Cultural Spaces: Inhotim

| April 6, 2018

Friday the 30th of March, a group of us travelled from Belo Horizonte to an arts project in the countryside called Inhotim. Instituto Inhotim is a private “museum” and botanical garden about sixty kilometers from Belo Horizonte in Brazil. Above is the view from the park/museum.

It was started by the mine owner and art collector Bernardo Paz as a space where he could show his collection. Then Brazilian artist Tunga suggested to him that he expand the idea by adding contemporary art, which he did, but more in the form of permanent installations than what one would encounter in a conventional museum. Therefore it feels a little more generous than the usual display of baubles amassed by a wealthy collector. Not that he’s totally a good guy—Paz was recently convicted of money laundering and sentenced to nine years in prison, but his project lives on.

(That looks like another mine in the distance.)

The park is on the site of Paz’s former mine, which was all replanted as per government regulation. It's massive—larger than the Venice Biennale's Giardini and the Arsenale exhibition spaces combined. When we arrived we saw a giant parking lot, which by the time we left, was filled with tour buses and loads of cars that brought Brazilian tourists, of all sorts and from all over the country, to the museum.

From what I observed, the general public who aren’t familiar with the work of the artists included here aren’t intimidated and don't feel they don’t get it because they lack some art education. It's all very open and accessible. The artists have made adjustments too. They have made new works or have chosen pieces that work well in this context.

Visitors often spend more than one day here—as they would at the Biennale—and like the Biennale, Inhotim consists of lots and lots of separate pavilions. Pictured below is the corner of the pavilion for the Brazilian artist Adriana Varejão, who was the first artist to have her own structure.

Adriana came to our Rio de Janeiro show, and I had met her years ago. She helped connect us with two young curators. Her work often uses tiles; in this case, some have local birds on them, others feature images of psychoactive plants and others depict gruesome guts. But check out the approach—with the blue-colored pool against the lush greenery and the concrete pavilion:

There is an integration between the surroundings, the park, the landscaping (Roberto Burle Marx was an advisor), the buildings and the installations. There are cafés, lakes and paths through the jungle, and golf carts you can use to get around if you're in a hurry. Fallen trees—often Brazilian hardwoods—are turned into pieces of furniture. All of them are different, sprinkled along the paths.

Since Adriana’s pavilion was built, a number of other artists have been given their own buildings and shows where their work is on permanent display—often in the form of installations, rather than paintings or a similar type of work hanging on a wall. Many of the artists’ works were tailored for these structures, and in various cases the pavilions themselves were bespoke—made in collaboration with and specifically for each artist. This makes each space seem more experiential, and that might be part of the appeal to a large and wide variety of people. The members of our tour group were unfamiliar with most of the artists—but they still loved the park and the experiences. You don’t need to be an elitist art snob to “get” this place.

Of the artists represented, about half are Brazilian or Latin American, and half are “international” from other parts of the world. Here is Doug Aitken’s pavilion:

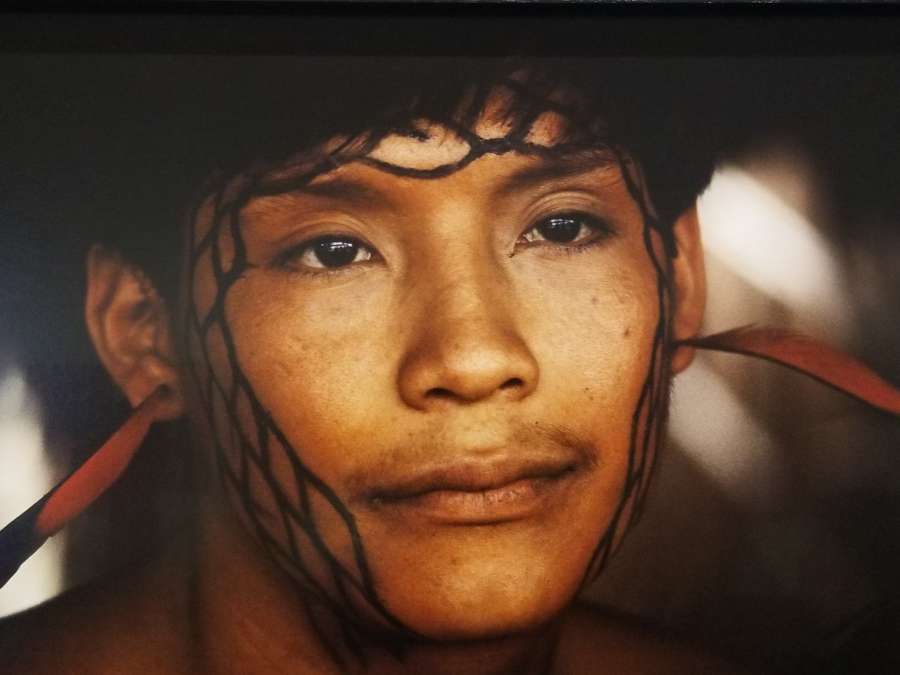

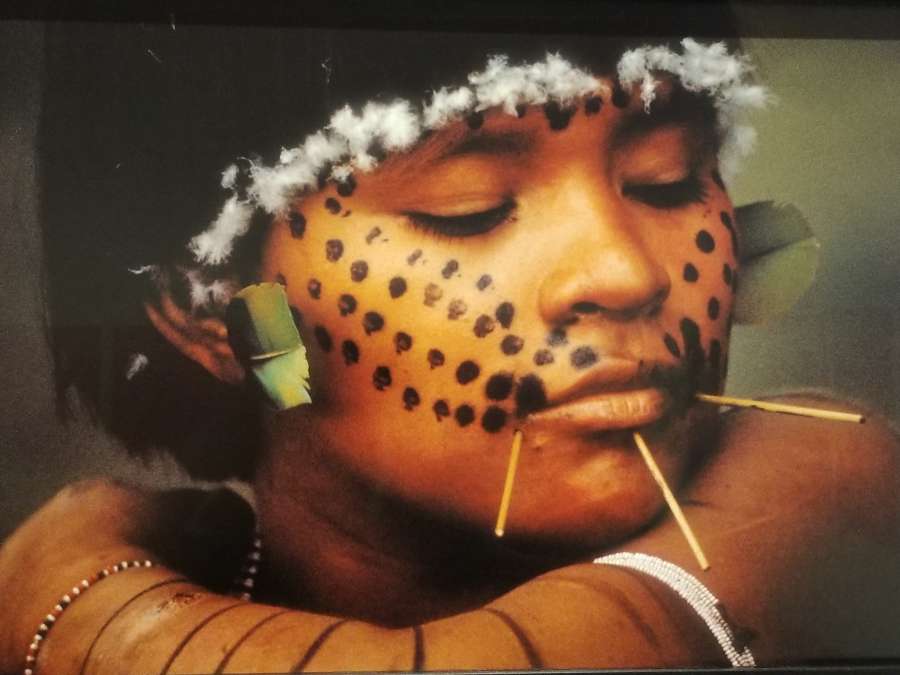

In the center of the room is a hole that was drilled 200 meters into the earth and emits sounds—rumbles and roars—that build and subside. Inhotim also includes work by Olafur Eliasson, Tunga, Cildo Meireles, Lygia Pape, Janet Cardiff, Doris Salcedo, Claudia Andujar (a photojournalist who lived with the Yanomami), Yayoi Kusama, William Kentridge and other Brazilian artists I wasn't familiar with.

Here are a couple of Andujar’s photographs of the Yanomami—they were obviously very comfortable with her:

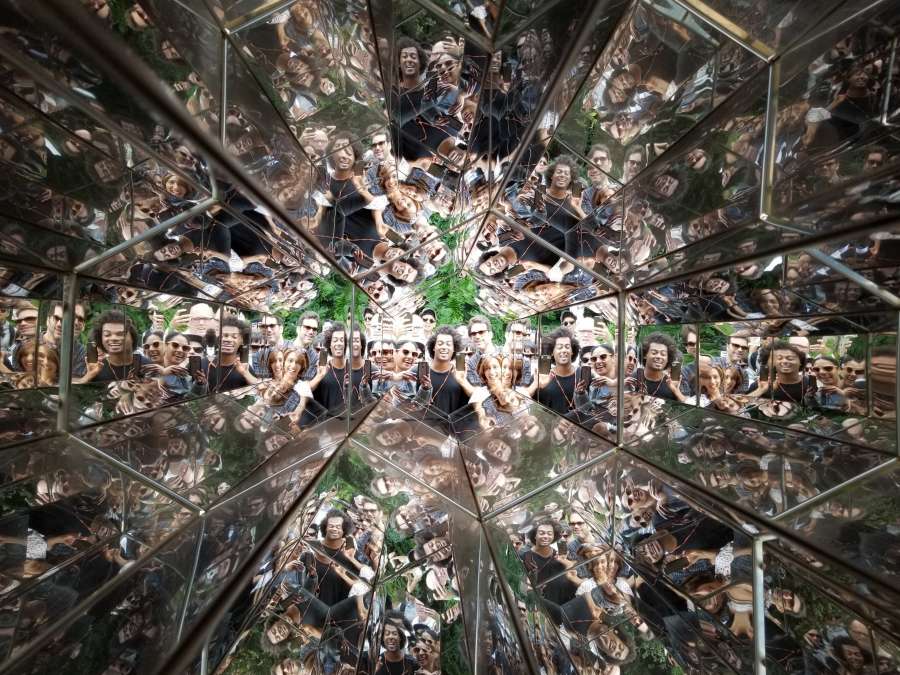

And here’s an image of some of the band reflected in the Eliasson piece—a very large mirrored tube that's basically a simple kaleidoscope on a swivel base:

He had another piece here too—a small dome with a fountain in it. When you go inside, it goes dark, and a strobe light goes on, making the fountain water seem to freeze.

These are both well-known effects that we have all seen—at least I have—but that everyone loves anyway. It’s pure entertainment. It says it’s OK to simply play and enjoy.

So, if Inhotim works—and it seems to—why does it and what’s the deal?

Maybe it’s the trip through little, rural villages through the outback that is part of the fun. A voyage to a destination builds anticipation.

Maybe it’s the experiential nature of much of the work. Maybe it’s the integration of park, jungle and birds… You relax and let your guard down—as one does when immersed in nature. It works better than the usual rich collector’s personal museum, of which more are sprouting up every day—gotta park that money! Which is maybe how this one started, but it has morphed into something else entirely.

What’s the deal?

With the founder presently in jail, the government has stepped in and taken over the museum’s costs and upkeep. I wonder who makes the aesthetic decisions now? Is the project frozen? The annual maintenance costs run about $10 million. There are more than 200,000 visitors a year which is healthy given the remote location. The entry fee is 44 reals (about $13 USD). The landscaping alone must involve heavy upkeep—tropical growth takes over quickly and in the heat and humidity here, things fall apart as well. Yet everyone who comes seems to love it; as far as I’ve heard there hasn’t been a protest.

So, here’s an art institution that is primarily experiential and that doesn’t change—there aren’t rotating shows. Unlike many collections the work can’t be moved or travel. You have to come to it.