NO MORE RECORDS

| December 3, 2013

These days, it’s common to hear talk of the demise of recorded music as a source of income for musicians and the concurrent re-emergence of live performance as the primary way that we will hear and experience music (and by which musicians will make a living). It seems this is not a new idea.

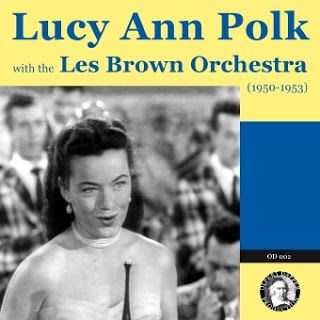

I recently received a CD of recordings by Lucy Ann Polk singing with the Les Brown Orchestra. These live recordings were done in a radio studio and were made to be broadcast to US marines in the early 50s.

The un-credited liner notes tell a surprising story.

It seems that before 1940, most big bands got hired by radio stations to play live for each station’s broadcasts. There was a giant recording studio upstairs at Radio City Music Hall (note the name) where large bands and orchestras would play live and their sets would be broadcast around the NY area. This was a lucrative and continuing source of income for bands that had many mouths to feed (Les Brown’s band on these recordings had 18 members). A band could tour and play for radio stations in many cities, as each station’s broadcast only covered a specific region. With the improvement of recording technology, the growing power of the record companies and records replacing live performances, this way of life was perceived to be threatened. The radio stations were considering playing exclusively records instead of hiring live bands. Income from recordings at that time, for the musicians, was close to zero—so a fight was immanent.

James Petrillo, the new leader of the American Federation of Musicians (the musicians’ union), decided this was a battle that had to be won. He demanded, on behalf of musicians, serious compensation from the big record companies; he wanted them to pay royalties on recordings, which they didn’t do before that! The labels didn’t agree, and getting nowhere, Petrillo called for a strike. A musicians’ strike! Before the strike began, the labels hastily arranged to make recordings of all the biggest bands, to stockpile them. But even those eventually ran out. The strike began in 1942 and lasted for two years, when the record companies eventually caved in. During the strike, bands could still perform live, and play live on the radio, but no union musician in the US could record. Even President Roosevelt got involved, writing a letter to Petrillo to try to resolve the strike…but the union held firm, and now we get some royalties from recordings.

Technology may be disruptive, and the owners of that technology may lack scruples, but it is possible to get a fair deal…with some pressure and by pulling efforts together.

Significantly, singers were exempt from this strike, and could record with minimal accompaniment, backed by a piano or harmony singers. Though the strike was successful, there were unintended consequences for both these singers and the big bands. The public, who used to hear the big bands regularly—bands with rotating singers for hire—got used to hearing more singers and began to gravitate to them by name. The bands (there were hundreds of these large groups) began to fall out of favor. The post-strike recordings now had the vocalist getting the main credit with the orchestra or band listed under them. One record company re-issued an old Sinatra recording and put his name above the band, whereas previously it was in tiny type at the bottom. The record sold incredibly well. That’s the way it has been ever since: the singer gets more credit that anyone else...and the public knows vocalists, but rarely who played on their sessions.

By the end of the 40s, most of the big bands had gone out of business except for the most famous ones—Les Brown among them. Doris Day was an early singer with his band, and Lucy Ann Polk took over after her. Here you can see the Brown band in their trademark plaid suits backing Ms. Polk:

The rise of bebop was also undocumented because of the strike. The early bebop experiments happened during the strike, and no one recorded them.

So now, for better of worse, we singers get top billing. “The cunt in the front,” as some musicians refer to us. Bands from then on got much smaller (jazz combos, rock and roll) and singers would get signed to labels without their band, as Frank Sinatra eventually did. It is the singers and writers who get the lion’s share of recording royalties now, with some of it divided up among band members, in some cases—though often the musicians who play get paid for the session and that’s the end of it. Having just spent a LOT of money on musicians for the recordings Annie Clark and I did for our record a couple of years ago, I’m not sure I’d be willing to pass on some of our royalties in addition to that—royalties that increasingly dwindle as record sales drop. Were I to offer the players a cut of the profits, they’d probably opt for the flat payment upfront if they did any research.

It would seem the new recording technology combined with the greed of the record labels (in not offering royalties) had profound and long-term effects. Some of us would say the establishing of royalties was a good thing, but the loss of employment for so many musicians wasn’t so great. Could the same thing happen today? Could musicians or other creative folks strike in order to get a fairer deal from the digital and media companies that are making loads of money from the content created by them? It doesn’t seem conceivable now, but back then, folks didn’t believe Petrillo would actually pull it off either.