Saks 5th Avenue was getting a facelift, and would be covered in scaffolding for about 6 months. Through Jean-Yves Noblet of Pace Editions they offered a few artists the opportunity to create pieces on the scaffolding, covering the whole 5th Ave side above the sidewalk. 215 feet by 15 feet. That’s a big thing.

I realized after visiting the site that it would only be seen from either across the street or from cabs moving haltingly down 5th Ave. So, it had to be something you got quickly, like a billboard. I decided to make a kind of flow chart that connected the designers whose products are sold inside and various cultural effluvia in the world outside — the designers' influences, maybe, maybe not. I did it in the graphic style similar to contemporary ads, which made some pedestrians think it was an ad...but there was no tag line.

I have been working for some time on pieces that take off on the graphic family tree form of showing antecedents, ancestors and offspring… and in these pieces I often expand on this form to include all sorts of things — philosophical, cultural and personal — that might, in my world, be connected. They might be connected in your world, too.

It was natural to take this means of presenting information and stretch it horizontally — in order to elucidate the roots, the offspring, the infuences and the illegitimate children of some well-known fashion designers — for a public art piece that has to be apprehended quickly this form seems perfect. Everything really is connected — and while some of these connections may be obvious (you be the judge) others, though less known and possible suspect, are equally true. In fact all things are equally true, but that is another piece.

It was done fast, and whatever permissions were needed were speeded through — in a slower world I’m sure someone would have been worried that Donna Karan may not have liked being connected to Karl Marx, or Calvin Klein to Minimalism, but up it went and there were no lawsuits.

DB

A dense stream of tourists, workers on lunch break, and mid-day, mid-town traffic moved sluggishly through the area between Rockefeller Center and Saks 5th Avenue one recent broiling afternoon. Some paused to gaze at an unusual sight in front of Saks: a block-long banner with a flow-chart of words and phrases, including fashion designers and, well, other things—all set against a backdrop of clouds and bright blue sky.

“I see ‘Lite FM’, that’s a radio station, ‘Calvin Klein’, ‘hardwood floors’…I think it’s advertising,” said Alfredo Busanet, an employee of Rockefeller Center. Several passing tourists agreed that the words represented merchandise sold in Saks—including, presumably, ‘heartbreak’ (linked by arrows to ‘hangnails’ and ‘Bulgari’) and ‘radical utopias’ (between ‘beach culture’ and ‘Issey Miyake’.)

Others took a broader view. “We see it every day,” said Alberto Alamo, on break from his retail job with co-worker Dave Feliciano. The two young men, both lanky and agreeable-looking, were standing in the shade of a building across Fifth Avenue from the banner. So, what did they think it was? “I guess it’s like a thing of everything that’s related to this whole avenue, you know?” said Alberto expansively. “You have all these different brands which are sold on this avenue and in this neighborhood, but then farther up you have the museums that deal with some of the issues—the Guggenheim had something on ‘Deconstructivism’, and meanwhile the Met has something on ‘Karl Marx’, so it’s all related. But it’s also I think a description of the city itself, because it deals with all these different issues and all these different people.” “It’s a definition of us,” Dave added. “Like, that represents all of us, right now.” “Yeah,” agreed Alberto, gesturing towards Saks. “I mean, lookadat—‘rap lyrics’…‘sexual innuendo’…‘abstract art’! ‘Prenuptials’, that’s an everyday thing nowadays, you know.”

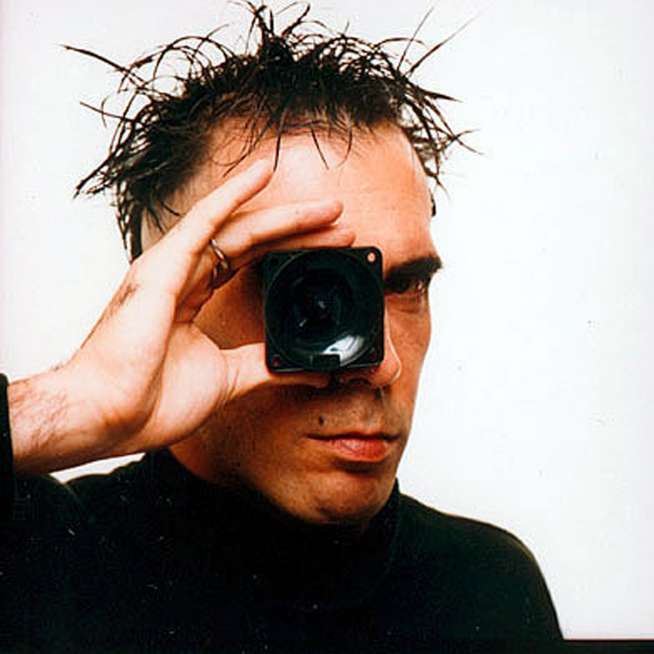

Indeed, “Everything is Connected” is the title of the piece, which was commissioned for Saks’ “Project Art”. The artist, David Byrne, has also (among his many and varied endeavors) created public art installations in Valencia, Sydney, New York, Belfast, San Francisco, Toronto, Stockholm and Tokyo. Following the installation of the Saks banner, Byrne waded into Fifth Avenue traffic to take a few pictures; then he pulled a white jumpsuit from his backpack, put it on and clambered into a cherrypicker to sign his name on the banner in dripping red paint. (When he was done, several Saks employees rode in the cherrypicker, too.) “It looks just like it did on the computer monitor—only much bigger!” he remarked, seeming surprised and pleased at the way things turned out.

The project was not without its complications, however. After production was already underway, Saks declared that one of the items in the diagram, ‘white trash’, was unacceptable. Byrne suggested a replacement—‘phone sex’—and when Saks (one might say predictably) rejected ‘phone sex’ he proposed ‘nihilism’, which was approved, to everyone’s enormous relief. Nevertheless, after the printers completed the 215-foot-long vinyl piece Saks reversed itself yet again: either ‘white trash’ or ‘phone sex’ would be tolerable, they said, but absolutely no nihilism!

Say what? Why would negation-philosophy be so abhorrent to a department store? Maybe they felt that either classism (it is Saks) or sex (which always helps sales) would be preferable to moral subjectivity, which can’t be said to help anything. Even so, is nihilism really more threatening than, say, the pairing of ‘Donna Karan’ and ‘Karl Marx’, or ‘Burberry’ and ‘rap lyrics’? Maybe—and this is just a guess—maybe someone pointed out that Nihilism was a revolutionary nineteenth-century Russian political movement which endorsed, well, terrorism.

Byrne, reached by phone in Belgrade during a recent stop on his “Lazy Eyeball” concert tour, noted that the word’s historical meaning hadn’t informed his decision and added that he still preferred his first choice and hoped it could be restored. But the hastily-produced ‘white trash’ replacement panel was for some reason never installed, so ‘nihilism’—somewhere between ‘Theory’ (the fashion brand) and ‘Reality Television’—has overlooked the teeming humanity at Fifth Avenue and Rockefeller Center. What, then, is the lesson of this story—or is there a moral center here at all? Perhaps it is just as Alberto and Dave explained: this piece represents the world we live in, including the slippery intersections between art, commerce, politics and language. We will just have to try to figure out the connections ourselves.

"It's Like a Thing of Everything..." Danielle Spencer, June 2002