11 THINGS I LEARNED FROM THE HIERONYMUS BOSCH SHOW (I DECIDED TO TRY THIS POST DONE AS A LISTICLE!)

| March 30, 2016

I recently traveled to the small Dutch town of Den Bosch to The Noordbrabants Museum to see the largest assembly of work by Hieronymus Bosch ever assembled, Jheronimus Bosch: Visions of Genius. This town was where Bosch spent his entire life—he lived on one side of the square and worked in his studio on the other. I took a guided tour of the Museum (big thanks to Heidi Vandamme and Tamsin Aarts-Pickard at the museum and to Sander Knol at Xander Uitgevers, my book publisher in Holland!), and afterward I wrote down what I remembered. Needless to say the show is hugely popular—The Guardian called it "one of the most important exhibitions of our time"—and I think it’s fantastic...it’s a window into another world and another time.

1. He was OK with the Church

How does an artist make a living? Bosch’s work was usually commissioned by the Church and displayed there. Historically he was considered to be a critic of the church—there are images of priests behaving badly, lots of psychedelic nightmare imagery, and people have suggested Opus Dei informed some of his imagery—but nowadays it’s commonly accepted that in fact his paintings supported standard church doctrine for the most part. He often painted folding triptychs which, when closed, would show flattering portraits of his sponsors or some other inoffensive images on the outside and, when opened, would reveal the grotesque materials on the inside panels. He was quite a popular painter and at one point EVERY painting was in private hands....for a while anyway (more on this later).

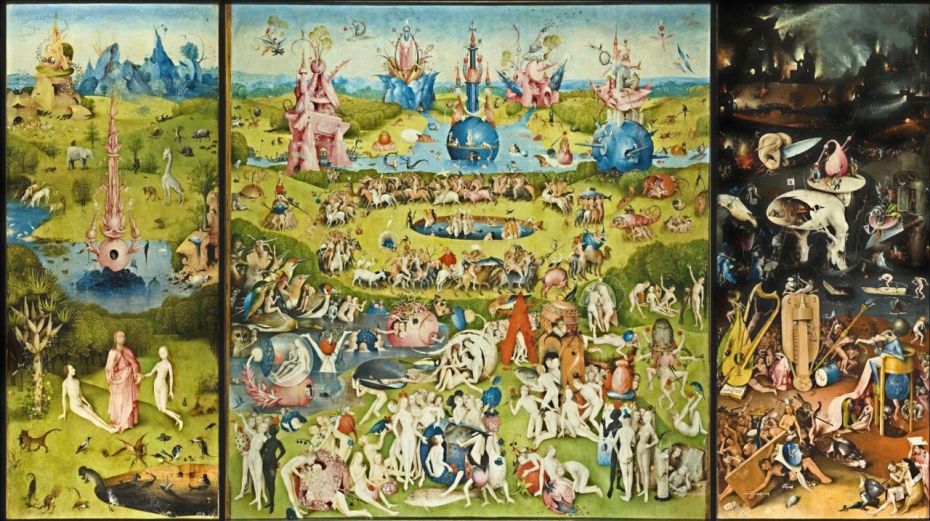

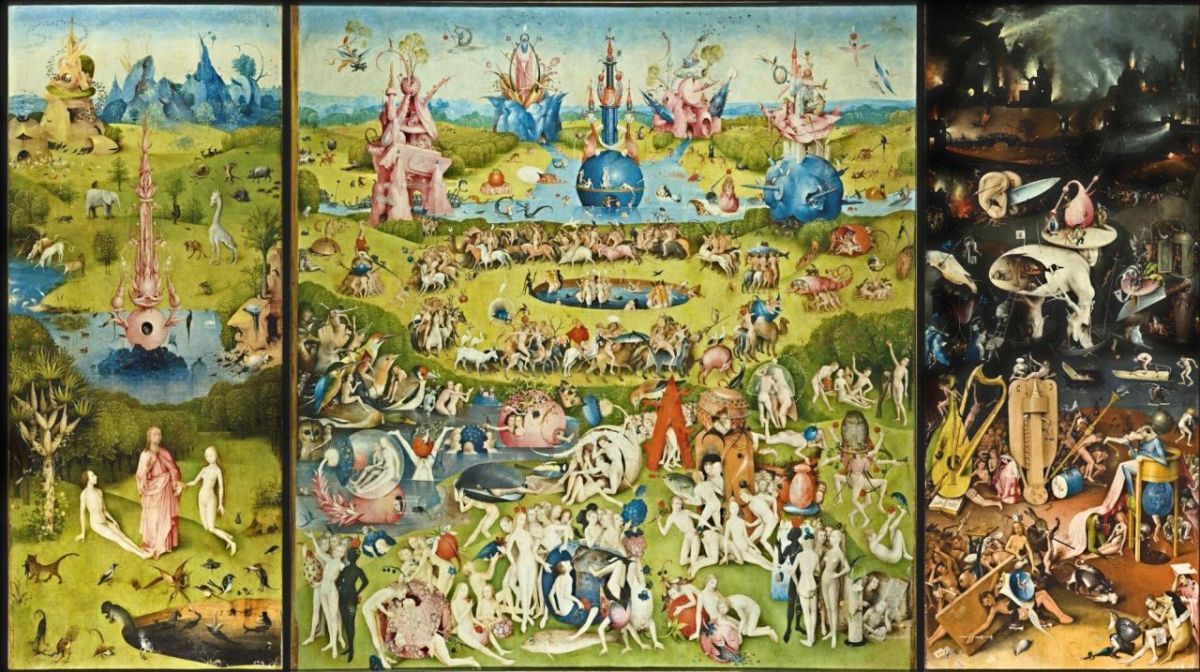

2. Grabbing eyeballs is not a new thing

Sex, fantastic images, and the grotesque were, in a sense, marketing tools Bosch used to draw an audience to his work. These details encouraged his viewers to really look closely at the work, which often carried a deeper moral lesson—stay clear of music and dancing, don't hoard your money, you're all going straight to hell and you don't know it, for example. My people’s instrument, the bagpipes, are portrayed as an especially odious musical instrument. FYI: "doodlesack" is how you say it in Dutch and German!

3. Symbols change their meanings

The owls that pop up in many of Bosch’s paintings symbolize the devil’s influence, not wisdom as we commonly attribute to them today. Symbolism, it seems, changes over time—what an image meant to folks during Bosch’s days might be different than the way it’s interpreted now. One can’t assume allegorical pictures like these can be read according to our contemporary set of associations. I suspect Bosch lived the freak show as much as we do today, but what they took away from it was quite different. The owls in the paradise of, for example, are reminders that the devil's temptations are hiding everywhere. Here is one lurking in paradise, an ominous portent of what’s to come:

4. Make more of what sells

We sometimes think of artists in romantic terms, as being above the fray of business, but in Bosch’s day artists were often entrepreneurs as well as creators. Like the work of many others artists of the time, if a picture was popular many "followers" made and sold copies. These followers were often artisans in Bosch’s own studio. As such, attribution of Bosch is difficult and his work has been confused with employees of his studio or pupils of artists who worked in the same atelier. In fact, one painting in the show was recently discovered to be a copy and another drawing previously deemed to be a pastiche is now thought to be original.

After hearing this I wondered if sometimes a copy might improve upon an original, in conciseness of ideas or technique? Perhaps this is the path of innovation in general? In art, at least, we tend to ascribe the highest value to the original—or, in other words, the "invention". But in other areas—tech comes first to mind—innovation on an existing invention is more valued. As Bill Walker wrote in his article "Innovation vs. Invention: Make The Leap and Reap the Rewards" for Wired magazine:

Was the iPhone a great invention? We can dissect the iPhone into individual inventions and evolutionary consolidations of other gadget functions and features. There are really no ground-breaking inventions from a technical perspective, in the first (or second, or third) generation iPhones. … Was the iPhone a great innovation? Absolutely. The iPhone created an ecosystem of media content, telecommunications, licensing, application development, and unified them all under one roof.

Regardless, it does seem that unlike a lot of the tech world, Bosch was both inventive and quite successful. I imagine that inventors and early innovators would be curious how he did this, as it seems quite rare today—I don’t have an answer.

Bosch was considered among the first to paint things that were wholly out of his imagination. Previously there were standard demons as described in the Bible and elsewhere, but his figures went beyond that. His landscapes were fictional, too—a conflation of traditional Dutch elements and imagined versions of somewhat spectacular Middle Eastern holy lands. While Bosch did not travel, the crusades, trade, and travellers brought images from afar (of Middle Eastern dress, exotic animals, etc.) that he incorporated into his paintings. Here’s a giraffe—he’d never seen one!

6. The paintings use narration as a means of instruction

Almost all paintings of the time used visual tropes to impart a narrative, due to the fact that most of the general population was illiterate. Books were not yet made available to the public and sermons were in Latin so visual storytelling and instruction was key—the spiritual and moral message being: all are blinded by the pleasures of the haywain, we are all blindly following the herd and, if you don't pay attention, horrible penance awaits! In a sense Bosch could be said to prefigure the individualism of Luther—don't follow the herd!

7. Humanity is, for the most part, wretched

There are many crowds in Bosch’s works and, with the exception of his patrons who were depicted as monks or other good guys, all are very human and cartoonishly grotesque—lovely, really! In the room featuring his drawings, you can really see the resemblance to Disney’s characters and other cartoon and comic art—in part because they are all line drawings. And there’s humor here, too, with drawings of people fucking and pissing. Bosch seemed to be better at depicting this gloriously eccentric humanity than most—even his studio artisans didn’t seem to quite capture that living, breathing humanity.

8. The market made the state

There's still a giant street market here (one street smells like cheese!) and in Bosch’s day the town was famous for its fabrics (solids in particular, red was a big color), shoes, and cutlery. One might assume that Bosch was proud of these locally-made artisanal products, as his paintings feature examples of the knives and such—so it seems product placement isn’t a totally new thing (though these images were probably included due to local pride rather than in an attempt to garner sales). Once the market was established, the successful merchants wanted to protect it, themselves, and trade in general, so the sales were taxed and a sort of state equivalent was established to provide protection, justice, and services. (One can assume, then, that the royalty—which, along with the church, constituted the state equivalent—weren’t providing all these services.) Aided by that structure, the town did well, and so did the local church, St. John’s Cathedral. Bosch was a member of the influential religious group, The Brotherhood of Our Blessed Lady, which commissioned works by himself and some other well known folks.

9. History determines provenance

The paintings were produced for the Catholic church, but the Reformation was just around the corner and would erupt into an 80-year war with Spain. The town of Den Bosch was fought over, changed hands a number of times, and ended up being ruled by Philip II of Spain—hence the large collection of Bosch’s work that ended up at the Museo del Prado in Madrid.

10. Restoration equals re-creation

In one of the explained restoration efforts, a female saint had her beard painted back on. Restoration goes way beyond wiping off accumulated dirt—and sometimes it even includes the creative act of female beard painting! Modern technology allows us to see what has been covered up in order to restore the creator’s original vision.

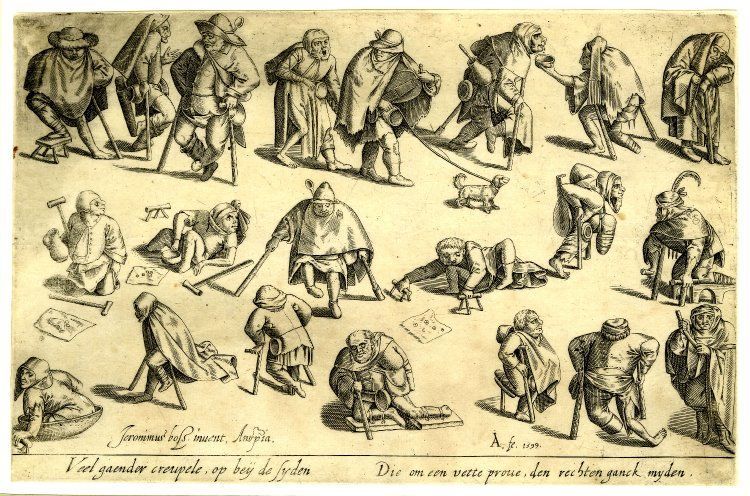

11. Bosch was a dark comic artist

As befitting the narrative nature of his work, the preparatory sketches will strike a chord with anyone who’s familiar with graphic novels and comic art—R. Crumb, S. Clay Wilson and others come to mind. There are pages full of exaggerated drawings of beggars, monsters and freaks...which would make some nice wallpaper!

So, why might you be interested in this?

It’s a visit to an alternative reality—a view into not just Bosch’s images, which are plenty for sure, but also into the greater context of values and situations that surround and affect the work. Those forces and how they function have changed over time but the process, I suspect, is the same. There’s an inherent pleasure in escaping one’s own world, too—as any video game addict will tell you! Whether through images, stories, music, performance, sex, ritual, or drugs, being in another world is both enjoyable and informative, as we see our own worlds differently when we return.

Jheronimus Bosch: Visions of Genius is at The Noordbrabants Museum. It closes on May 6th, 2016, and is unlikely to be mounted again in our lifetimes. Tickets are timed and sold in advance on the museum’s website. The town of Den Bosch is very nice and the museum is just a 12-minute walk from train stop.

DB

Den Bosch / New York City