Cultural Spaces: No Separation of Art and Life

| May 8, 2018

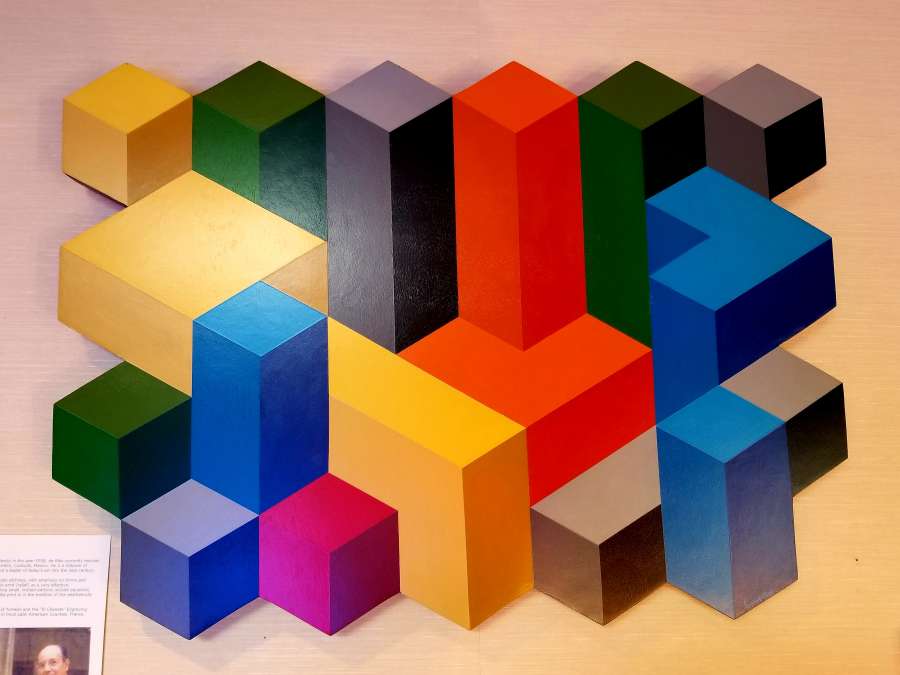

While I was in Dallas, I went to a strange and wonderful museum called the Museum of Geometric and MADI Art. Here’s a sample of the typical work on view:

Un Encuentro Difícil by Alonso de Alba Bessonnier, 2012.

In general, the work was not to my taste, but the museum itself was kind of wonderful in two ways: on the one hand, it presents an alternative artistic history that runs parallel to other, better-known narratives. And on the other, it eliminates the separation of art and life. It is a geometric art museum housed inside a working law office (those are shelves of law books on the left).

Apparently one of the partners of the law firm and his wife began collecting work from the MADI movement twelve years ago (a movement I’d never heard of). The couple were partially inspired by one Uruguayan artist, Carmelo Arden Quin, who was a protégé of the well-known Uruguayan artist Joaquín Torres-García (Torres-García I was familiar with, so the unfamiliar had a connection, a link, to the world I knew). Arden Quin moved around a bit, influenced others and co-wrote a manifesto that helped launch the MADI movement, which is an artistic style of geometric abstraction.

Lo and behold, as evidenced by all the examples on the walls, there were and continue to be other artists involved in this movement. They are located all over the world—in Venezuela, Slovenia, Japan, etc.—and have been churning this stuff out for decades. Some produce work a bit like Wassily Kandinsky, others make art like Victor Vasarely (using optical effects) and some are in a world all their own.

The museum’s wall labels generally include little black and white thumbnail pictures of the artists: a man standing on the street in Slovenia, a woman who looks for all the world like a Texas housewife and an Argentine artist whose posture seems to imply some local stature. The texts provide biographical details and, of course, the names of the works and when they were made. Some of us might be familiar with a few of the practitioners—like Vasarely—but almost all of the artists represented on the walls were completely unknown to me.

“How long has this been going on?” goes the song. I love hints of other, previously unseen universes that run parallel to the one I know and the idea that these universes may speak to one another from time to time. Just recently, while in San Antonio, I learned the Mexican American war was not about a simple land grab, as I had assumed, but was essentially about slavery. More on that in another post, but the point is, in one day my narrative had changed.

When I come across a new aspect of history or news of a cultural movement I wasn’t aware of, I realize suddenly that history might not be how I had assumed it was. Vast Amazonian kingdoms might have rivaled those of Mesoamerica or Egypt. I’m making this up, but it’s not implausible. It’s also not implausible that cultural and technological influences may have existed between distant continents. The whole story of humans, the narrative we were taught as children, continues to be rewritten. That the narrative of history is subject to change every so often is pleasantly disruptive and challenging. The past is not fixed—which means the present is not fixed either.

We construct narratives in order to explain aspects of the world to ourselves—whether scientific or cultural—and we like to think those paradigms and stories are set in place once we accept them. Move on, box ticked, this is how that is or this is why it happened that way. The whole idea of artistic “progress”, that art keeps improving, for example, has been attributed to the Italian artist and architect Giorgio Vasari. However, his encyclopedic series of biographies, Lives of the Most Excellent Painters, Sculptors, and Architects, focuses almost exclusively on artists from Tuscany (Florence) and Rome. El Greco called him stupid for refusing to recognize the significance of artists outside his own narrative universe. The whole “improving” narrative is therefore deeply suspect.

We all do this, construct these narratives, not just in art history, but in science, literature, you name it. They hold until something from outside our conceptual universe appears and challenges our preconceived storyline. Which leads to the question—what will we do then? Will we suppress this new information or will we revise our thinking?

When you consider surprising phenomena or developments that were previously ignored—the influence and contributions of women to historical progress, the Tropicália movement or this worldwide movement of geometric abstraction—you are, if you are willing, forced to revise your thinking and create a new narrative to include this new information.

Art and Life

Not only does the Museum of Geometric and MADI Art reveal the history of an often overlooked parallel art movement, but here, in this building, the border between the law offices that house this collection and the museum is porous. On the ground floor, most of the work is shown chock-a-block salon style, with as many pieces as possible jammed onto the walls. When I entered, I was met by a receptionist for the law offices. I was disoriented for a moment—she gestured toward the “museum” area and went back to her work.

I wandered about for a bit, taking in the various worldwide examples of this movement and reading the biographical labels. In the little bookstore, a man approached me and, here’s where it gets really interesting, he told me, “There's more upstairs,” and then, “But I have to let you in as there are offices up there.” So up I go, wandering amongst the law books and offices, interrupting meetings even.

I found this lack of separation between work and personal obsession inspiring. Most private collection museums leave the source of the money that supports the acquisitions and exhibitions a mystery. The collections are kept entirely separate from the business side of the collectors’ lives. But, in this case, the day-to-day work aspect of the collectors’ professional lives is right there in the open, intermingled with the artwork they love. The usual compartmentalization of aspects of one's life has been removed. Art and work, passionate interests and day-to-day business intermingle and presumably influence one another in some way.

Here is a different way of imagining how a cultural space or institution might be organized.