Over the course of three nights at Hollywood's Pantages Theater in December 1983, filmmaker Jonathan Demme joined creative forces with cinematographer Jordan Cronenweth and Talking Heads... and miracles occurred. Following a staging concept by singer-guitarist David Byrne, this euphoric concert film transcends that all-too-limited genre to become the greatest film of its kind. A guaranteed cure for anyone's blues, it's a celebration of music that never grows old, fueled by the polyrhythmic pop-funk precision that was a Talking Heads trademark, and lit from within by the geeky supernova that is David Byrne.

“Three Cheers” By Pauline Kael, The New Yorker, November 26, 1984

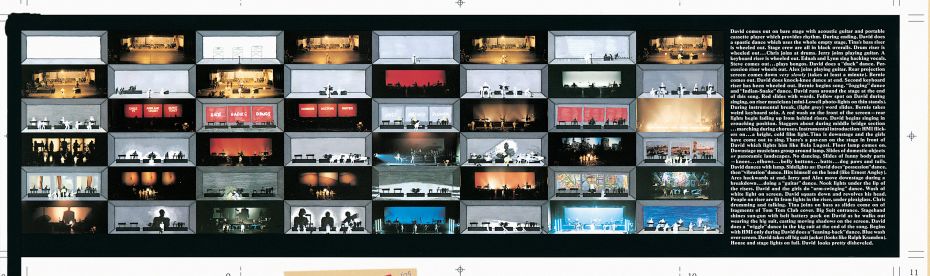

“Stop Making Sense” makes wonderful sense. A concert film by the New York new-wave rock band Talking Heads, it was shot during three performances at the Hollywood Pantages Theatre in December, 1983, and the footage has been put together without interviews and with very few cutaways. The director, Jonathan Demme, offers us a continuous rock experience that keeps building, becoming ever more intense and euphoric. This has not been a year when American movies overflowed with happiness; there was some in “Splash”, and there’s quite a lot in “All of Me”—especially in its last, dancing minutes. “Stop Making Sense” is the only current movie that’s a dose of happiness from beginning to end. The lead singer, David Byrne, designed the stage lighting and the elegantly plain performance-art environments (three screens used for backlit side projections); there’s no glitter, no sleaze. The musicians aren’t trying to show us how hot they are; the women in the group aren’t there to show us some skin. Seeing the movie is like going to an austere orgy—which turns out to be just what you wanted.

Clean-shaven, with short hair, slicked back, and wearing white sneakers and a light-colored suit, with his shirt buttoned right up to his Adam’s apple, the gaunt David Byrne, who founded the group, comes on alone (with his acoustic guitar and a tape player) for the first number “Psycho Killer.” He’s so white he’s almost mock-white, and so are his jerky, long-necked, mechanical-man movements. He seems fleshless, bloodless; he might almost be a black man’s parody of how a clean-cut white man moves. But Byrne himself is the parodist, and he commands the stage by his hollow-eyed, frosty verve. Byrne’s voice isn’t a singer’s voice—it doesn’t have the resonance. It’s more like a shouter’s or chanter’s voice, with an emotional carryover—a faintly metallic wail—and you might expect it to get strained or tired. But his voice never seems to crack or weaken, and he’s always in motion—jiggling, aerobic walking, jumping, dancing. (They shade into each other.) Byrne has a withdrawn, disembodied, sci-fi quality, and though there’s something unknowable and almost autistic about him, he makes autism fun. He gives the group its modernism—the undertone of repressed hysteria, which he somehow blends with freshness and adventurousness and a driving beat. When he comes on wearing a boxlike “big suit”—his body lost inside this form that sticks out around him like the costumes in Noh plays, or like Beuys’ large suit of felt that hangs of a wall—it’s a perfect psychological fit. He’s a handsome, freaky golem. When he dances, It isn’t as if he were moving the suit—the suit seems to move him. And this big box that encloses him is only an exaggeration of his regular nerd-dandy clothes. Byrne may not be human (he rejects ordinary, show-biz forms of ingratiation, such as smiling), but he’s a stupefying performer—he even bobs his head like a chicken, in time to the music.

After Byrne’s solo, the eight other members of the group come on gradually, by ones and twos, in the order in which they originally joined up with him, so you see the band take form. Tina Weymouth, the bass player, who also sings, comes on next; a sunny, radiant woman with long blond hair, she’s smiling and relaxed. (She couldn’t be more unlike Byrne—he’s bones, she’s flesh.) Watching her, you feel she’s doing what she wants to do. And that’s how it is with the drummer, Chris Frantz, and the keyboard man, Jerry Harrison, and the others in the sexually integrated, racially integrated group. The seven musicians and the two women who provide vocal backing interact without making a point of it; you feel that they like working together, and that if they’re sweating they’re sweating for themselves, for their pleasure in keeping the music going. They’re not suffering for us; they’re sharing their good times with us. This band is different from the rock groups that go in for charismatic lighting and sign of love and/or sex. David Byrne dances in the guise of a revved-up catatonic; he’s an idea man, an aesthetician who works in the modern mode of scary, catatonic irony. That’s what he emanates. Yet when the other Talking Heads are up there with him for a song such as “Once in a Lifetime” the tension and interplay are warm—they’re even beatific. The group encompasses Byrne’s art-rock solitariness and the dissociation effects in the spare—somewhat Godardian—staging. The others don’t’ come together with Byrne, but the music comes together. And there’s more vitality and fervor and rhythmic dance Ion the stage than there is with the groups that whip themselves through the motions of sexual arousal and frenzy, and try to set the theatre ablaze.

It’s slightly puzzling that this band’s music absorbs many influences—notably African tribal music and gospel (the climactic number here is “Take Me to the River”)—yet doesn’t have much variety. The insistent beat (it stays much the same) works to the movie’s advantage, though. The pulse of the music gives the film a thrilling kind of unity. And Demme, by barely indicating the visual presence of the audience until the end, intensifies the closed-off, hermetic feeling. His decision to keep the camerawork steady (the cinematographer, Jordan Cronenweth, used six mounted cameras, one hand-held, and one Panaglide) and to avoid hotsy-totsy, MTV-style editing concentrates our attention to the performers and the music. The only letdown in energy, I thought, was in Byrne’s one bow to variety—when he left the stage for the Tom Tom Club number. It’s a likable number on its own, but it breaks the musical flow. (It’s also the only number with a cluttered background, and it has a few seconds of banal strobe visuals.) One image in the film also stuck in my craw: a shot of a little boy in the audience holding up his white stuffed unicorn. It’s just too wholesome a comment on the music. But these are piddling flaws. The movie was made on money ($800,000) that was raised by the group itself, and its form was set by aesthetic considerations rather than a series of marketing decisions. (This is not merely a rock concert without show-biz glitz; it’s also a rock-concert movie that doesn’t try for visual glitz.) Many different choices could have been made in the shooting and the editing, and maybe someone of them might have given the individual numbers (there are sixteen) more modulation, but in its own terms “Stop Making Sense” is close to perfection.

The sound engineering is superb. The sound seems better than live sound; it is better—it has been filtered and mixed and fussed over, so that it achieves ideal clarity. (The soundtrack-album versions of some of the songs that are also on the Heads’ 1983 album “Speaking in Tongues” are more up, more joyous.) The nine Talking Heads give the best kind of controlled performance—the kind in which everyone is loose. At the end of the concert, they’re still in control, but they’re carried away. And Jonathan Demme appears to have worked in exactly the same spirit.