This Business of Show

| June 15, 2017

Intro: Military Theater

By military theater I’m not talking about the elaborate musical theater shows that were commissioned by the U.S. military during WWII.

These shows were called Blueprint Specials—I saw excerpts that were restaged recently at the Intrepid Museum. Topflight Broadway talent was recruited to create “blueprints” for shows that any remote base could produce and stage. DIY musicals. The music, the script and the choreography were sent out as packages. Sets were simple and the costumes were the soldiers’ existing uniforms.

I’m also not talking about the use of the word theater as reference to an area of conflict and geographic operations—the North African Theater or the Pacific Theater in WWII for example—though the use of the word in that context might be unintentionally and oddly revealing.

I’m thinking about the idea that much military action is not done to achieve its stated purpose, but is rather, in effect, a show, staged for an audience. That audience might be us, the country on whose behalf the military has presumably acted, but the intended audience might also be a foreign country. The most famous and possibly most devastating, callous and horrific example of the latter might be the atomic bombs that were dropped on Hiroshima and Nagasaki. Not everyone will agree with this analysis, but the narrative we were taught in school was that this use of “shock and awe” forced the stunned Japanese to lose their will to continue fighting, and hastened their surrender.

There may be some truth to that. But others claim the Japanese were already on the verge of surrender. Their cities had been extensively firebombed and they were losing ground elsewhere. It is claimed that dropping atomic weapons on Japanese cities was instead a theatrical act. A show whose intended audience was the Russians, especially Stalin, whose influence and power were seen as a threat. It was essentially a “show” that said “look what we have and what it can do!”, with the implication being “don’t get too ambitious with your spheres of influence!”

One could similarly argue that many terrorist actions are effective more as theatrical gestures than as a means to achieve any military or political objectives. The horrific bombings that are often directed against civilians—9/11 and the recent bombings in Manchester and Afghanistan—have no useful military ends. The targets are often not military or infrastructure. They don’t capture territory. They are horror “shows” staged to terrify and the populace and media are the audience.

If one were thinking in conventional military terms, one might take out military bases, rail lines, ports, communications and infrastructure. Clearly this is not the aim with these actions. The aim, as in any performance, was to make an impression on the minds and hearts of the audience. We are that audience.

In the very recent London attack—where a small group of men drove a van into innocent civilians and then stabbed people with off-the-shelf ceramic kitchen knives—their theatrical gesture extended to wearing fake suicide vests as costumes. The vests were made out of duct tape and water bottles; designed to instill a theatrical fear effect, not to actually accomplish a military end.

We do the same thing.

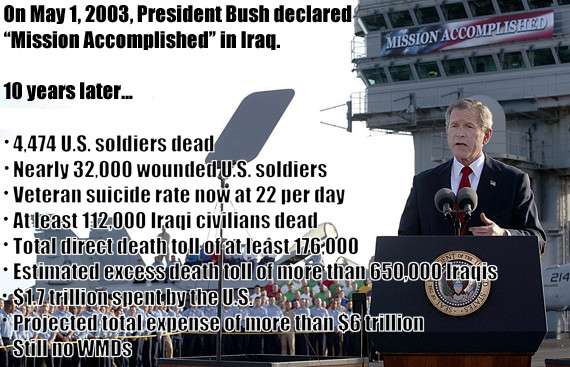

I have read statistics on the “surgical” bombing when the Iraq invasion began in 2003—not a single missile hit its target! Not one. (They must have hit something! If they landed in neighborhoods and killed civilians or destroyed their homes, then they likely became recruiting devices for the insurgency.)

Shock and awe?

Did that TV spectacle do its job? As rallying theater maybe, but militarily it was pure show.

Some recent military actions by the U.S. seem to continue this kind of “performance”.

President Trump recently ordered a bombing raid in Syria, ostensibly to make a show of response for Assad’s illegal use of chemical weapons. Tomahawk missiles were used to attack a Syrian government airfield. Upon investigation, this was revealed to be more about achieving theatrical rather than military objectives.

My friend Lucas Haarmann did some digging and sent me this:

LH: In this article

... it is pointed out that the Tomahawk missile is not designed to take out fortified air bases like the one in Shayrat. In Libya and in previous conflicts, the American military has always used much more powerful bombs dropped by warplanes to destroy runways and hangars - and if the intention was really to prevent Assad from carrying out further airstrikes, the US has highly capable aircraft that could carry out that mission with little risk. Furthermore, the Russians (and therefore probably the Syrians as well) were warned about the attack before it took place so most of the high-value materials and aircraft were probably moved out of the way. The use of the missiles was purely a symbolic gesture that arguably endangers the US intervention in Syria - the attack has broken a tacit agreement between Assad and the US not to attack each other and now American planes and special forces could face a retaliation from the Syrian army.

The only thing those 59 Tomahawks ($2 million each) achieved was a boost in Raytheon stock. Most of the missiles were reportedly shot down by Russian-supplied air defenses and the base resumed operations just hours after the attack because the runway itself was undamaged.

A huge waste of resources and lives….

DB: But as theater the U.S. audience and many of the pundits gave it a thumbs up.

The theatrical objective of this script was that Trump can be viewed as having empathy, being decisive and bold. Mission accomplished.

This was followed by the use of a massive conventional bomb in Afghanistan, the Mother Of All Bombs (MOAB). The MOAB is yet more theater perpetrated on a country that, by themselves, can’t fight back. Afghanistan as stage.

LH: The MOAB is huge - 30 feet long, making it so big it has to be dropped out of the back of a cargo plane - but Russian state news claims that the Russian military has an even larger non-nuclear bomb. https://sputniknews.com/politics/201704141052646394-russia-thermobaric-bomb/

According to the official press release, (http://www.rs.nato.int/article/press-releases/u.s.-forces-target-destroy-isis-k-stronghold.html) the use of the MOAB was justified as it was the only bomb capable of clearing out such a large area of IEDs, bunkers and tunnels without risking the lives of Afghan and American troops (and without the obvious problems of using nuclear weapons). The military and the Afghan government claim that no civilians were killed, but some locals contest that.

The war in Afghanistan - which is far from over despite the US pulling out - had largely been forgotten until the use of the bomb. It's almost as if (this is entirely just speculation) the use of the MOAB was a ploy by someone within the Armed Forces to reinvigorate political and public interest in Afghanistan at a time when politicians are preoccupied by Iraq and Syria.

DB: In other words, it was a theatrical gesture.

LH: Air strikes alone can never win a war- and they only worsen the underlying problems in the Middle East by further feeding the cycle of anger, political instability and war. The US is even running out of ammunition despite spending billions on increasing stockpiles. (https://www.usnews.com/news/world/articles/2017-02-17/us-raiding-foreign-weapons-stockpiles-to-support-war-against-the-islamic-state-group)

That money would probably be better spent equipping and training US-backed forces (the Afghan and Iraqi governments and the YPG in Syria). I think that the more discreet US backing is, the better. Otherwise it looks like another western 'crusade'.

I doubt the efficacy of the US military's 'shock and awe' strategy. Maybe an overwhelming display of force works against a rational enemy, but against a fanatical enemy with nothing to lose it may just heighten the enemy's fervour. Such blitzkrieg-style air attacks were of course also used in Iraq in 2003 - and look at what the long term impact has been!

DB: It seems the show has opened to bad reviews from the local audience.

The Russians have recently enacted a staged international “battle of the tanks” show—the Tank Biathlon—where they pit their tanks to those of other countries in a public contest. 17 countries compete. The Russians have won first place in all categories each year.

These theatrical presentations have a powerful effect. Perception is reality, and we love a good story that will succinctly explain things to us. But not everyone views a show the same way.

The massive air attacks mentioned above, it could be argued, despite being amazing theater, also served as a recruiting effort for the insurgency, with fundamentalist groups that soon emerged in Iraq that weren’t there before the US invasion. Not having learned from Iraq, the same plan is being tried again. The number of bombs and missiles dropped against ISIS is increasing—March 2017 was the record, with 3,878 dropped according to that same Guardian article. Theatrical and perceptual shows, have real world repercussions.

One wonders how many other military gestures and actions were essentially theatrical in nature. The gruesome staged snapshots from Abu Ghraib prison—stills from a show enacted for a small appreciative audience. Proxy wars—in which global powers use local conflicts and actors to face off against each other, might be viewed as theater; a theater with the distant enemy superpower as intended audience. Vietnam—the domino theory being the “script” and justification the U.S. followed. Russia’s invasion of Crimea and Eastern Ukraine—primarily a show to boost Putin’s ratings?

The cyberwars? Do the actors in cyber attacks actually want to get found out? A little country like North Korea causing widespread cyber damage—that’s a show that might actually play better than their missile test shows. Maybe, despite their denials, the Russians are happy that their meddling in Western elections is accepted as fact.

Do the actors in these dramas have a sense they are playing roles? Or is it method acting, and they are so immersed in their parts and deep in the script that they cannot see beyond the proscenium? I think in many cases the latter. As are we all.

All the world’s a stage

Here’s some dialogue from the movie The Man Who Shot Liberty Valance when it is discovered things didn’t happen exactly the way folks were led to believe:

Ransom Stoddard: You're not going to use the story, Mr. Scott?

Maxwell Scott: No, sir. This is the West, sir. When the legend becomes fact, print the legend.

We live in a world of such theatrical performances. I ran across the phrase “security theater” some years ago to describe what we all go through at airports. The immersive theater that involves the removal of shoes, belts and laptops (but not tablets?—ah yes, laptops it was discovered can be packed with explosives)... many of these procedures are a show designed to give us the feeling that the government cares about us.

Of course politics is a form of theater—

Trump pulling out of the Paris Climate Accords has no rational explanation, but it plays well to a shrinking but appreciative audience.

His advisor, the legendary and notorious Roger Stone is a master of these gestures. He did the same as advisor for Nixon and Reagan. He proudly acknowledges that it’s theater: “Politics is show business for ugly people.” (The recent doc Get me Roger Stone is jaw-dropping.) He makes it clear that even if something is clearly and obviously a staged fiction, even if the world knows this, it doesn’t matter—fiction well told is often more powerful than fact. Print the legend.

The Macron handshake—when French President Emmanuel Macron used a boldly theatrical gesture to show he would not be dominated by Trump. One assumes the intended audience was the French people who just elected him. Whether squeezing Trumps hand in a weird and uncomfortable manner really means the French will stand up to all sorts of U.S. interests is a good question—the handshake may not answer it, but it makes the theatrical intention clear.

All of this makes one wonder if, given a convincing role, a robust script and our susceptibility to these scenarios, any of us can make accurate judgements about what is going on? In the case of day-to-day and maybe even security theater, one might argue: if it makes you feel better, or feel somewhat more relaxed and safer, then why not enjoy the show? No serious harm done, right?

Do we really want to pull back the curtain? Or would we rather take the blue pill and stay in the play? I have a sense that the attraction to “narrative” is a bias we all share. Like confirmation bias and many others, narrative bias predisposes us to story explanations, and the simpler the story the better. Nuance, characters that are both good and bad, for example, are complicated. But we prefer our characters to be clearly good or evil, the choices to be black and white. If a narrative explanation works, if it explains a situation or action most of the time, then it becomes a shortcut to “understanding. No more mental effort is needed, and like the other biases, it adds to our amazing mental efficiency.

With politics and military action, where our futures and our lives are at stake, not to mention those of others around the world, it would seem the consequences of these theatrical seductions requires us to at least try and be aware that we are being seduced. With entertainment and the arts, I have found that one can be aware of the sleight of hand employed on stage and yet still be helpless to their effects. We can be moved and derive enjoyment even when we know the ending or when we are aware how the tricks are done. It doesn’t ruin the enjoyment; there is no harm in knowing. One doesn’t rush on stage and tackle the magician as he begins to saw the woman in half, but we still can enjoy being fooled.