One of the Glasgow musicians — Barry, the keyboard player from the group Mogwai — told a story about a guy he knows, a young singer songwriter. "All his friends are junkies. But he's nae a junkie. But he gives them stuff so they can get their drugs. Once he didn't leave the flat for a month because he hadnae any shoes. He lives in some council houses. He's got stab wounds all over his tummy." "Did he wear a shirt with the wrong color?" asked Una, the bass player. "No, it's just a bad area and he's got long hair."

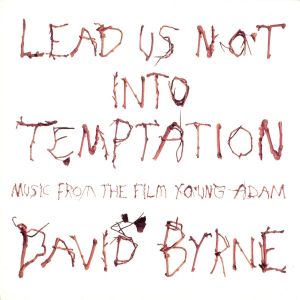

I was approached regarding scoring the film Young Adam by my friends Hercules and Jeremy at the Recorded Picture company. I hadn’t worked on a film they’d produced since The Last Emperor,though we'd kept in touch.

They said it was an adaption of a book written by a Scottish Beat writer. I was intrigued — I didn't even know there was such a thing as a Scottish Beat movement, but why shouldn't there be? I read the Alexander Trocci book and was tempted further — it smelled like a sleazier version of Camus' The Stranger, set in a colder climate. Trocci, it turned out, was a legendary character who sowed addiction and destruction wherever he went- from Glasgow to LA. I suspect he himself could be the subject of another movie.

Being Scottish myself, though long distanced from those roots, the fact that the cast and the director were all Scots seemed to tie the project completely to that place. When I talked to the director David McKenzie about appropriate sounds and moods we both wondered why bands such as Mogwai and Godspeed You Black Emperor hadn't be tapped for film scores — as their sounds are so cinematic. McKenzie then played me some cuts by contemporary Glasgow bands and I almost immediately suggested that rather than me use a bunch of NY or London players I could work with Glasgow musicians. I might then capture the weird tentative vibe that seemed to be emanating from a town that was in the midst of a kind of cultural revival while "drinking to throw up" as one friend described the aim of Glasgow imbibing.

I listened to a selection of records, many of them suggested by McKenzie, assuming that that in his choices he would gravitate to the mood he was after in his film, and from those I selected a group of musicians that I wanted to approach about this project. I told them I'd write some stuff in NY using samplers and such, mainly to have a framework to work form — to capture a vibe on specific scenes, and then the musicians and I would build on those ideas.

It went well — the musicians captured the right combinations of dark moods, sadness and sex. There were some amusing moments — had a hurdy gurdy player in — whose instrument was broken — only the drone string played (FYI a hurdy gurdy is NOT a little organ with a monkey attached, it's an old mechanical string instrument) — you crank a wheel and it "bows" both a drone string and melody strings which are played by depressing little buttons — it's an old instrument for fairground non-musicians. Anyway — I marveled at the fact that I was paying this guy, a skinny beaked nerdy Scot — to play his almost completely dysfunctional instrument. But the dysfuctionality worked in our favor... the one note, when tuned, was perfect — slightly scratchy and repetitive, but somehow not like an electronic repetition — sexier and more ominous.

I instructed him and the others in a kind of John Cagian indeterminacy — a you-pick-your-note system. I handed out bits of paper for specific scenes and said, "Here are the notes you can play on this scene- you can play them, and play them whenever you want in whatever order you want" ...in some cases there were two or more sets of notes that would be chosen in certain sections but for some cues there would be only a set of notes for the cellist and the accordion player to choose from (the hurdy gurdy guy had no options due to his malfunctioning instrument.) It sounded wonderful — drone-y but constantly changing and subtly surprising. And remarkably easy. I said to the engineer, "We could churn out a pretty good ambient record in a few hours like this."

[Later a friend mentioned that this technique was actually more reminiscent pieces by the late composer Giacinto Scelsi, who I hadn't heard of. They were right, his pieces Hymnos and Pax are both more or less one chord, often one note — his versions use sizable orchestras though, so the effect is different.]

I had a good time, it was nice to spend some time in Glasgow — I saw some family — cousins and nephews — and managed to work the names of the areas I'd pass by on the way to the studio into the song at the end — Sauchiehall Street and Kelvingrove Park. The Great Western Road is the thoroughfare that follows the River Clyde west to the former shipyards in Dumbarton, where I was born.

As is often the case, much of this music is not actually heard in the film — so this record represents another film, one with even less dialogue and a lot more music.

—DB