trust me. I posed that question last week at a high school, and I was met with a quick, simple, and derisive response: "Why?"

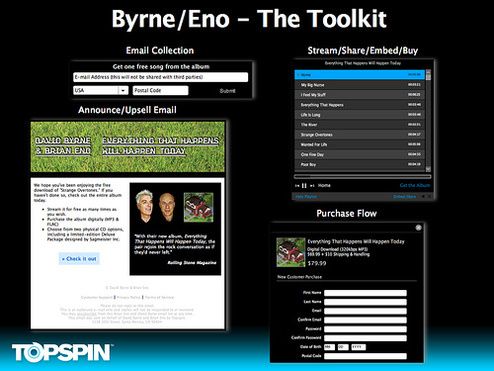

No matter. What interested me most about Rogers' keynote were his observations on Everything That Happens Will Happen Today. Topspin created a page where interested listeners can stream and embed the album anywhere, which is pretty doggone neat. They offered a free track to fans in exchange for an e-mail address, and then gave three album-purchase options for people who wanted to buy the album before it hit iTunes and brick-and-mortar retail: a digital download for nine bucks, a digital download/CD combo deal for $13, and a fancy boxed set for $70. (Those prices are a tad high for my tastes, but I'll let 'em slide.)

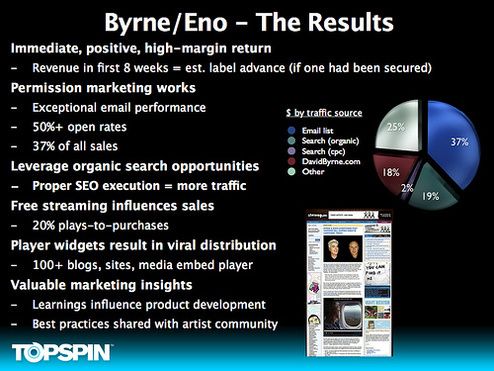

And the project did quite well, thank you very much. Topspin asked Byrne's manager how he'd define success and he gave a figure (unfortunately not revealed here) for what a theoretical record advance would be. That amount was grossed after eight weeks, well before the physical CDs were available. Also, the permission marketing campaign of gathering e-mails worked as well: 50% of people who received them opened them, and, even better, the plays of the embedded album led to purchases 20% of the time. I know what you're saying: this is a unique circumstance given it's Byrne and Eno's first collaboration in 30 years and only the super-fans probably bought it. But isn't that the point? Shouldn't you target the superfans first? Rogers mentioned the movement from high yield, low margin sales (like albums discounted really deeply at big-box stores) to low yield, high margin sales (like specialized packaging options for people willing to plunk down a lot of money), and noted that should artists target these superfans, they'll likely take more money home doing so. Forget the pay-what-you-will model for Radiohead and Nine Inch Nails. That stuff was fun and all, but it's not the real shift in business. The important aspect of those schemes was that they allowed fans and artists to cut out the middleman.

Regardless of whether Topspin Media succeeds or not (and I like this embeddable player thingy), I suspect this early preorder/order-directly-from-the-band model will keep growing. I wonder if superfans are wary of participating in traditional retail schemes because we don't want to see our money going into the hands of the same people who have been feeding us crap—and screwing artists—for years; it's satisfying as a fan to know that your money is going directly to the band you support. People aren't consciously sticking it to the man, per se, but there is a lingering bit of that in their economic decisions, coupled with the ease of attaining free music out there.

One of the problems with the "$17 for two songs at Best Buy" model was always the hubristic pricing of the product sold, regardless of quality. When CD burners went mainstream, people finally understood how cheap each CD was to produce. A nation of music-buyers stood up and asked, "I can buy a spindle of 50 CDs for $15 and the new 50 Cent is $18.98 at Borders?" Consumers aren't that stupid. They knew they were staring right at the price of myopic management, crazy accounting, and out-of-control egos. As an artist and someone who understands that records still cost money to make, even in the home-recording era, I hope that this breakdown of middlemen and labels does mean larger yields for artists. Certainly these numbers give me a bit of hope where my conversations with teenagers do not.