A 'TALKING HEAD' COLLABORATES WITH TWYLA THARP

A 'TALKING HEAD' COLLABORATES WITH TWYLA THARP

By ROBERT PALMER for The New York Times

Published: September 20, 1981

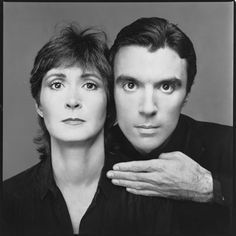

The rock band Talking Heads made their reputation with dance music, but ''The Catherine Wheel,'' the collaboration between the Talking Heads's composer and lead singer, David Byrne, and the choreographer and dancer Twyla Tharp, is dance music of another sort. ''I've found myself working with a lot of rhythms that I wouldn't picture in a dance club,'' Mr. Byrne remarked recently as he hovered intently over a recording studio console and did a kind of jerky, back-and-forth dance to the rich mesh of African percussion, guitars, synthesizers, and multiple bass lines he was adding the final touches to. ''Certain rhythms make your body move the way you move in a club, and in this case I was working with a much greater variety of dance movements, some of which would be really inappropriate in clubs. Sometimes I feel a little odd about this music, but only when I'm wondering how people would react if I put some of it out on an album.''

The Byrne-Tharp collaboration will have its world premiere at the Winter Garden on Tuesday, and it will be performed 11 more times in the course of Miss Tharp's Broadway season, which is to run through Oct. l8th. Composing the evening-long work was a new experience for Mr. Byrne, wh ose most recent recordings with the Talking Heads have been marked b y his growing fascination with West African and black American funk rhythms. And commissioning the piece and working on it with Mr. Byrn e was a new experience for Twyla Tharp, who was, in effect, commi ssioning one of rock's most adventurous composers to write and rec ord almost two albums worth of new music.

''My company has never done anything as complicated as this,'' Miss Tharp remarked as she sat comfortably on the carpet in the recording studio, where she had come to watch Mr. Byrne work after putting in a full day rehearsing her dancers. ''We've been working on it for five months, which is a big commitment. And it's been great. I don't think I'd ever want to use previously recorded music to make a new piece again. Older music has all its connotations in place; everyone knows what they think about it. I've heard David's music before, but it's not the same as hearing this music.''

Several of Miss Tharp's earlier pieces that involved rock music will be performed during her upcoming Broadway season,including ''Short Stories,'' which was choreographed to songs by Bruce Springsteen and Supertramp, and ''Deuce Coupe,'' which features songs by the Beach Boys. But these pieces all involve rock of a traditional sort - short, tuneful songs set to driving, relatively uncomplicated rhythms. Talking Heads's music can still be tuneful and driving, and the group has enjoyed some substantial commercial successes. But recently, David Byrne's interests have been shifting away from conventional song forms and the big beat. He has become interested in complex rhythms and polyrhythms, and not just for their musical value. In West African and many African-derived cultures, the complex interlocking of rhythms in dance music both symbolizes and promotes the welding of a complex of individuals and social forces into a unified community.

Mr. Byrne's interest in rhythm and community was stimulated by ''African Rhythm and African Sensibility,'' a book written by the musicologist John Miller Chernoff and published in l979 by the University of Chicago Press. Mr. Chernoff spent five years in Ghana learning some of Africa's most complex drumming rhythms, and in his book he used his understanding of these rhythms as a key to unlock the rich social and cultural life of the people with whom he studied. Mr. Chernoff's explanations of how African polyrhythms fit together and of the social harmony they both represent and encourage were important influences on both ''Remain in Light,'' the most recent Talking Heads album, and ''My Life in the Bush of Ghosts,'' an album composed jointly by Mr. Byrne and the rock composer and producer Brian Eno.

The music Mr. Byrne composed and recorded for ''The Catherine Wheel'' takes his interest in African rhythms a step further. John Miller Chernoff played African percussion instruments on many of the recording sessions, and according to Mr. Byrne ''he generated the rhythms, or combinations of rhythms, for a lot of the pieces.'' Over these African rhythms, which were played on piano and guitar as well as on percussion instruments, Mr. Byrne constructed a wonderfully atmospheric, multi-layered recording that blends electronics, a variety of unconventional instruments (including a pan half-full of water that was played by Miss Tharp), guitars and basses and, on several pieces, lyrics and vocals. Other players who contributed to the music, which will be heard on tape when ''The Catherine Wheel'' is performed, included the Talking Heads's Jer ry Harrison and severalof the band's recent collaborators, two of wh om are Brian Eno and thekeyboard player Bernie Worrell.

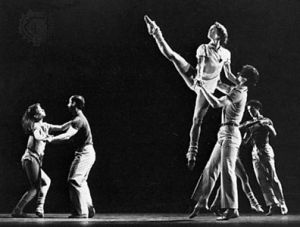

When they began their collaboration, Mr. Byrne and Miss Tharp announced that one of the themes they would be working with was a vision of ''the horrible family.'' A Catherine Wheel is both a kind of fireworks display that is spun by hand and an instrument of torture, and the beginning of the piece does seem to depict a family whose members torture each other. The first image is of a pineapple, but the pineapple is also the same shape as one of the first atomic bombs. Fireworks, indeed! One wondered how this vision of the family's potential destructiveness fit in with John Miller Chernoff's vision of complex polyrhythms as promoters of social harmony.

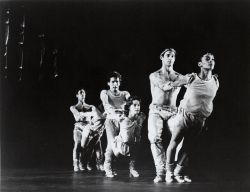

''That seems like a real contradiction,'' Mr. Byrne admitted. ''But I've noticed that even when I write songs about horrible things, the act of performing them with a group of people can be enjoyable.'' Miss Tharp added that ''although there is this idea of the horrible family in the beginning, with various dancers playing the father, the mother, the brother, and so on, by the end of the piece all the dancers have become a community, and rather than portraying characters they've been allowed to become what they are, which is extraordinary dancers.'' Finally, then, Mr. Byrne's music and the ideas behind it shaped Miss Tharp's vision, just as Miss Tharp's ideas contributed to the shape and direction of the music.

''This has been a real collabortion,'' Mr. Byrne emphasized. ''I don't think it would have been as easy with most other musicians; the way I work, recording basic tracks with just a few instruments and then building layers of rhythm and texture of top of that, lent itself to the way we were able to work together. I would send Twyla basic tracks, sometimes just a bass and guitar or a basic rhythm part, within a day or two after I'd recorded it. So she was able to work with tho se tracks while I worked at building up layers and, whenthe music req uired it, writing lyrics and recording vocals. That way the piece dev eloped day by day, both at the dance rehearsals and in the studio.''

Initially, though, the idea for the collaboration was Miss Tharp's. ''It began,'' she explained, ''when we had a West Coast season that was co-produced by (the rock impresario) Bill Graham. At the end of the season, I told him I wanted to do a new piece with some new music and asked him for suggestions, and Talking Heads was one of several groups whose name came up. I went out and got all their records and I found the music to be very danceable, with a lot of physical drive to it, the same kind of physical drive David has as a performer. So I worked with my dancers and some of the old Talking Heads numbers, and then I asked David to come in and look at it and see if it made sense to work with me. Some of that early work I did with existing Talking Heads music and the dancers is still in the piece, if only in the form of basic rhythms.

''So David and I went out, and he offered to produce a demo tape for me, to show me he could do it. I told him I already knew he could do it, and he said 'Fine, I'll start work on it tomorrow.' My agent told me I was crazy, that we should sign a contract first, but we didn't wait for that, we just started right in. That's how things should be done, I think. By the time the lawyers get through, half the time you don't want to do the project anymore.''

This sense of immediacy is reflected in Mr. Byrne's music, which is some of the richest and freshest music he has made. Some of the pieces were written more or less to order, to go with dance movements Miss Tharp had already worked out; other pieces generated dance movements. But one doesn't notice seams showing. Vocal pieces flow effortlessly into instrumental passages, some of which pulsate with crisscrossing rhythms while others have an evanescent delicacy. ''I had done some thinking about music and dance and how they could work together best before I started this,'' Mr. Byrne said, ''and one thing I was sure of was that all the music shouldn't be songs with words. Singing can be distracting in a situation like this; people tend to listen to the lyrics and think they're exactly what the dancing is about. That's why I worked on the basic rhythms first and built from there. Usually, in combinations of music and dance one or the other comes first. But I think a collaboration, with the music and dance developing at the same time, is really ideal.''

Ideal, perhaps, but out of reach for most dance companies. The Twyla Tharp Dance Foundation, which is presenting the company's Broadway run ''with the support and encouragement of Emanuel Azenberg, Bill Graham Presents, and the Shubert Organization,'' is unusually well funded for a modern dance operation. Miss Tharp's Broadway season, her second, will be one of the longest Broadway runs ever attempted by a modern dance company. It is this relatively grand scale that has made ''The Catherine Wheel'' possible. Rock music, especially music that is ''composed in the studio'' like Mr. Byrne's, takes a long time to put together and polish, and time in an adequately modern recording studio costs several hundred dollars per hour.

Ideal, perhaps, but out of reach for most dance companies. The Twyla Tharp Dance Foundation, which is presenting the company's Broadway run ''with the support and encouragement of Emanuel Azenberg, Bill Graham Presents, and the Shubert Organization,'' is unusually well funded for a modern dance operation. Miss Tharp's Broadway season, her second, will be one of the longest Broadway runs ever attempted by a modern dance company. It is this relatively grand scale that has made ''The Catherine Wheel'' possible. Rock music, especially music that is ''composed in the studio'' like Mr. Byrne's, takes a long time to put together and polish, and time in an adequately modern recording studio costs several hundred dollars per hour.

The prohibitive cost of an undertaking like ''The Catherine Wheel'' will probably prevent similar collaborations from becoming standard practice for rock composers and modern dan ce companies. But one suspects that other choreographers will someh ow find ways of financing such projects, and that other rock composers will take themon. The chance to use a modern recording stud io to create a piece of music specifically for a dance presentation i s a chance many rock artists would undoubtedly find challenging an d attractive, and it seems evident that almost any dance company w ould prefer helping to generate a score to working with pre-existing music. ''The Catherine Wheel'' is a first, and one suspects it will not be the last of its kind. It could become the model for a new and much more fruitful interplay between the worlds of popular music and modern dance.