CONTENT DICTATES FORM

| February 19, 2014

I’ve been reading Stephen Sondheim’s Finishing the Hat (book 1 of 2) about how and why he wrote lyrics for so many musicals. I’m not familiar with most of these shows he worked on (if ever a book cried out for an electronic version with song snippets, this is it—speaking of content dictating form!), but it’s enlightening anyway. As he says, you can love to read cookbooks even if you don’t cook—if they’re well written you can apply the insights to whatever it is you do.

In the introduction, he invokes the above rule and a few others. Interestingly, a few of these rules seem to be borrowed from the guiding principals that modern architects were fond of claiming, but of course he applies them to writing lyrics. Applying the above dictate, for example, he suggests a writer first ask: (1) what it is that the song tries to say; (2) what sort of character sings the song; and (3) what other contingencies might the song need to address in the context of a specific show. These factors should dictate what you write, not some urge to be clever or to sound like what is currently popular.

For example, he talks about writing lyrics for West Side Story, which is a show I am somewhat familiar with. Sondheim says that although his collaborators pressed him to do otherwise, he believed that the characters in that show shouldn’t be singing in poetic metaphors that were too sophisticated or with overtly clever rhyme schemes—they were supposed to be kids from street gangs, after all. The guiding principals he mentions are pretty specific to musicals, but it’s not a stretch to apply them to any other kind of songwriting (I have to point out that musical theater, by nature, necessitates a bit of a suspension of reality; getting too nitpicky about what a real person would say, as in the West Side Story example, is a bit of a stretch.)

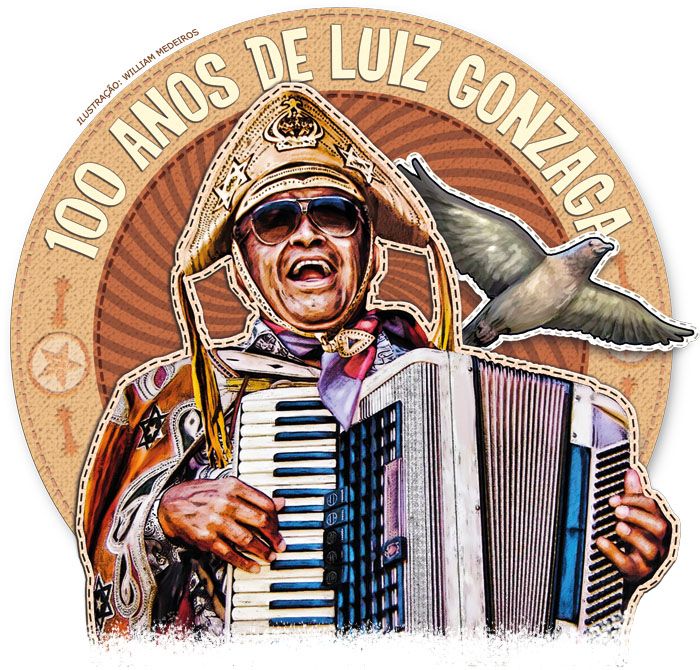

Applying this idea of writing for a specific voice and character in popular song, I’m reminded of Brazilian lyricist Humberto Teixeira, who wrote many of the words to the songs that the singer and songwriter Luiz Gonzaga made popular.

Gonzaga was a Brazilian singer famous for his songs about cowboys and ranchers and their lives in the hardscrabble Brazilian Northeast in the middle of the last century. He dressed the part; like our own Hank Williams and other traditional country singers, his outfits were an extreme version of a traditional Brazilian cowboy.

Teixeira was a sophisticate from Rio, but he instinctively knew the lyrics he was writing had to sound like Gonzaga could have written them himself. Their most famous collaboration was a song called “Asa Branca” (hence the bird flying over Gonzaga’s shoulder in this illustration). I did a version in English with Forro in the Dark, but here’s the original.

From there, I got to thinking about issues like song length and by implication, the shape of almost any creative form. Are we limiting our imaginations as far as musical and other forms go because of extra restrictions? I wondered if both length and shape might have been tailored not just by the contingencies of who was singing (if it’s a song) or who the characters are in a novel (usually characters in novels have internal monologues that are more or less identical to the way they talk), but also by whatever medium we might receive that creative form in.

Thinking about songs, I asked myself (as I have many times in the past) if the average 3-minute length has any reason for existence beyond the fact that that’s what could fit on the available piece of vinyl back in the day. A 78, about the size of an LP, held one song on each side, as did 45s…and a side would play three minutes of music at decent quality and volume. (I remember traveling in India in the '90s and you could still buy 78s, including Beatles 78s.)

Could it be that over the past 100 years we’ve come to believe that the length and form of what we call a song naturally falls around three minutes and has nothing to do with these recording mediums? Do we believe that’s the perfect length for what a song needs to do? Have we convinced ourselves that we as songwriters have gravitated to some archetypical shape and length that has reasons for existence and longevity beyond the needs of the contingencies of available technology and the marketplace? That the perfect 3-minute pop song length touches something biological within us partly because of that concise form? (“Stairway to Heaven” and “Hotel California” excepted.)

I think we might be deceiving ourselves there. Some “songs” indeed used to sometimes fall around the 3-minute mark (some old folk songs, sonnets and love songs) but many of the verse epics that have come down to us (Homer’s Odyssey, Ovid’s Metamorphoses; Beowulf and the Mahabharata) were all originally meant to be sung, or recited to a melody if you prefer. Those musical forms are long, long, long. The reason that they were subdivided into episodes with rhymes and stanzas, was because those are mnemonic devices: it’s easier to memorize long songs if the rhyme scheme is consistent and repetitive. Rhyming, itself, is a mnemonic device.

Semi self-contained episodes make a long work easier to recall as well. I sort of doubt the melodies in these epics varied a lot. I suspect that, like the rhyme schemes, the melodies were more like those in R Kelly’s epic Trapped In The Closet—not too convoluted. Maybe there was some melodic variation here and there for emphasis, but more than that would have made them unnecessarily complicated. As with Trapped In The Closet, one 3-minute chunk pulled out of one of these epic “songs” wouldn’t give a sense of the whole drama, comedy or whatever the piece was about. That makes me think that maybe our typical song form is pretty artificial—it may work perfectly to accommodate the time limitations of early vinyl recordings that were played on radio (plus the modular 3-minute chunks meant one could program plenty of space for advertisements). It also works in karaoke bars (harder to hog the mike) or for a scene in a musical—but there’s no reason all “songs” have to be that way.

Similarly, most books (both novels and non fiction) fall somewhere around 300-400 pages in physical form. I ask myself if that’s evolved to be the average length because that’s the best length for establishing sufficient depth of character, telling a rich story or expounding an argument (if it’s a non-fiction book), and if that’s why that length has become more or less ubiquitous. But look at the folk narrative forms: fairy tales and One Thousand and One Nights are mostly self-contained short stories, and they’re only a few pages long each. OK, the characters in those are simple cardboard cutouts, which it turns out is fine for that form. (Granted they have been packaged into book length collections, but the stories live independently of those collections.) One suspects that to fully identify with a character with depth in a novel or to expound a proposition (in non-fiction), maybe one does need more length than a typical blog post. But as with songs, how many of these restraints are artificial?

Movies used to be shorter—90 minutes at best—but now they tend to fall around two hours. But is that 90-120 minute length just an adaptation to the needs of cinemas to get a number of shows in a day? Is that what dictated that length? A lot of folks now watch TV shows that take way longer to develop their characters and stories. To watch a whole season in one sitting can take days. And people do it! It’s like watching an 8-hour cinematic movie, which no studio would ever agree to make. Charles Dickens, Mark Twain, Alexandre Dumas and Tom Wolfe wrote their big novels episodically for newspapers. The chapters were therefore necessarily short, and like TV shows, each chapter ended leaving you longing for the next installment.

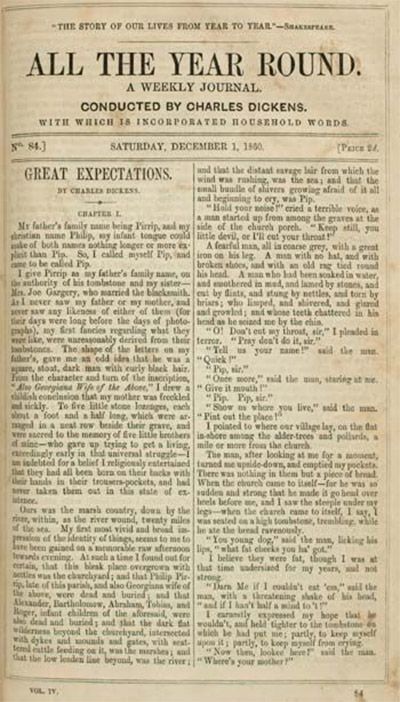

The first installment of Great Expectations was like this—each episode covered less than half of the front page of the newspaper!

What does the credit “Conducted By Charles Dickens” mean?

And what does “with which is incorporated household words” mean under that? Does that mean he’s not going to get all fancy on us?

Could contemporary novels work like this? Dribbled out in installments like those that Charles Dickens and others wrote? A chapter a week that is, for example, included as part of your Sunday paper. (That’s sort of how those big novels came into existence.) Or it could be more like an online magazine subscription: you’d find a new chapter on your device every week….much like a cable TV series. I gather there is suspicion that readers might be frustrated having to wait a week for each episode/chapter, but it might be a way in for folks who might be wary of committing to a long piece.

This installment model might encourage truly long-form work in various mediums: episodic novels, for example, whose length would stretch based a bit on their popularity...as many TV series do. Writing episodically would also mean—for better or worse—that the writer couldn’t go back and revise the first chapter—it would have been already released. Whatever quirks of character of plot might arise, well, the writer would just have to sort those out. The key might be to stick to an overall outline and don’t give in to the networks’ urgings to stretch the material.

A lot of non-fiction works this way already. Malcolm Gladwell’s books often began as separate magazine articles, which then were added to and collected to make a sort of thematically coherent book. Lots of other non-fiction books begin in similar ways: as TED talks, research papers or blog posts. Could I call this blog post a “book” and charge 10 cents for it?

I notice that magazine articles generally don’t get reviewed and promoted nearly as much as the same pieces when collected in book form. There are exceptions: Hiroshima and Seymour Hersh’s piece on Abu Ghraib in the New Yorker, Matt Taibbi’s “Goldman Sachs: Vampire Squid” piece in Rolling Stone as well as Tom Wolfe’s non-fiction pieces that were published there back in the day. But those are exceptions. Similarly, a single song released online might get a mention if it’s scandalous or has a must-see video attached, but a collection of 10 or more songs gets taken seriously. An album gets reviewed, marketed and advertised.

Similarly, the amount of press, promotion and marketing required to draw an audience’s attention to a short film (ones that haven’t gone viral anyway) is more or less the same amount of effort one would have to spend, in both money and time, on a feature. Given the desired difference in income that longer forms generate, creators and their backers are understandably inclined to the longer forms, where they might have a slim chance of making an income from their work. (But would folks toss 25 cents into a digital bucket to read a magazine-length piece? It might be less of a commitment and easier to try.) The other alternative for folks who want to make episodic short films or videos is to have one’s own series; one’s own channel, which YouTube allows. Google takes a healthy 40% chunk of the ad revenue from those, which one could understand if there was a physical copy involved, but at present that makes it pretty hard for creators to make a living and amass some savings.

There does seem to be an economy of scale.

Vocal music (songs or some new unimagined format) on the installment plan is a little hard to imagine. I can’t wrap my head around how that could work. But hey, how about this: what if songs were bundled with another medium—as with Dickens’ novels? Imagine, if when purchasing an episode of Grey’s Anatomy, for example, you got MP3s of the songs they used in the soundtrack. Not totally crazy. But that’s not stretching the form itself.

I ask myself if, is it simply that economy of scale that is leading us to be creatively conservative? Amazon is, I notice, trying to introduce “singles”—novellas or long form journalism—as is the app Atavist, which actually pays writers to create works in these forms that are not newspaper articles or full-length novels. There was a flurry of text message novels in Japan, but that seemed a bit of a gimmick. So there is some envelope stretching going on.

I had a music theater piece at the Public Theater last year (it will be back this spring!) and to some extent that experience both raised and answered some of my questions about songs and music formats. The audience was not there to hear a few hit songs, as they might at a concert, (not yet anyway, most hadn’t even heard the songs), so the songs were allowed to function on a level playing field, as a sequential whole. It took most of the 90 minute running time for the meaning of the songs to sink in, or at least I hope they sank in. It seemed to me that later songs in the piece had whatever impact they had because of what you’d heard and seen earlier. Most were still songs that fell around the 3-minute mark, but viewed as a whole it was a 90-minute piece.

I could easily see a hip-hop album working this way. It would seem more natural than what I was trying to do. It’s a perfect form for developing stories and exploring interactions between characters, all of which would play out over the length of an entire album….or even longer. Kate Tempest’s “Brand New Ancients” performance piece does this. Is that a contemporary musical equivalent of the Homeric epics (minus the gods and heroes)? Could that kind of sung epic verse happen again after a thousand years? I did see a music theater piece called “Life and Times” last year and the first two sections were entirely sung (and sometimes danced). The show was more than two hours of music, not quite broken into songs, though there were melodic high points and recitativo sections (those are the parts where the singers in operas sing tuneless dialogue scenes). It was wonderful—I recommend seeing parts 1 and 2 if they ever do it again.

I wonder how much these prejudices regarding form will change in the near future. I can certainly foresee that audiences are already drawn as much to episodic TV shows as they are to feature films. Maybe they will largely abandon 2-hour films altogether? One could imagine feature films being eventually relegated to a few IMAX spectacles and every other kind of film or video being on basic TV, cable or the Internet…and both longer and more episodic. That’s a major shift in form, and it might be happening really quickly.

A recent New Yorker article on Netflix confirms that new media has significantly affected change in both the viewing and creative experience of a show:

"Without commercial interruptions, Hastings argues, the viewing experience has become more immersive and sustained. Cindy Holland, Netflix’s vice-president of original content, told me that the average Netflix viewer watches two and a half episodes in one sitting. The creative experience is different, too, she said; making 'House of Cards' was akin to making “a thirteen-hour movie.” There was no need to recap previous episodes or to insert cliffhangers. Increasingly, show creators can work without executives’ notes, focus groups, concerns about ratings, and anxieties about whether advertisers will resist having their products slotted after a nude scene or one laced with obscenity."

As a reader, I personally consume more long-form essays and non-fiction articles than anything else. These often require a few sittings to complete, but I wouldn’t wish them to be shorter. I sometimes feel odd because I can’t tick off a lot of entire books I’ve read, which is kind of silly—that’s not really the point of reading. I wonder if there’s a reason those kinds of pieces haven’t gotten a life as independent items (most of them are in magazines or journals.) I know Amazon does what they call “singles,” but I sense that reviewers are loathe to write about something that is only available via Kindles, as it would be capitulating to Amazon’s dominance.

I have a feeling physical books might go the way of CDs, which are still around but now account for just 35% of record companies’ and artists’ income. I am concerned about the streaming/subscription model being proposed for books and journalism: as with music and movies, it doesn’t seem like it will generate enough income to support the creation of quality content- especially if it becomes ubiquitous. The subscription model might be a response to the decline of ad dollars in the digital world, but it doesn’t seem like a lasting solution.

But on the bright side: what kinds of fantastic and exciting new forms could emerge? Novels that never end? Albums that are essentially one track? (I think Prince and Eno both have tried this.) Pay-as-you-go blog posts? Songs that are like audiobooks, with hundreds of stanzas that take four hours to take in? Short-form TV series, with shows under 20 minutes in length? Videogames that tap into the data you generate, so that they tailor themselves to your likes and dislikes? Or maybe they will feature you as the protagonist, based on the cloud of data you trail and leave behind?

It seems the audiences are willing to adapt, but in many cases it is we the creative types who are being slow to create those new forms...to really create radically new forms to accommodate whatever content might be lurking. Granted, it’s hard to jump into a new form if there’s no hope of getting paid, and maybe there’s a lag in the evolution of financial models as well…but if any of that gets sorted out it could be exciting.