Museums for All of Us

| July 23, 2018

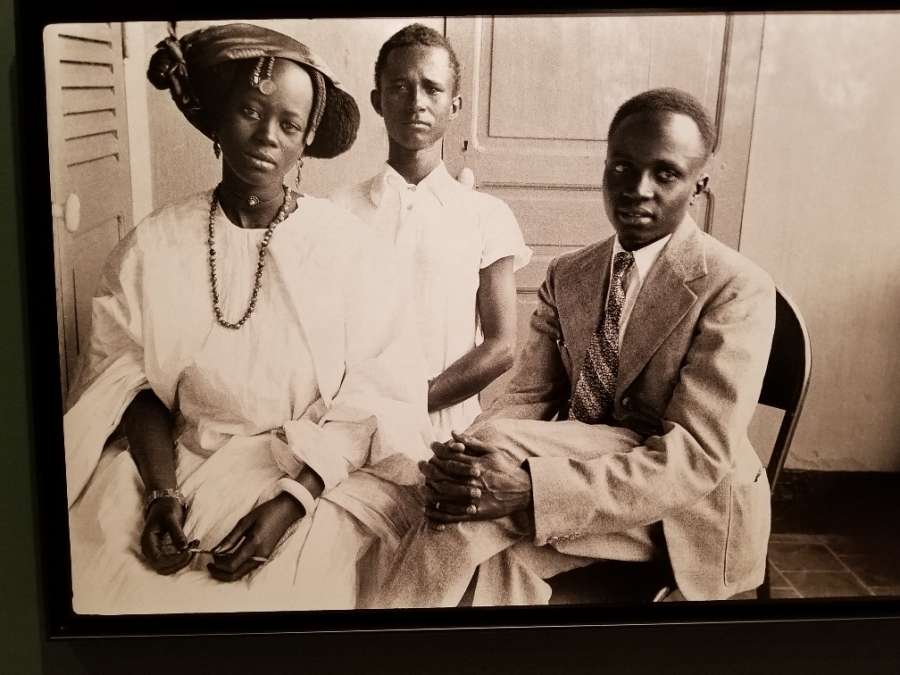

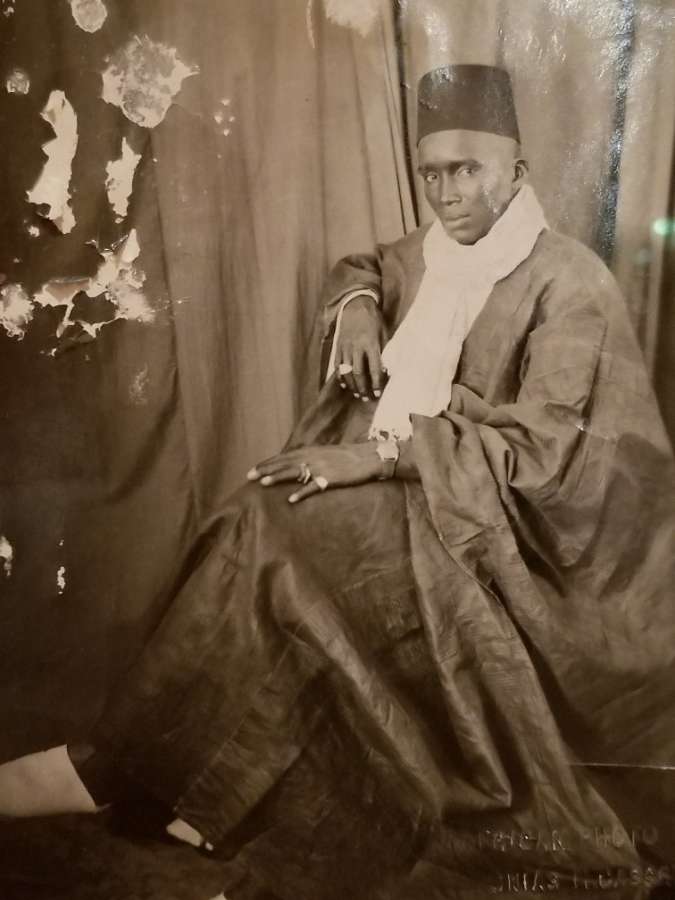

This month, Photo España Expo is on—it’s a kind of photo biennale that takes place in venues all over the central city. I first went to see a show of early 20th century African photographs. These are absolutely lovely and, as the wall text says, in these images we see people taking control of how they want to be presented… not as “other” or exotic or primitive. In these photos, these folks look like people I might know. It’s very moving

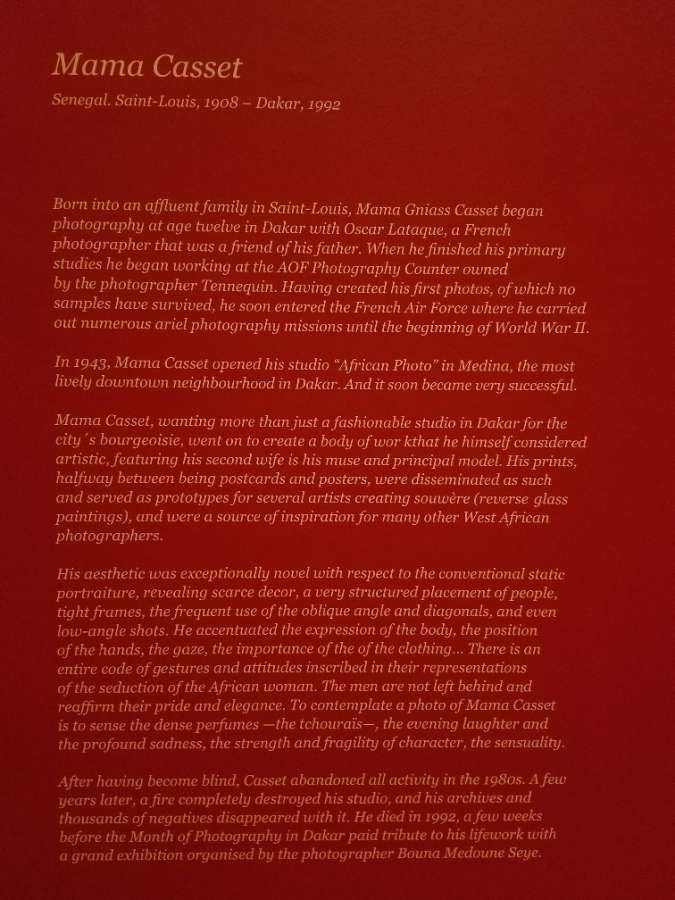

The wall text reads:

The Elephant Senegal

Elegant and distinguished, modern and prosperous: this is how the African men and women posed before the camera during the late 19th and early 20th centuries in the great African coastal cities and in Senegal. This is how they presented themselves and this is how they wanted to be represented for all to see. Their photographer, also African, knew how to portray his fellow people, which was quite different from the exoticism that European photographers looked for. It was a Europe that was convinced that the Other should justly remain as the Other, a savage. They were, above all, in no regards one of them, different merely because of the color of their skin.

Here is the affirmation of an Africa without any inhibition in revealing a new image of themselves, which is entirely consistent with the times, and proves to be capable of rejecting and distinctions from the rest of humanity attributed to them.

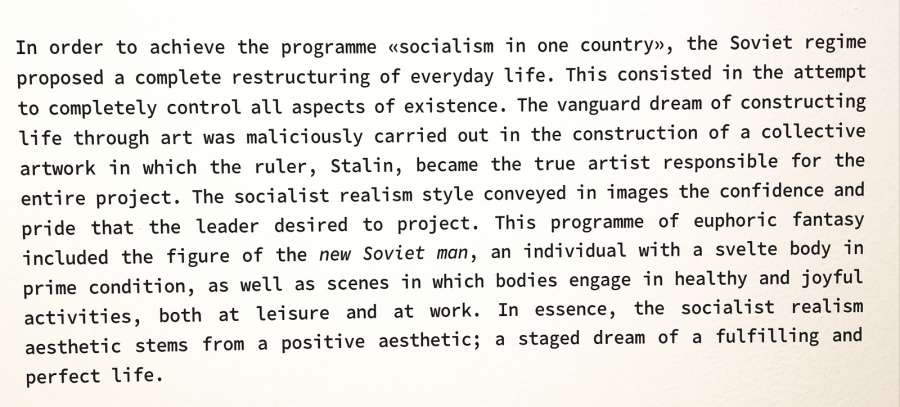

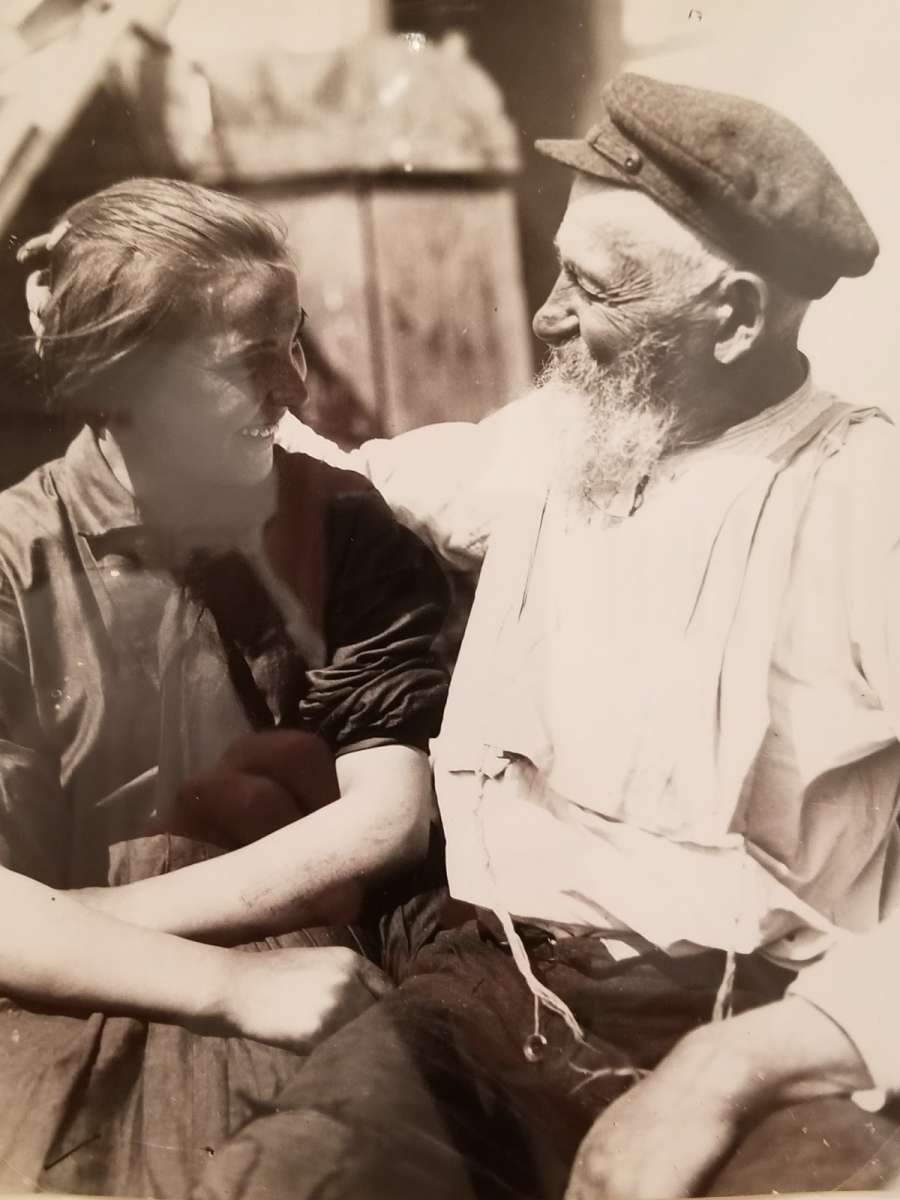

Then, after absorbing some of that I went to a massive show of Soviet photography across the street, which gave me much to think about. The Soviet project truly was a religion, but one whose rules were subject to change (especially once Stalin took over). Pre-Stalin and after the revolution, it seemed to many to be a period filled with hope and promise, a period filled with endless possibility and the idea that the world could be made anew along fair and rational lines.

Every aspect of one’s life was up for revision—no detail was too small if one’s project was to reinvent civilization and society. Here’s one of the wall texts:

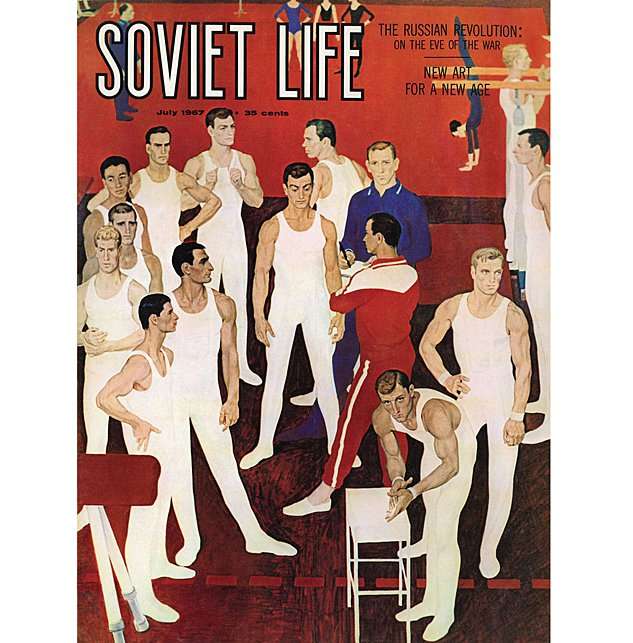

Gymnasts of the Soviet Union by Dimitry Dimitrievich Zhilinksy (1964).

Before Stalin decided otherwise, the cultures of the central Asian areas were respected, maintained and even elevated. As seen in early journalistic photos, these areas were more or less medieval before the Soviets decided that everything had to change… life in Central Asia had remained the same for eons. Surprisingly to me, the early Soviets defended and encouraged all these diverse cultures.

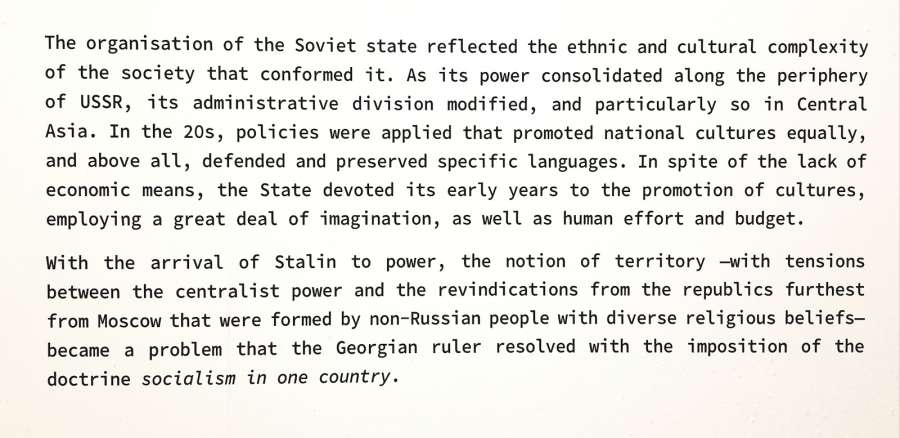

At this exhibit, there were a series of journalistic photos like the one above that soon enough segued into propaganda. Here is a picture that shows a young Kazakh woman trying to convince an old Jewish man not to wear his religious garb anymore (they did the same with Uzbeks and the veil).

Here is an early picture of “Women’s Day” in Tashkent.

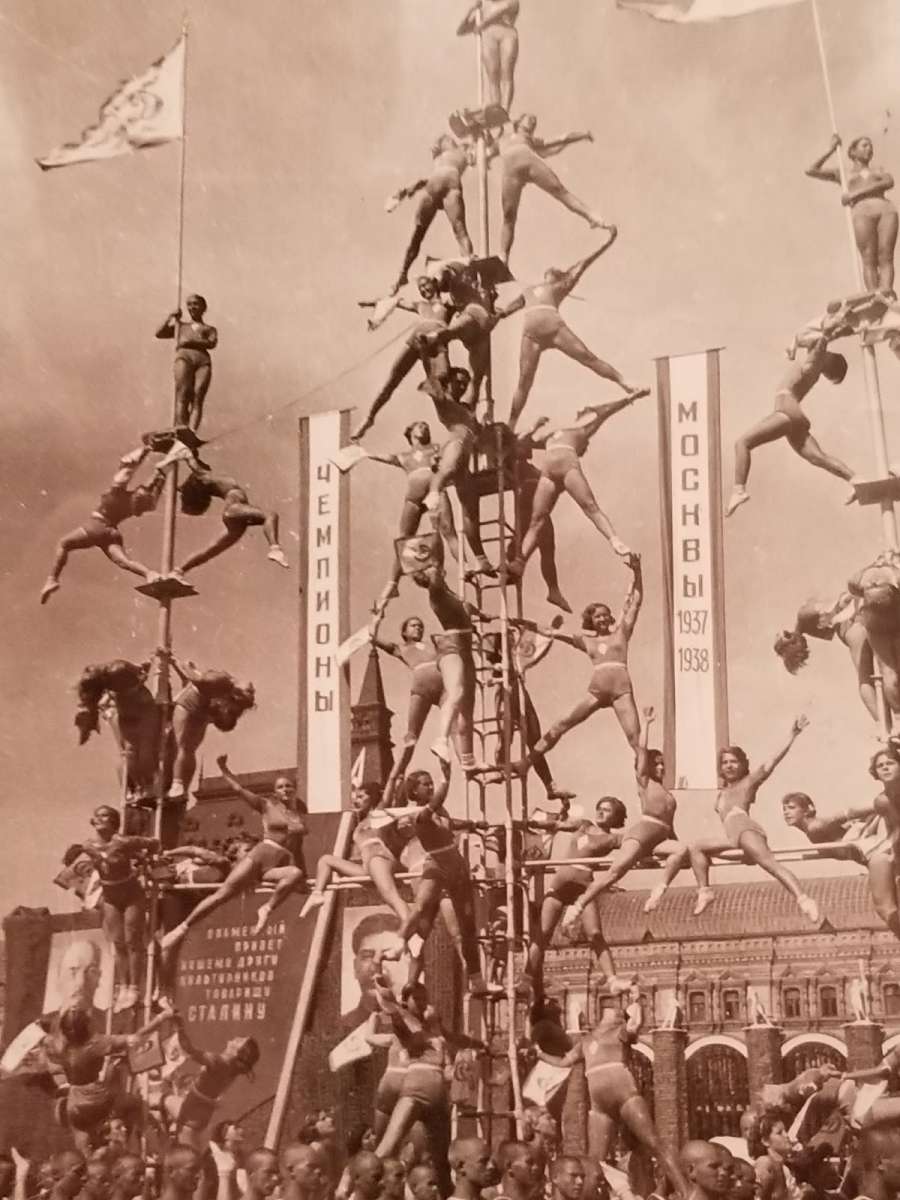

Conceptually it’s easy to see how the Soviet idea was so enticing at first. The chance to make the world anew was an idea so seductive that many put up with the hardships that followed when everything didn’t go smoothly... you’ve got to break a few eggs to make an omelette. Sadly that ended up being millions of “eggs”. The pictorial propaganda effort soon intensified in case anyone had doubts, apostates were suppressed, folks supported and sacrificed themselves for the war effort. The image of healthy “play” fit the idea of a new kind of society. Keep the faith. It will be worth it. We’re making a completely new society. The whole world will be a better place. We just have to deal with a few “problems”.

There’s Uncle Joe watching over the women gymnasts (this was 1937-38… different times coming soon!).

The Prado: White Men and Naked Women

Then I went to the Prado. It’s giant. It’s overwhelming. I love the surreal storytelling that is the content of so many of the religious paintings there—apparitions, visions, miracles, witches! Bosch! Zurbarán, Goya. The world as seen in these paintings is a place full of magical possibility.

The Apparition of Saint Peter to Saint Peter Nolasco by Francisco de Zurbarán.

Very very cinematic many of these religious paintings, and there are lots of them, and they are big!

Originality is something we often value highly in artwork, but here and there some doubts creep in. One of the black Goya paintings—a giant terrorizing a village—is no longer attributed to Goya it seems. It was at least someone he often worked with.

Here’s a Rubens and the painting it is copied from. Ruben’s Adam is not quite as buff, but his Eve is exactly, exactly the same… just a little paler.

Adam and Eve by Pieter Paul Rubens (copy after Titian).

Daniel Dennett as God (who knew?), the dove with lights steaming from it’s underside, the holy spirit and a buff but demure Jesus with some wispy decor draped over the cross.

El Salvador by Antonio María Esquivel.

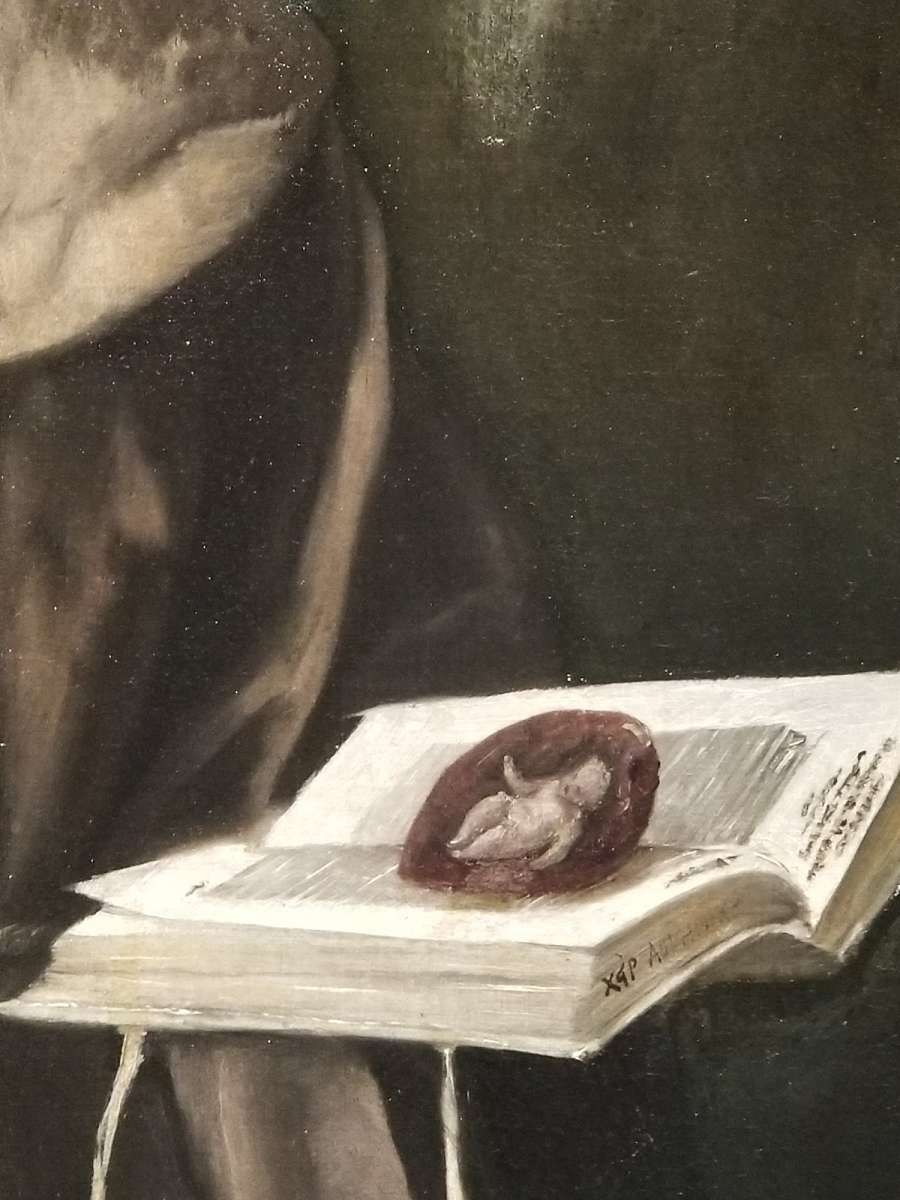

Here’s a detail in which a little baby Jesus pops right out of the pages of a book. Like I said, very cool, iconic ideas here that one would not be surprised to see show up in a fantasy or sci-fi movie. I enjoy this stuff, very exciting.

Overall, after having been barraged by these images, I was struck by the work being in aggregate mostly a parade of eminent, well-dressed white men and some naked women. That's what it is, objectively. The glorious history of European art.

I've been hanging out and riding the bus with the band as we tour around, and we’re a diverse bunch, so inherently I wonder, "What would it be like for some of them to wander through here?" Some would surely wonder, "Where is anyone who looks like me?", and then that might be followed by, "Why should I care about these people?"

I can’t claim to know what it’s like to be black, or Asian or anything other than what I am, but I know what it’s like to be somewhere and to look around and to say to myself, “There’s nobody else here like me.” Luckily, for many of us, we discover from an early age that music and the arts can be places where we all belong, where we’re welcome.

That’s not to say we can’t enjoy and immerse ourselves in worlds and cultures different than our own, but often the opportunity to do so for the people like me is OUR choice. Big difference.

So I think to myself that as the makeup of the first world changes, and it already has, museums that implicitly present themselves by saying, "This is our culture, this is who we are," will have an obligation to reflect what that culture is now. The definition is not static. Not every museum has defining culture as their mandate. Not every museum is trying to tell the national story, but for those that do, these are interesting times.

This is from Wanda Nanibush, who is Anishinaabe and a curator of Native American art in Ontario in a recent NY Times article:

“She said that her efforts [to include more Native American art in the museums] were not just directed at museums and artists, but at everyone. ‘Museums are the cultural keepers,’ Ms. Nanibush said. ‘We come to them to learn our stories, and find out what our humanity is.’”

The world has changed. These cultural institutions need to be for all of us.

DB

Madrid