ENGINEERING AT THE ROYAL BALL

| May 12, 2014

I was invited to the Met Ball by a friend. It’s quite the anthropological experience. This year the exhibit was the work of Charles James, a UK-born, US-based designer and, yes, artist, who did extraordinary work in the '30s, '40s and '50s. In keeping with that era, we men were expected to dress in formal attire that might evoke Fred Astaire. With a lot of help from the folks at Rag & Bone, I sported the appropriate attire (tails!), but didn’t quite approach the level of glamour and suave sophistication that might have been hoped for. Regardless, it was a fun opportunity to play dress up.

Women were expected to do likewise, and there were many, many dresses with trains at the royal ball. One had to be careful where one stepped, as a dress could extend many feet behind its wearer. I saw one elegant woman whose dress was torn before she even made it inside.

I’ll skip the red carpet stuff—the web is probably full of that. I was introduced to people I didn’t know—and some I did. I shook a lot of hands and tried to introduce myself and pronounce my name clearly.

The show itself is pretty extraordinary. I somehow suspect that the web is not going to focus on the show, so here goes. James’ early work features innovative wrapping—one dress is made of two panels sewn together that are pie-shaped parts of a circle, but are wrapped between the wearer’s legs! One outfit called the “taxi dress” was designed so it could be changed into or out of in a taxi—for quick sex or for rushing from work to an evening out?

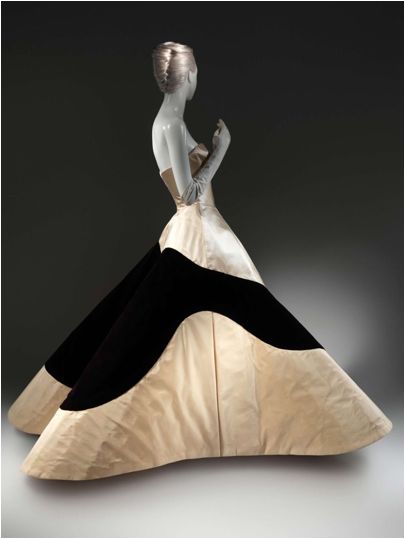

The work he’s best known for are ball gowns made for super rich ladies—wives of oil magnates and such. These tend to be elaborate constructions that almost stand by themselves. This one can barely fit through a door.

The pieces are often made of very expensive materials, cut in innovative ways and draped over armatures made of ivory, muslin and metal. (These dresses were heavy!) Here’s one that looks almost Victorian:

The installation, by Diller Scofidio + Renfro was very cool and turned what could have been a boring (for me) exhibition of ball gowns into a show of cleverly engineered sculptures.

In the installation there were, in most cases, computer-generated videos that showed, via animation, how the armatures were shaped and attached and how the weirdly folded panels of silk and other fabrics were draped over them. Often these were like looking at X-ray views of the objects in front of you. You could suddenly and easily understand what was holding them up and how they worked—sort of.

In other spots the high-tech deconstruction went even further: moving robot arms held both lights and cameras that played across the surface of the items; the computer animations showed what was going on beneath the surface while the moving cameras projected close-ups of the folds and fabric on big nearby screens.

Here is what one of the close-up robot cams was projecting:

The objects, most of them more that 60 years old, were being revealed via the latest technology—in a kind of symbiotic relationship that made me look and appreciate these things in a completely new way. That’s not to say one can’t just look at them—they’re plenty bizarre as they are. Here’s a dress with inverted breasts. It looks like a sea cucumber.

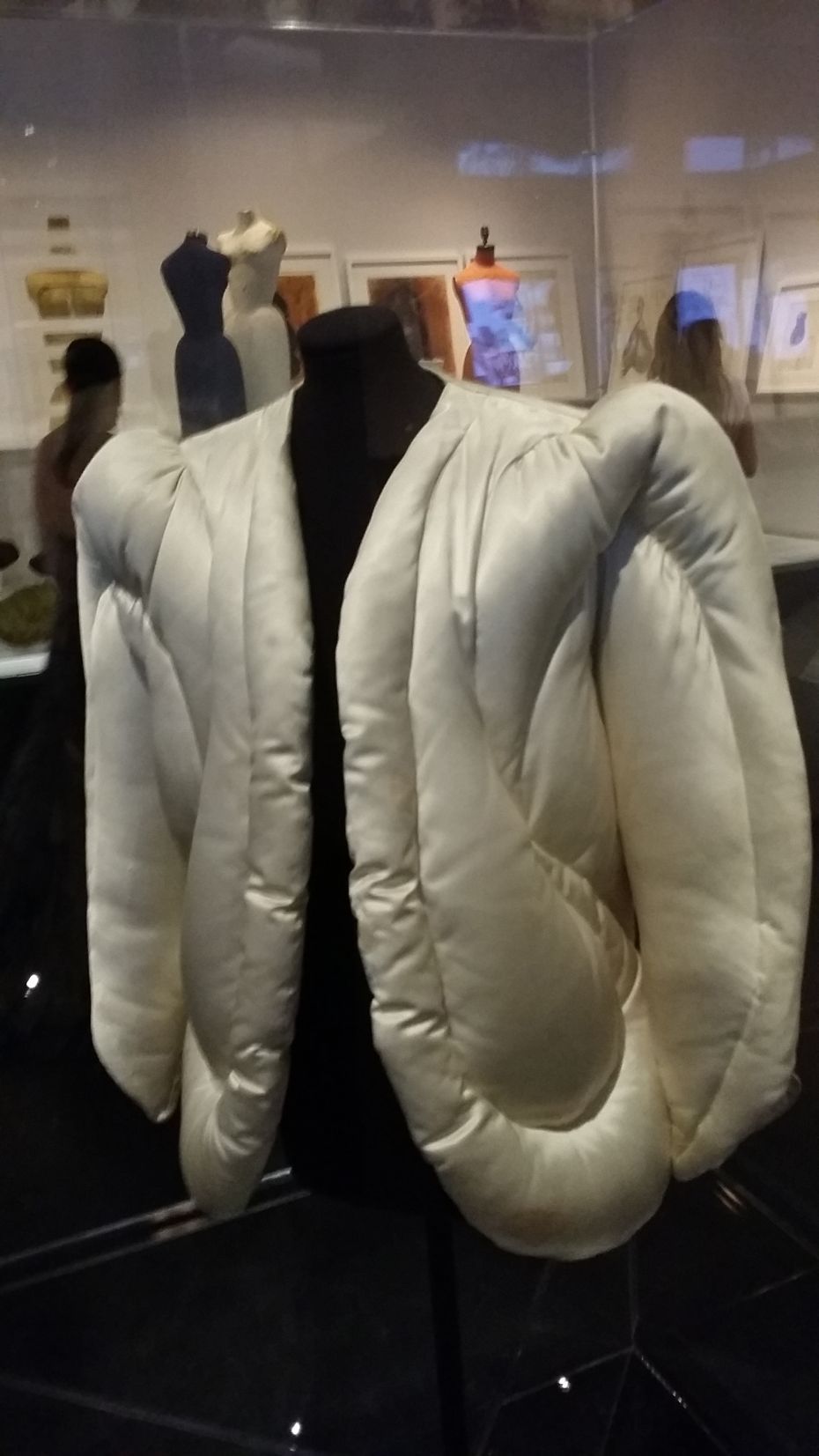

Downstairs the exhibition continued, though almost no one was there (to get downstairs, one had to traverse almost the whole museum)…but it was worth it. Here’s James’ famous puffy coat that he did way way before anyone else:

James was notoriously temperamental and fussy. One could say he was an artist who wanted his work seen in the best way possible, but after insulting too many rich lady clients and their friends (he called one woman a frump to her face and refused to dress her), well, the commissions began to dry up. Times were changing too: in the '60s, even those ladies weren’t wearing hugely expensive gowns (one of the special pieces would cost around $1,250 in 1950 dollars—that would be about $12,000 today.

James died penniless in squalor in the Chelsea Hotel in 1978. Changing times yes, but a lot of his problems he seemed to have brought on himself. The artist as a horrible, bad-tempered asshole—we all know them. Some of them manage to establish a situation where folks tolerate them and excuse them, but even those (hello, Galliano) will be avoided eventually.

James made a list of those he hoped to dress someday: Bowie (no surprise) and Lou Reed (talk about combustible!). He married and had children (!) and believing that outstretched, forward-reaching arms were a desired posture for a child, he made his a lovely outfit in which no other posture was possible. The poor thing couldn’t ever let his or her arms simply relax and hang.

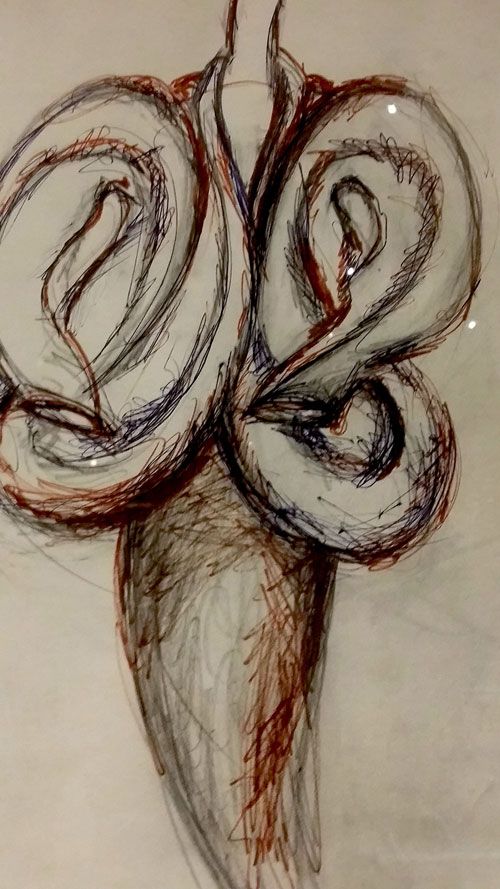

There were some drawings too—hairy creatures (I assume it’s some sort of radical spiky fabric) and a coat even more convoluted than the puffy one he made, see sketches in gallery below:

My guess is that without James we never would have had Rei Kawakubo, Issey Miyake and all that innovative clothing (mainly Japanese) from the '80s. Lots of stage and pop star costumes were no doubt influenced by James, as well. Nice to see him celebrated as the structural engineer he was.

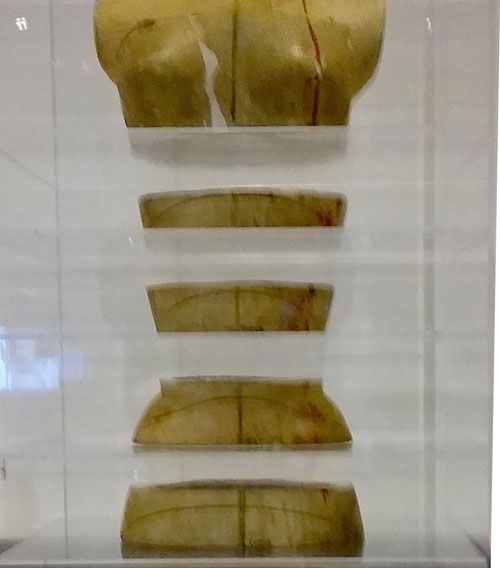

Here is a sliced up dress form:

But back to the ball. I said hi to a couple of singers I knew (Florence Welch and Janelle Monae) and enjoyed the variation on chicken pot pie served at dinner. Frank Ocean sang two songs with a full orchestra: “Super Rich Kids” and “Wiseman.” He sang beautifully and the arrangements worked well in his songs—but only two songs? The orchestra was all women—in top hats. Rachel Drehmann, who played french horn with St. Vincent and I, was there, too.

I was home before midnight…just in case the spell wore off.