GUNS ARE ABOUT FREEDOM: OUR FREEDOM TO LIVE

| June 22, 2016

It’s not hopeless.

No matter what some of my friends seem to imply, I firmly believe we can have gun control and reduce gun violence in this country. Allow me to be optimistic. At this point, any cause for hope is worth considering.

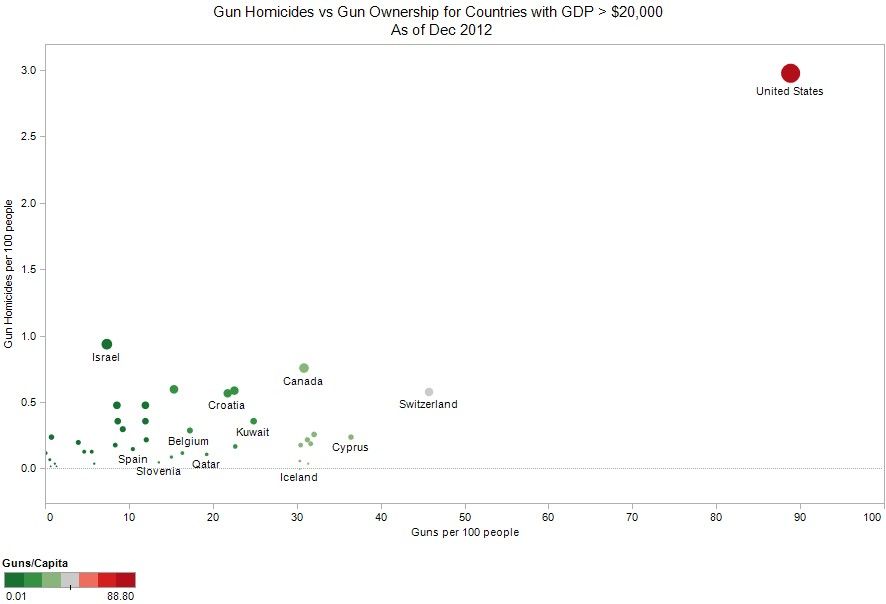

First off, I guess I have to be clear that I am for gun control. I believe the situation in the U.S. is unacceptable; more controls are necessary, and there is proof that they can work. Just look at the data. There is a staggering split in U.S. gun deaths and gun deaths in a host of other countries, as a New York Times report recently found. This is not news, but it bears repeating. They note that being killed by a gun in Germany is as common as being killed by a falling object in the U.S. Yet the results are pretty much the same, as the graph below from KD Nuggets shows:

We are at war here. Just look at those numbers. How could you conclude anything other than that we Americans are living in a war zone? More people die of violent gun related deaths in Chicago than American soldiers in Afghanistan, a sad fact that has given the Second City an unfortunate nickname—one that inspired Spike Lee’s latest film. And just days after the rampage in Orlando, a columnist for the Philadelphia Daily News bought an assault weapon in 7 minutes.

Some of the recent reaction to Orlando was about urging peace, love and toleration, and though that might help, everyone gets mad sometimes. If a conflict can be too easily resolved—whether in a fit of rage or mental instability—by firearms, then our current situation becomes inevitable. The temptation is too great, our self control is limited… errors, mistakes, and stupidity happen. Just consider all the children shot by their parents' unsecured weapons.

We are so far out of line compared to every other developed (and most of the not developed) nations that outsiders look at us and wonder what kind of crazy savages we must be. Most other countries have strict bans on assault weapons, with heavy restrictions on other weapons, as well. Some, like the U.S., still maintain hunting cultures that allow guns for “sport,” like Canada, Britain, and Austria, where nearly half of households own a rifle and one in three have a shotgun. Even so, gun violence in those countries remains low. Only a few hundred Austrians die from firearms each year, at a rate of 2 to 3 per 100,000 residents. That is compared to America, where the number is more than 33,000, or nearly 11 out of every 100,000. Never mind the fact we have fewer guns per capita, with about 20 percent of households owning a rifle or shotgun.

As the Austrian experience shows, it’s not about taking away everyone’s guns. It needn’t be all or nothing, in other words.

What's the Matter with America?

The question that gets brought up over and over—between my friends and I and so many others every time there is another massacre like the one in Orlando—is why can’t the U.S. be like these other countries? If they are free of this madness, why can’t we be?

People sadly shake their heads and say the N.R.A. is just too powerful. The group, its members and backers, cleverly threaten any politician who disagrees with their position, and they have successfully framed the debate to be about 2nd Amendment rights—about government interference in the choices of individuals.

It’s true the N.R.A. is almost as conniving as they are influential, and it’s true that most of our elected representatives are cowards who don’t represent the will of the people. After Sandy Hook, support for gun control grew 15 percent, with 92 percent of Americans wanting stronger background checks, according to a USA Today/Gallup poll that December. But 74 percent still opposed banning handguns while 51 percent still thought assault weapons should remain legal. Obama gave a speech berating Congress, but they still continue to do nothing.

They could have at least respected the wishes of the people and instigated stronger background checks. But no. As I type this in the late hours on Monday, just a few minutes ago all but one Senate Republican (and three Democrats) voted no on requiring background checks on all gun sales.

Still, others have recently suggested some ideas that give me hope — hope that this situation can change. And some books I’ve recently read (especially The Honor Code by Kwame Anthony Appiah) explore how similar, seemingly intractable practices, behavior, and ideas have changed in the past. That change happens when there is a broad consensus. But how does that happen? It happens when a practice and an argument are viewed from a different point of view.

Here I think is the key: Reframing the argument. Guns are primarily a public health hazard—now we have to start viewing, and treating, them as such.

Not only that, but for all the freedoms gun ownership supposedly entails, countless other freedoms have been curtailed—at schools, on university campuses, movie theaters, housing projects, nightclubs, bedrooms, and city streets. Nowhere is safe. This is a public health issue just like the dangers posed by driving, smoking, vaccinations, obesity and poverty.

And yet, banning assault weapons, which no doubt should happen, would not have as great an effect, nor save as many lives, as background checks and other policies. My own reaction, and I expect the gut reaction of many people, would have been to focus on assault rifles as those are what were used at Sandy Hook, Orlando, Roseburg, Oregon, and so many other mass shootings.

But Nicole Hockley, one of the mothers whose child was killed at Sandy Hook and who has become active in this area looked at the data and realized that although her own child died from an assault rifle, focusing primarily on those might not be the most effective way to save the most lives. After all, shotguns and handguns kill more Americans each year than rifles, and assault rifles in particular. And, Hockley discovered, background checks and other policies might be more likely to get passed, as revealed in the public consensus after Sandy Hook.

A Matter of Public Health

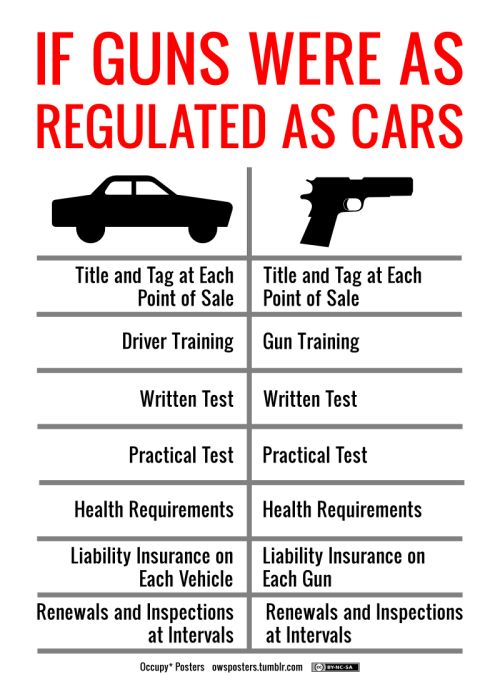

Yet there is another piece of deadly machinery we treat far more seriously than guns...

We willingly give up our rights in many areas—and we have come to accept what we get in return: a safer healthier life for all is worth the small prices we pay for it. People argued against the mandatory use of seat belts, and I suspect there are folks whose grandparents still sit on their seat belts in protest claiming, “The government can’t tell me what to do!” But most of us accept that the huge number of lives, medical expenses, productivity loss, and pain and suffering saved is a benefit not just to those involved in random accidents, but to everyone. We have come to realize that in some situations we all benefit by giving up some choice. We likewise accept that drivers need to be tested—for their driving abilities and competency—and we all feel safer on the roads as a result.

Cigarettes, large sugary drinks and fossil fuels have all had powerful lobbies behind them, and yet we have come to feel that the benefits of regulation in these areas often outweighs the rights of individuals to impose risk on others—which is exactly what guns do.

Appiah and others point out that we can and do change. Slavery was once broadly accepted, and now no one believes that any more. In just my lifetime, we have almost entirely rejected the notion that black people are inferior—a ridiculous, even offensive, idea today. And most folks now believe that gay people should have the same rights as straight folks,she shift that has largely taken place in a matter of years. These are huge changes, and some of them were unimaginable not so very long ago. There is hope.

How do these changes happen?

In Australia, where there is a strong gun culture, there was a massacre involving semi-automatic weapons in Port Arthur in 1996. For them, that was the tipping point. The public sentiment was already close, but that massacre in which 35 people were killed allowed them to act. The government leda massive collection and buyback program, and the effect was profound. Many studies have since verified the positive effect of this legislation.

Of course there were doubters, and the effects of the ban on some weapons were questioned. But repeated research over the years has proved that the change in policy saved a huge number of lives and granted Australians many of the freedoms that they cherish.

Other countries never had assault weapons available to the public, and some had no guns at all except for those for hunting. For them, the issue of what do we do with all that weaponry was never an issue. But Australia’s experience shows that even that thorny question can be dealt with, too.

The change needn’t be all top-down. Small groups who engage individuals have an inordinate effect. Change happens as new views, new thoughts, and new opinions on an old issue accumulate. The law that ratifies this new way of thinking may need to be enforced top-down, but the acceptance of a new idea comes from a broad consensus.

I think reframing the gun issue as a public health issue—as well as an issue of our right, and our freedom, to live without a constant threat of violence—is the way to go in convincing our lawmakers, and more crucially our neighbors and our nation, to act on this issue. The public feeling is already there: Everyone should not have the right to risk everyone else's life and take away the freedom of others.

We have countered these arguments before, from slavery to seat belts to smoking, and we can do it again. We’re better than this.